Originally published 2 February 1987

Here’s a quiz for you: Name all the women you can think of who made an important contribution to science before the year 1910.

If you named Marie Curie, award yourself three points out of a possible 10. If you named any other woman, give yourself the full 10 points.

My quiz is prompted by a new book called Women in Science: Antiquity through the Nineteenth Century, written by science historian Marilyn Bailey Ogilvie and published by the MIT Press. Ogilvie’s carefully-researched biographical dictionary contains information on 186 women scientists. It is a record that is striking because of its skimpiness.

I know something of the history of science, and especially the history of the physical sciences. Of the 186 women listed in Ogilvie’s book, I recognized the names of eight. One of them, Queen Christina of Sweden, was hardly a scientist, although a generous patron of the arts and sciences of the 17th century. Mary Somerville (1780 – 1872) was a brilliant expositor of the scientific ideas of others, best known for her lucid popularization of the celestial mechanics of the French physicist Laplace. Mary Anning (1799 – 1847) was an amateur fossil-hunter of Devonshire, Britain, who in the early years of the 19th century found the first complete skeleton of an ichthyosaur, a plesiosaur and a pterodactyl.

Four made mark in astronomy

Four others, Caroline Herschel, Maria Mitchell, Annie Jump Cannon, and Henrietta Leavitt, were astronomers. Caroline Herschel (1750 – 1848) was the sister of the great astronomer William Herschel. She began as his assistant and went on to make important discoveries of her own. Maria Mitchell (1818 – 1889) learned the science of the stars from her father on Nantucket Island. She discovered a comet in 1847, and for that achievement was elected the first female member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Annie Jump Cannon (1863 – 1941) and Henrietta Leavitt (1868 – 1921) were on the staff of the Harvard Observatory. Cannon’s career involved the observation, classification, and spectroscopic analysis of stars. Leavitt studied stars that vary in brightness.

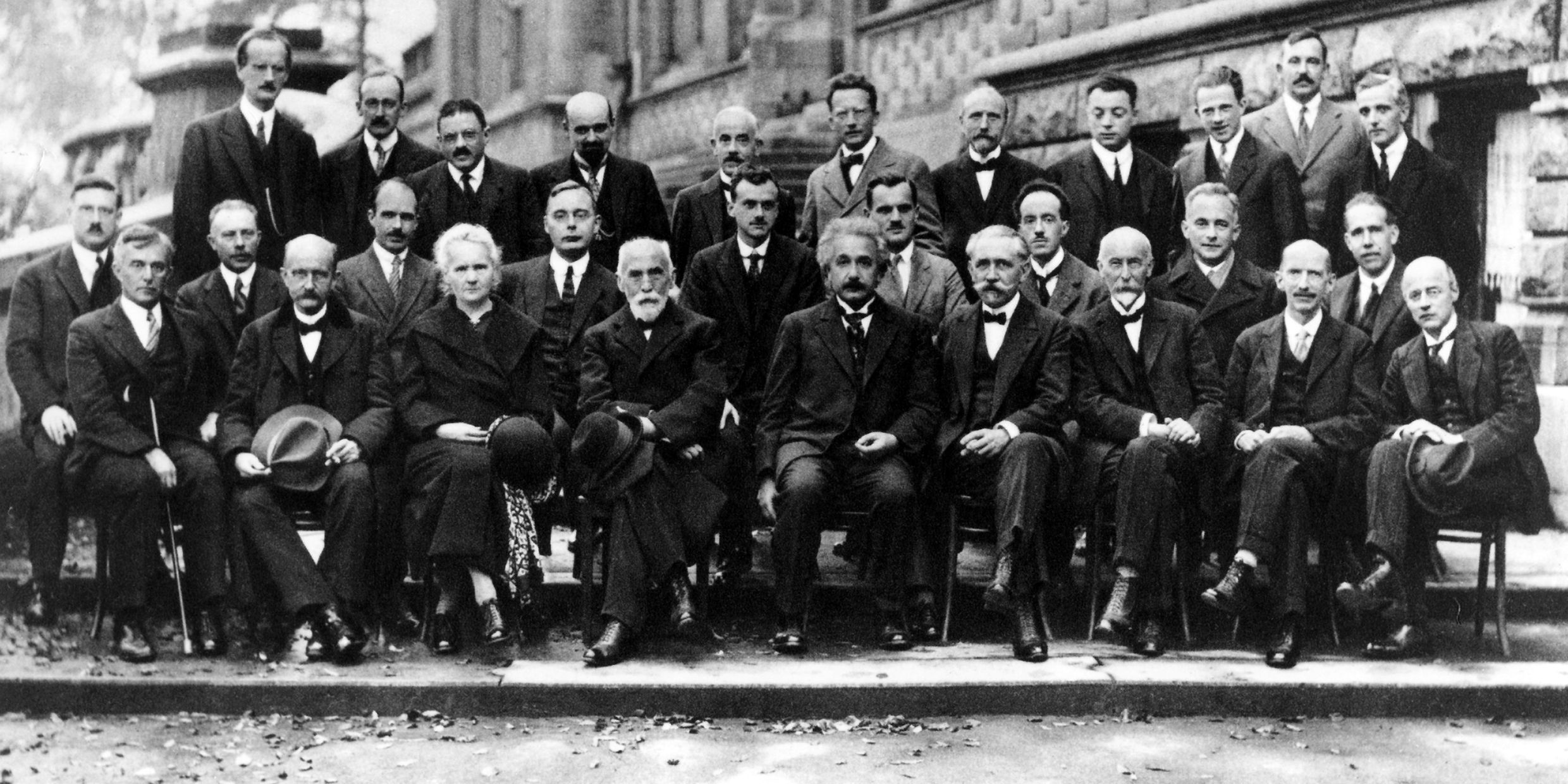

And of course, there is Polish physicist and chemist Marie Curie (1867 – 1934), who twice won the Nobel Prize for her investigations of radioactivity and the discovery of the elements radium and polonium.

The sum total of the contribution of women to science before our own century is not impressive. What are impressive are the cultural barriers that were required to be overcome if a woman was to make any contribution at all. Mary Somerville’s family thought her scientific activities an unwomanly pursuit that might damage her health. Even in the case of Marie Curie, male scientists were quick — too quick — to assume that the real creativity in her scientific work derived from her husband Pierre. The women struggled long and hard to be taken seriously by their families, friends, and male colleagues.

The nature of that struggle was clearly recognized by the astronomer Maria Mitchell. After her discovery of a comet, Mitchell went on to become professor of astronomy and director of the observatory at the newly founded Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. Her experiences with Vassar students convinced her that women had the ability to do first-rate science. More important than gender was education and expectation. In her later life, Mitchell became increasingly committed to the idea of higher education for women, and advocated the endowment of women’s colleges.

Unnecessary obstacles

Mitchell’s dream of gender-blind science has been long delayed. In physics, the worst case, women constitute only 3 percent of those holding doctorates, and only 1.5 percent of senior faculty positions in universities granting that degree. In the 1970s there was a dramatic rise in the number of women earning undergraduate degrees in science, but, except for computer science and medicine, that trend appears to have leveled off — at a level well below the proportion of women in the general population.

If women can do science, it is often asked, then where are the great female scientists? And why do women not achieve the same level of success as their male colleagues, as measured, say, by the number of professional publications? Perhaps hints to the answers to these questions can be found in a careful reading of Ogilvie’s book. What comes across is the great love of doing science that many women have shared with men. What is also apparent are the formidable barriers that have been thrown up against them.

Against almost insurmountable odds, women of earlier centuries struggled to do quality science, in isolation and without support. The situation has improved — doing science is no longer considered dangerous to a woman’s health. Women have won three Nobel prizes in medicine in the last 10 years, but there is still more progress required in order to achieve equality in science.