Originally published 17 September 2002

History is not the same old same old, nor is it just one darn thing after another. History — cosmic and human — has a direction, and the direction can be quantitatively defined.

Eric Chaisson, a physicist at Tufts University, defines cosmic evolution as an ever-increasing concentration of energy as it flows through space and time.

For example, vastly more energy flows through a star than through a worm, but the concentration of energy is greater for a worm than for a star — roughly 10,000 ergs per second per gram for a worm versus 2 ergs per second per gram for a typical star.

I’ll spare you the technical details, but when Chaisson calculates energy concentrations for everything from stars to cells to worms to human brains, he gets an exponentially rising curve that he takes to be the sign of increasing complexity.

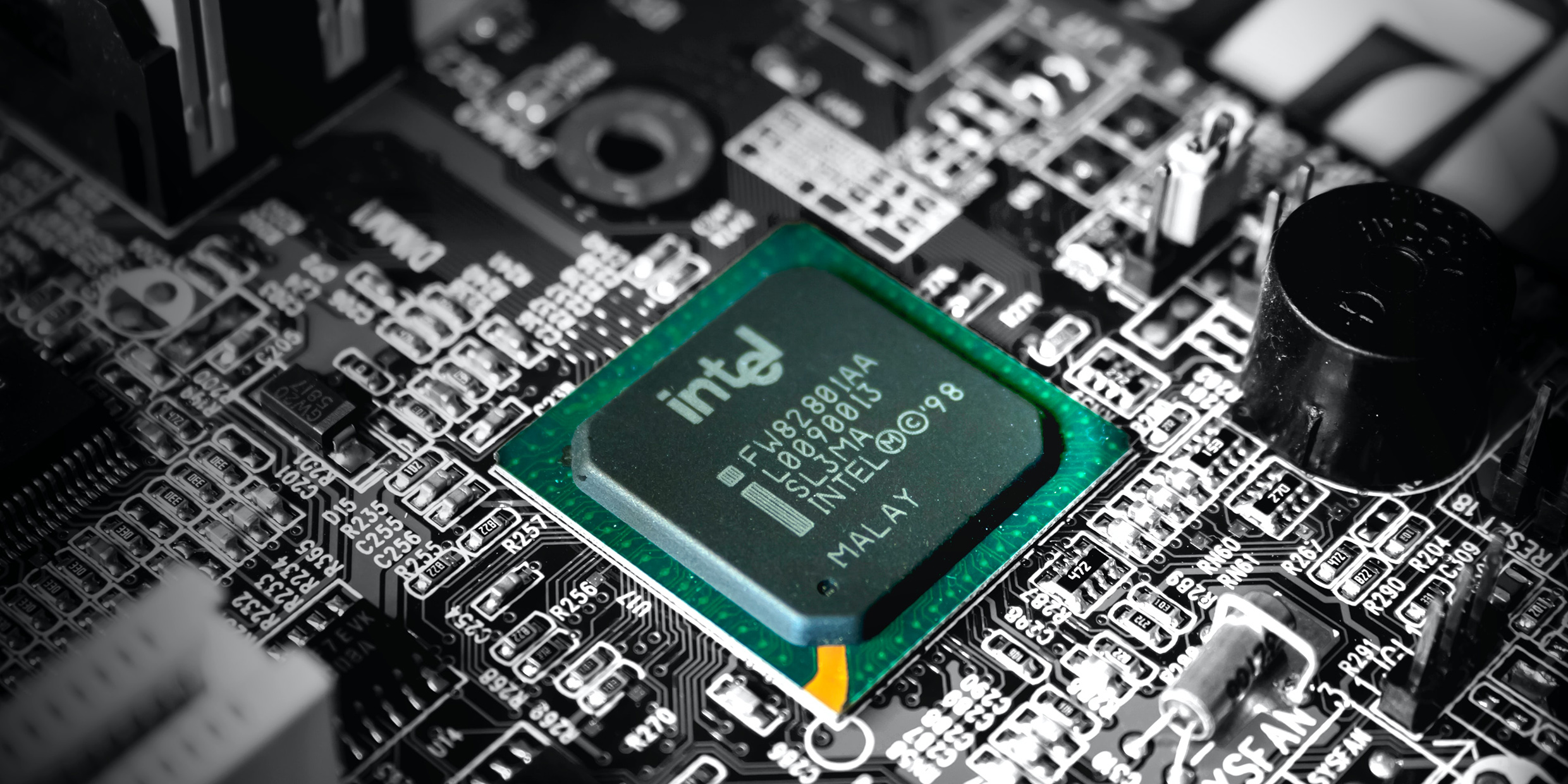

And guess what’s at the top of Chaisson’s curve? Not the human brain, but the Pentium chip, with an energy concentration rate of 10 billion ergs per second per gram. According to Chaisson, we are conceding to computers our place as the most complex things in the universe.

Acclaimed inventor and high-tech entrepreneur Ray Kurzweil sees a direction to history in the ever-increasing speed and volume of information processing. His graph of the processing power of insects, mice, humans, and computers is another exponentially rising curve — with computers at the top.

Another assault on our sense of cosmic primacy.

Twelve years ago, Kurzweil caused a stir with his book The Age of Intelligent Machines, in which he made startling predictions about future developments in information technology. For example, he predicted that a machine would soon outperform a chess grand master. His prediction came true in 1997 when IBM’s chess-playing computer Big Blue trounced grand master Gary Kasparov.

Kurzweil’s most recent book, The Age of Spiritual Machines, makes even more provocative predictions. By 2019, he says, a $1,000 computer will match the processing power of the human brain. Computers will be largely invisible and embedded everywhere — in walls, desks, clothing, jewelry, and household appliances — allowing inanimate objects to respond to our every whim.

By 2029, most of our communication will be with machines, says Kurzweil. People will have relationships with electronic personalities, and use them as companions, teachers, caretakers, and lovers. Virtual sex will be better than the real thing. Machines will claim to be conscious and many of us will believe them.

By 2050, $1,000 worth of computer will equal the processing power of all the human brains on Earth.

Meanwhile, bioengineering will proceed apace. Aging will be slowed or eliminated. Most diseases will be preventable or curable. Electronic implants will supplement the functions of the human nervous system and reverse the effects of organic deterioration. Microscopic robots will produce food in sufficient quantity to feed the world.

By the end of the century there will no longer be a clear distinction between humans and machines.

What are we to make of these predictions of the imminent demise of everything we deem human?

A few folks, such as Kurzweil, embrace the post-human future with enthusiasm. They look back upon the long sweep of cosmic evolution and recognize that humans are a momentary efflorescence, destined to be supplanted by new forms of complexity as surely as people took precedence over insects and mice.

In Kurzweil’s view, the future will be characterized by “greater complexity, greater elegance, greater knowledge, greater intelligence, greater beauty, greater creativity, greater love.” His optimism is similar to that of the Jesuit mystic Teilhard de Chardin, who saw the fulfillment of creation at the end of time, rather than at the beginning.

The majority of people, however, are distressed and frightened by the prospect of a post-human future. The late great chemist Erwin Chargaff and entrepreneur Bill Joy, co-founder of Sun Microsystems, have gone so far as to call for constraints on certain kinds of technological innovation as the only way of preserving our essential humanity.

Many people take refuge from fears about the future in religious fundamentalism, New Age mysticism, anti-technological Luddism, or hippie back-to-nature minimalism.

Kurzweil’s predictions might be wrong, but one thing is certain: The curve of history, as plotted by Chaisson or Kurzweil, will continue to rise at an ever-increasing rate. By the end of this century, humans will possess powers for self-transformation unlike anything even these futurists dream.

We must ask ourselves before it’s too late: What is a human self? What, if anything, is the essential difference between an organism and a machine? Are constraints on human curiosity desirable or possible? Is the human species as we know it today the final destiny of cosmic evolution?

If philosophy departments in our universities want a useful mission, they should introduce young people to the growing technological potential for planetary and self-transformation, and prepare them to make the collective political decisions that will ensure that whatever the future brings, it will indeed be characterized by greater knowledge, intelligence, beauty, creativity, and love.