Originally published 4 October 1993

Charles Sims is in town looking for sperm.

Sims is co-founder of California Cryobank Inc., one of the nation’s largest sperm banks. He has his eye on Cambridge for a third office, ideally to be situated between Harvard and MIT. The young men of those universities will be flattered to know that their ivy-twined DNA is so eminently marketable.

If you are in good health, at least 5 feet 9 inches tall, and between the ages of 19 and 34, Dr. Sims may be looking for you. Donors will receive $35 for each accepted specimen up to three times a week. Some time ago, Forbes magazine interviewed a donor to a New York sperm bank who claimed to have made $3,400 a year.

Infertile couples are grateful for the services of commercial sperm banks. Still, there is something profoundly disturbing about treating human genetic material as a commodity. It is not just a vial of milky fluid that the sperm bank buys for $35, but the DNA to make half a human. And $3,400 worth of sperm can create lots of offspring, a circumstance that requires of the donor an astonishing degree of emotional detachment.

Over the ages, empty pockets have prompted many down-and-outers to sell body parts and fluids. Generations of poor women sold their hair to wigmakers. The heroine of O’Henry’s Gift of the Magi sheared her glorious tresses to raise cash for her hubby’s Christmas gift — an unselfish act that never fails to charm sentimental readers.

Blood has also been a ready source of cash.

But sperm? New medical technologies are leading us into an ethical morass, and frozen sperm is just the tip of the iceberg.

At risk is the commercialization of human life.

Most industrial nations prohibit the buying and selling of human organs, but as physicians become ever more adept at transplantation the pressure is on to bend, break, or modify the rules.

The number of people waiting for organ transplants is far greater than the number of organs supplied by voluntary donors. When demand for any commodity greatly exceeds supply, good intentions and thoughtful rules go by the board.

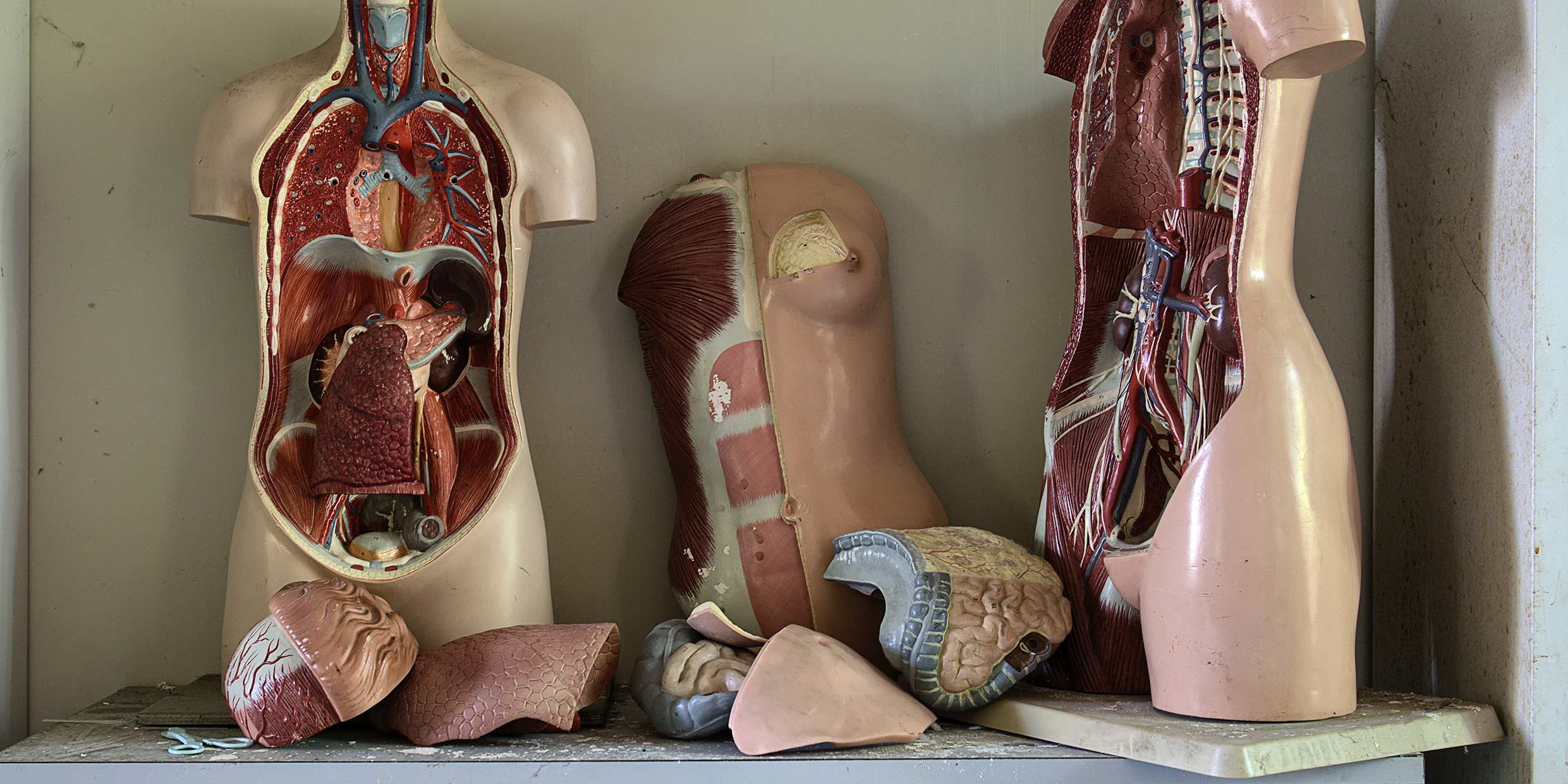

One body can provide a heart, two lungs, two kidneys, a liver, a pancreas, two corneas, two hip joints, a jawbone, six ear bones, limb bones and ribs, bone marrow, and a mess of assorted ligaments, tendons, cartilage, skin, and blood vessels. The market value of the lot is substantial, and even live donors can profit. We require only one kidney; the other might fetch tens of thousands of dollars on an open market. A cornea could command thousands of dollars. A patch of skin is worth hundreds.

A black market in human organs has the potential to turn Third World countries into body-part depots for the wealthy nations.

If laws are changed to allow the regulated buying and selling of organs — as some physicians and potential transplant recipients suggest — enormous pressure will come to bear on the world’s poorest citizens to market their bodies. In the grimmest scenario, death would be a welcome windfall for the family of the deceased.

If the supply of organs continues to depend only upon the altruism of voluntary donors, thousands of people will die who might otherwise be saved by a timely transplant.

If regulated commerce in organs is made legal, then the last vestiges of sacredness will be removed from the human frame. The entire body will be as casually marketed as hair, blood, and sperm.

The Renaissance poet John Donne said of himself: “I am a little world made cunningly of elements, and an angel-like spright.” He knew there was more to the body’s ensemble than organs and fluids. One need not believe in disembodied souls to accept that we are more than the sum of our parts. If we aspire to the angelic, we should resist the temptation to treat our bodies as so much marketable meat.

On the other hand, who among us would not be grateful for the chance to buy a heart or kidney if it would save our own life, or the life of someone we love? Who would not welcome the opportunity to buy a cornea if it would restore our sight? How many thousands of childless couples are made happy by $150 vials of frozen sperm?

In Donne’s time, the “little world” of the body was thought to mirror the larger world of the cosmos. From the element of fire, humans received their sight; from water, taste; from earth, touch; from air, the senses of hearing and smell. Each organ of the body had a celestial correspondence in sun, moon and planets. The human frame was connected by a web of correspondences to everything that exists, imbuing it with a sacredness, wholeness and uniqueness that ennobles life.

This medieval wisdom should not be lost as we grapple with the moral dilemmas posed by the new reproductive and transplant technologies.