Originally published 24 May 1993

American high-energy particle physicists want $10 billion of the taxpayer’s money to build the Superconducting Supercollider, a colossal particle-accelerating machine in a 50-mile-long tunnel under the Texas prairie.

Europeans physicists are asking for money too. They want to build a Large Hadron Collider at CERN near Geneva. The price tag is cheaper than for the more ambitious American machine, but still pricey.

The so-called Holy Grail of both machines is the Higgs boson, a massive particle named for the British physicist who proposed its existence as a way of giving a kind of completion to the current theory of particles. The Higgs is supposedly the ultimate particle, the source of mass of all other particles, and the key to uniting the forces of nature. Nobel-prizewinning physicist Leon Lederman has called it “the God particle.” Steven Weinberg’s book on the quest for the Higgs is called Dreams of a Final Theory.

Britain’s minister for science, William Waldegrave, recently issued a challenge at the annual conference of the Institute of Physics at Brighton, England: Can physicists explain — on a single sheet of paper — what the Higgs boson is, and why it is important to find it? If so, said Waldegrave, he would help them get the money. If not, the public has a right to ask “Why?”

He offered a bottle of vintage champagne for the best response.

Not one to pass up a free bottle of champagne, I offer the following, in verse:

Democritus imagined

a world composed of atoms

bumping in the void

(we are abuzz with them,

he thought). Leucippus

and Lucretius gave assent.

And so it went till Thomson,

Rutherford, and others

discovered nature's trinity---

electrons, protons, neutrons.

How simple! These three

were enough to explain

all that exists. But wait.

As physicists banged

these particles about, others

proliferated like bubbles

in champagne---pions,

muons, neutrinos, quarks,

and so on---a froth of troubles

for searchers of simplicity.

More! Electrons, for example,

interact, repelling. How?

By exchanging photons, Richard

Feynman said. Quarks, too,

get sticky by passing gluons

back and forth (a subtle bit

of Dicky physics, but it worked).

And what of the force called

"weak" between, say, a neutron

and an electron, clearly

not electric. Well, let those

particles too exchange a kind

of anti-glue, called Ws and Zs.

All these---and more---the

physicists found with their

machines (God's plan, it seems,

is not inscrutable to man).

But one, alas! The Higgs,

the heaviest of all, the particle

that passing back and forth

gives all others mass. To make it

will require more energy and purse

than you and I possess.

To make things worse,

no one knows for sure exactly

what the Higgs might be, or if

it exists at all. Lest the physicist's

earnest pleas for funds fall

on unreceptive ears, call

it "the God Particle."

There! Who will deny so grand

a quest: to wrest God's

secret plan from nature's grasp.

Cough up. A billion, please,

or ten. Send those protons

flying on their circumferential

path, to crash, to splatter

a shower of Higgses. Ephemeral,

costly, inconsequential,

yet---a flash, a radiance of mind,

the dream of Democritus

confirmed at last. The Final Theory

(for the time being). What? No cash?

Then share, Mr. Minister,

at least, your bottle of champagne,

perhaps in vino to inspire the folks

in Texas and Geneva (and

Russia and Japan) to find

a cheaper way. The search

for the Higgs boson

goes on.

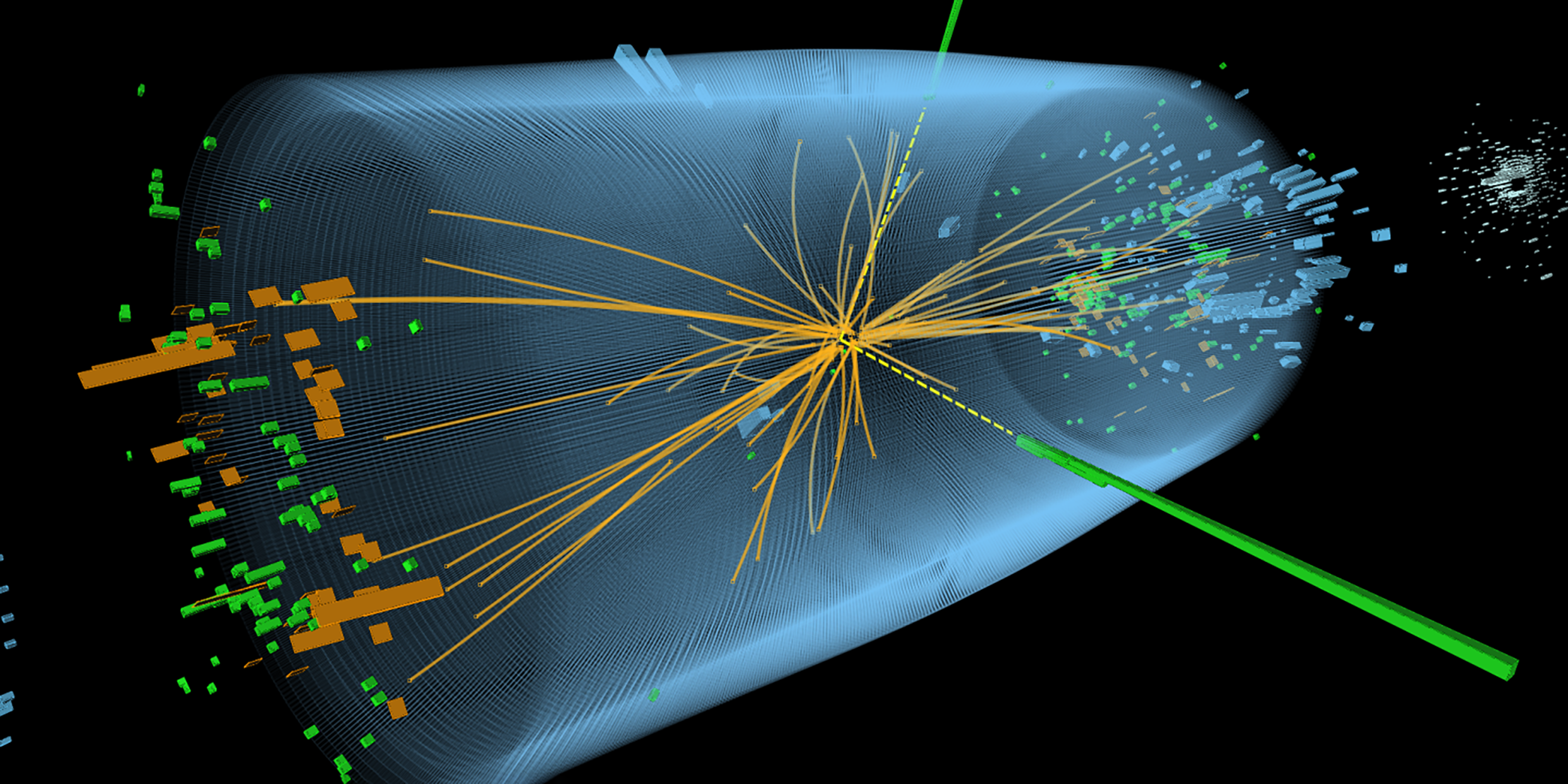

William Waldgreave awarded bottles of champagne for the five best answers to his challenge. The existence of the Higgs boson was confirmed by CERN scientists in 2012, using the Large Hadron Collider, built at a cost of over $4 billion. ‑Ed.