Originally published 4 July 1994

On the shelves of my college library, the biographies of Teilhard de Chardin rest between those of the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre and the mystic Simone Weil.

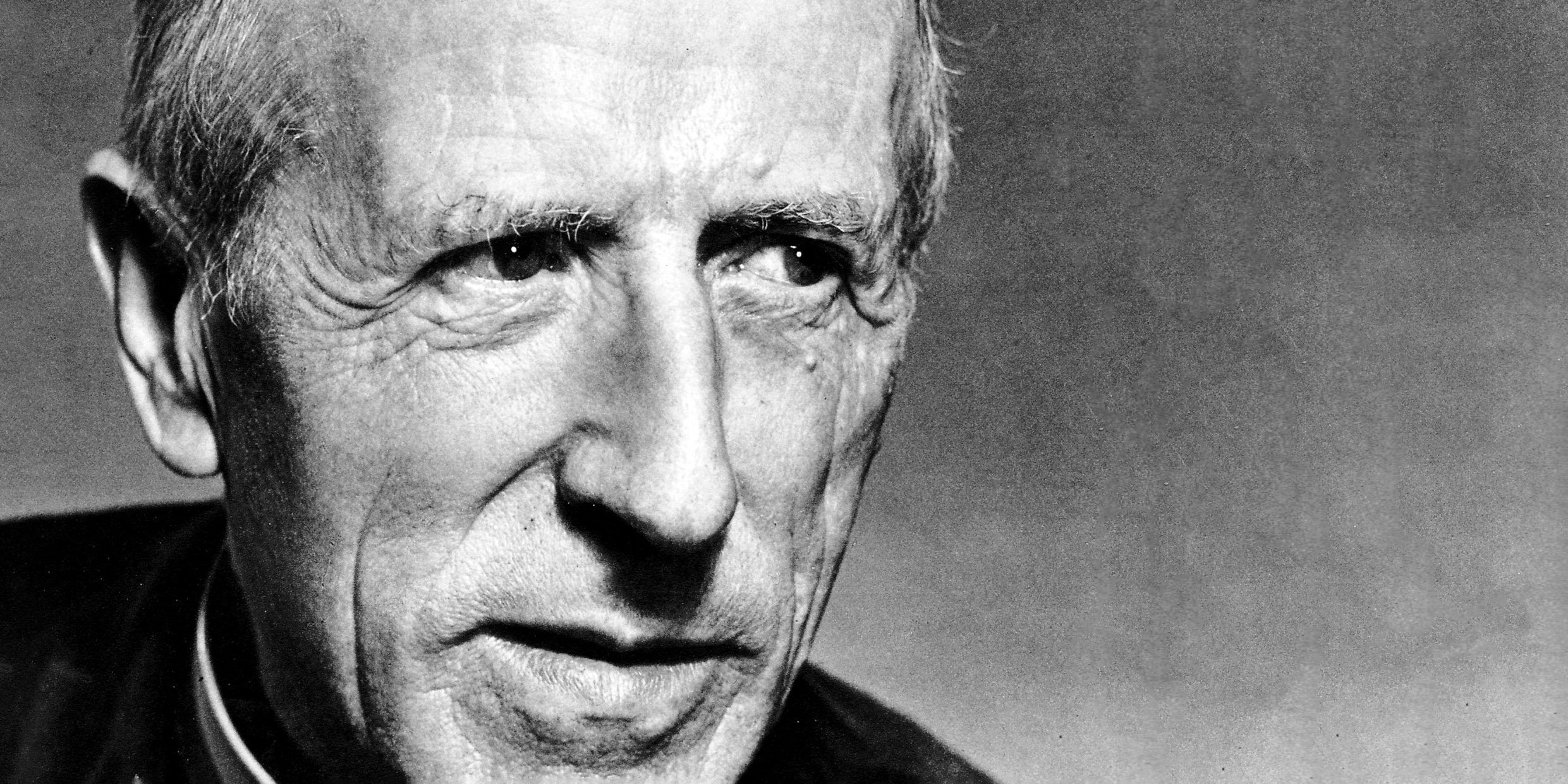

Teilhard was a Jesuit priest, a field paleontologist, a philosopher, and a mystic. He traveled the world to excavate the fossil remains of human ancestors. The concept of evolution was central to both his scientific and philosophical work. He looked for the completion of evolution in a kind of cosmic consciousness — the “Omega,” he called it — that he identified with God.

At the end of his life he was a man alone, lost in the chasm between 20th century science and medieval religion.

Teilhard shared with Sartre a close attention to existential phenomena, and with Weil a romantic religiosity and greatness of spirit. It would be nice to think that in some better world he is now enjoying a glass of wine and conversation with his two compatriots.

Teilhard’s best-known book, The Phenomenon of Man, appeared in English in 1959, at a time of spiritual crisis in my own life. I was studying physics at UCLA, and seeking to reconcile the religion of my past with the science of my present.

In science, I had discovered a universe of staggering complexity and beauty: vast reaches of space and time in which human existence shrank to apparent insignificance. The human-centered theology I learned as a child seemed narrowly inadequate. Nothing I had been taught in my religious education seemed capacious enough to encompass what I learned in science.

Teilhard de Chardin blew into my life like a breath of fresh air. He was a man who grounded his every thought and feeling in the facts of science, and yet who had a deeply religious vision of the universe.

The very first words of his book swept me into their thrall: “To push everything back into the past is equivalent to reducing it to its simplest elements. Traced as far as possible in the direction of their origins, the last fibers of the human aggregate are lost to view and are merged in our eyes with the very stuff of the universe.”

Stuff! The stuff of the universe. But not the dreary, geometrical atoms of the physicists. Rather, Teilhard’s “stuff” was mind-stuff: energetic, rich with emergent possibilities, and carried along by the swelling river of evolution from the Alpha of creation to the Omega of redemption.

His vision was like an hallucinogenic high, a jolt of electricity. It convinced me that religion and science might be reconciled after all.

Recently, after more than three decades, I picked up Teilhard’s book for another look. It is easy to see what exasperated his scientific colleagues, and finally exasperated me. Teilhard claims his book is to be read as science, but it is a tissue of intuition, and words — “noosphere,” “the cosmic law of complexity-consciousness,” “the Omega” — that have only the vaguest scientific usefulness.

The Phenomenon of Man was hopeless as a program for bridging the gulf between science and religion. It is far too mystical to appeal to scientists, and too pantheistic to satisfy theologians. It is the intensely personal confession of faith of a God-struck dreamer.

Yet, I will not fault Teilhard for trying, and much that is in his writings now strikes me as on the mark.

He looked for some force or principle, different from any yet articulated by science, that drives evolution towards complexity and consciousness. It seems to me that science is still grasping towards such a principle, and that the new mathematics of chaos and complexity may provide a first glimpse of what it might be.

He knew that the chasm between science and religion was central to our culture. He thought the Roman Catholic Church was deliberately starving itself to death out of its own antimaterialism, and that it could regain vitality for the future only by allying itself with the scientific quest for truth. “If only Rome would start to doubt herself at last, a little!” he wrote in a letter.

Finally, he saw that a reconciliation of science and religion demanded new formulations of religious truths, consistent with scientific knowledge of the cosmos, yet faithful to the past and embodying our deepest aspirations for worship. The Phenomenon of Man was his attempt to provide those formulations.

His mistake was to call what he was doing science, rather than theology.

Teilhard’s superiors in Rome knew the difference. They knew that his book was theology, and they forbade its publication during his lifetime. They were not prepared to admit the least doubt about medieval definitions of God and spirit. Teilhard himself was banished from his beloved Paris to the gulag of America.

He died in 1955, in exile, with much of his life’s work officially censored. Near the end of his life, he wrote: “How is it possible that I am so incapable of passing on to others…the vision of the marvelous unity in which I find myself immersed?”

The chasm he sought to bridge remains.