Originally published 13 January 1997

The Enlightenment has been taking its knocks lately.

New Age and academic critics of science assure us that the Enlightenment has run its course, that the 18th century’s supreme confidence in the rational powers of the human mind was mere hubris. We are entering a post-Enlightenment age, they say, when science will be demoted to drudge stepsister of technology.

In place of science will come knowledge that is subjective, not objective, qualitative, not quantitative, available to everyone, not just to a scientific elite, faith-based and non-empirical. In this new order, the primacy of science will give way to a multiplicity of ego-centered knowledge systems, all of which will be considered equally authoritative.

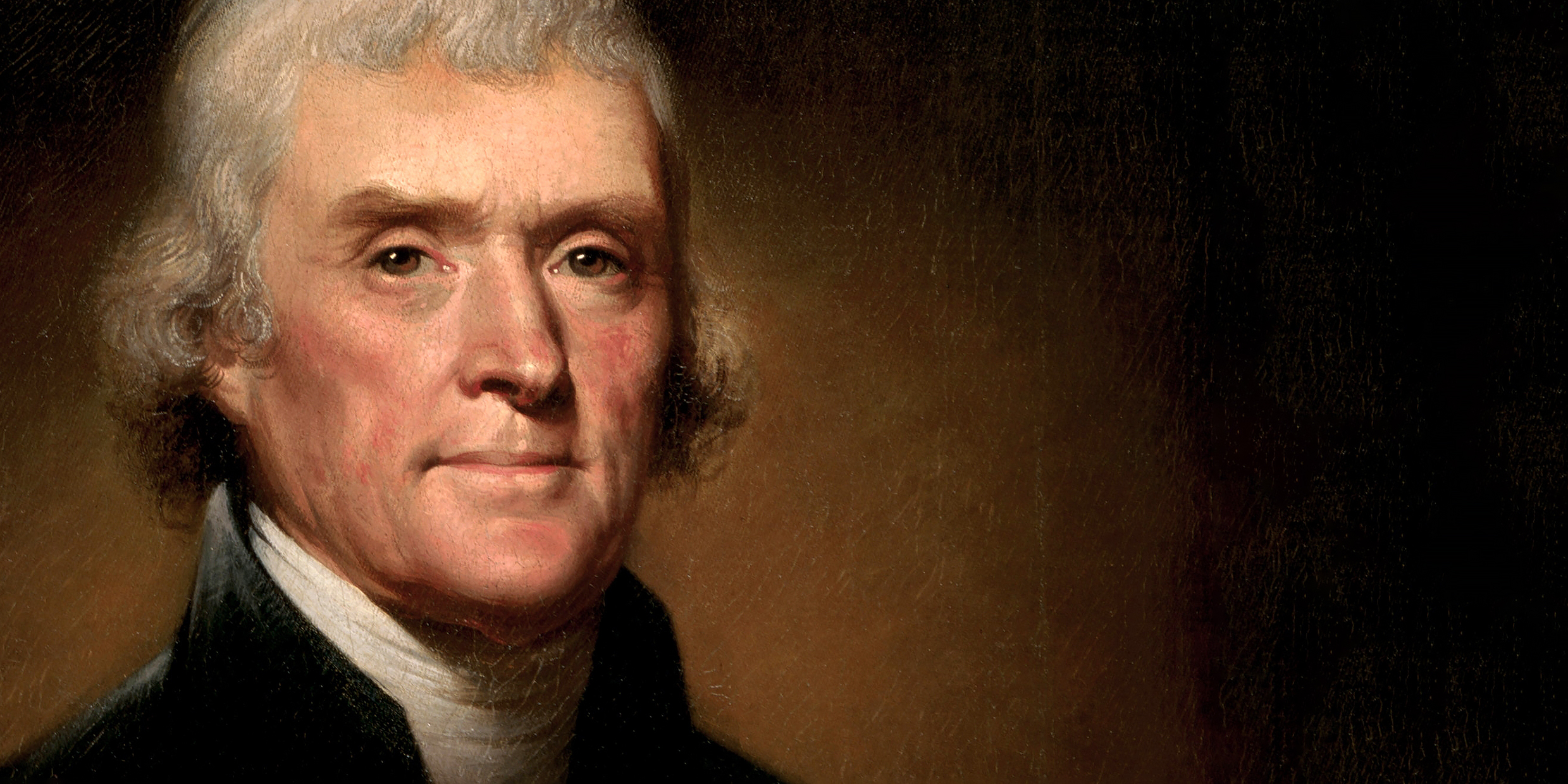

Thomas Jefferson must be turning in his grave.

Jefferson was the embodiment of the Enlightenment, and architect of the American experiment in Enlightenment democracy. In place of the autocracies and theocracies of Europe, he imagined a nation founded upon self-evident truths of reason, among which stand the natural equality of all men and the derivation of the powers of governments from the consent of the governed.

Jefferson was not a perfect man, and his notion of natural equality did not extend to his own Black slaves, but by and large the nation has been well served by his visionary confidence in the ameliorating power of reason.

He envisioned a vast empire of equals, extending from coast to coast, governed by consensus, ennobled and enriched by the bounty of the land.

To further this end, Jefferson conceived and caused to be executed a bold journey of discovery across the terra incognita of the American West, from the Mississippi to the Pacific. He chose his personal secretary Meriwether Lewis as leader of the expedition; Lewis chose William Clark to share the command.

Every American schoolchild learns about the Lewis and Clark expedition. Few learn how profoundly the expedition was grounded in the ideals of Enlightenment science.

The journey up the Missouri River and down the Columbia River was no mere exercise in imperialist land-grabbing. A quest for empire, yes, but Jefferson also wished to add to the store of human knowledge. Objective, quantitative scientific knowledge, he believed, was the driving engine of the public weal.

It was therefore essential that the captain of the expedition be a skilled naturalist. Lewis’ scientific education began at Jefferson’s dinner table, where he took his meals with the president and his quests. Conversation was as likely as not to turn on natural history, astronomy, geography, mineralogy, natural philosophy (which we now call physics), and the habits and languages of the native North Americans.

Lewis was a quick learner. He had the run of Jefferson’s remarkable library and collection of maps. Jefferson himself was as broadly knowledgeable a teacher as might be found in America.

Once Lewis accepted his commission to lead the expedition, there followed a period of intensive scientific training, including the use of the sextant, chronometer, telescope, and other instruments. He was taught by experts how to collect and preserve specimens of plants and animals he would encounter along the way.

In Philadelphia, Lewis gathered a traveling library, which included such works as Barton’s Elements of Botany, Kirwan’s Elements of Mineralogy, and The Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris. He went into the wilderness better equipped for scientific discovery than any explorer before him.

As Lewis’ biographer Stephen Ambrose writes: “There was no hint of encouraging exploration for its own sake or merely to satisfy curiosity about what was out there. This was a true Enlightenment venture.”

And what a grand adventure it was, full of hardship, heroics, misadventure, mischief, triumph, and tragedy. It encapsulated all of the defining characteristics of American civilization, good and bad. And behind it all, at every moment and in every place, stood the spirit of Jefferson.

American science and American democracy stemmed from the same root: a confidence in the goodness and rightness of nature, and in the power of the human mind to rightly order the affairs of men. For Jefferson, the Divine Will was not evidenced in kings and prelates, but in the natural order, to be made evident by patient observation and experiment. His greatest experiment was the Nation, prosperous, free and indivisible, stretching from sea to shining sea.

As Meriwether Lewis entered into his journal each day’s observations of birds, plants, native languages, and geography hitherto unknown to science, he knew he was part of that experiment, accumulating what Jefferson called “useful knowledge” — useful to the building of a civil and democratic society.

And now we are told that the Enlightenment experiment is coming to an end. If so, we can only wait and see whether whatever replaces it will contribute more to the nation’s life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness than did the guiding principles of Thomas Jefferson and Meriwether Lewis.