Originally published 1 August 1988

Next month [Sep. 1988] the planet Mars will be closer to Earth than at any time since 1971. For telescopic observers in mid-northern latitudes, the viewing will be best since 1955. Professional and amateur astronomers will be closely examining our neighboring planet for dust storms and changes in cloud cover and polar ice. A knowledge of Martian wind and weather will be important for the future exploration of that planet.

It now seems likely that humans will visit Mars early in the next century. I would not be surprised if there were permanent colonies on Mars before the middle of the 21st century. But armchair travelers need not wait. NASA has produced excellent maps and atlases of Mars from data supplied by the Mariner and Viking spacecrafts. With the help of the maps it is fun to take imaginary journeys on the surface of the red planet.

Let’s begin an expedition of discovery from a base in the Chryse Planitia (the Plains of Gold), a dusty, rock-strewn basin just north of the Martian equator, near the spot where Viking 1 touched down in 1976 in its search for life. The derelict spacecraft is still there, the silent victim of many dust storms, but otherwise not much worse for wear. It is preserved by our 21st century colonists as a historical monument of early Martian exploration.

From the plains of Chryse our caravan of nuclear-powered vehicles follows a dry watercourse up to the lava highlands of the Lunae Planum (Plateau of the Moon). One of the surprises of early Martian exploration was the discovery of many of these eroded “riverbeds” on the surface of Mars. The channels are evidence of great floods in the planet’s past, possibly caused by the rapid release of subsurface water at a time when the atmosphere was denser and the temperature higher than now. Today, most of the planet’s water is frozen in the ground as permafrost. Mined and melted, these frozen reservoirs supply adequate water for colonists.

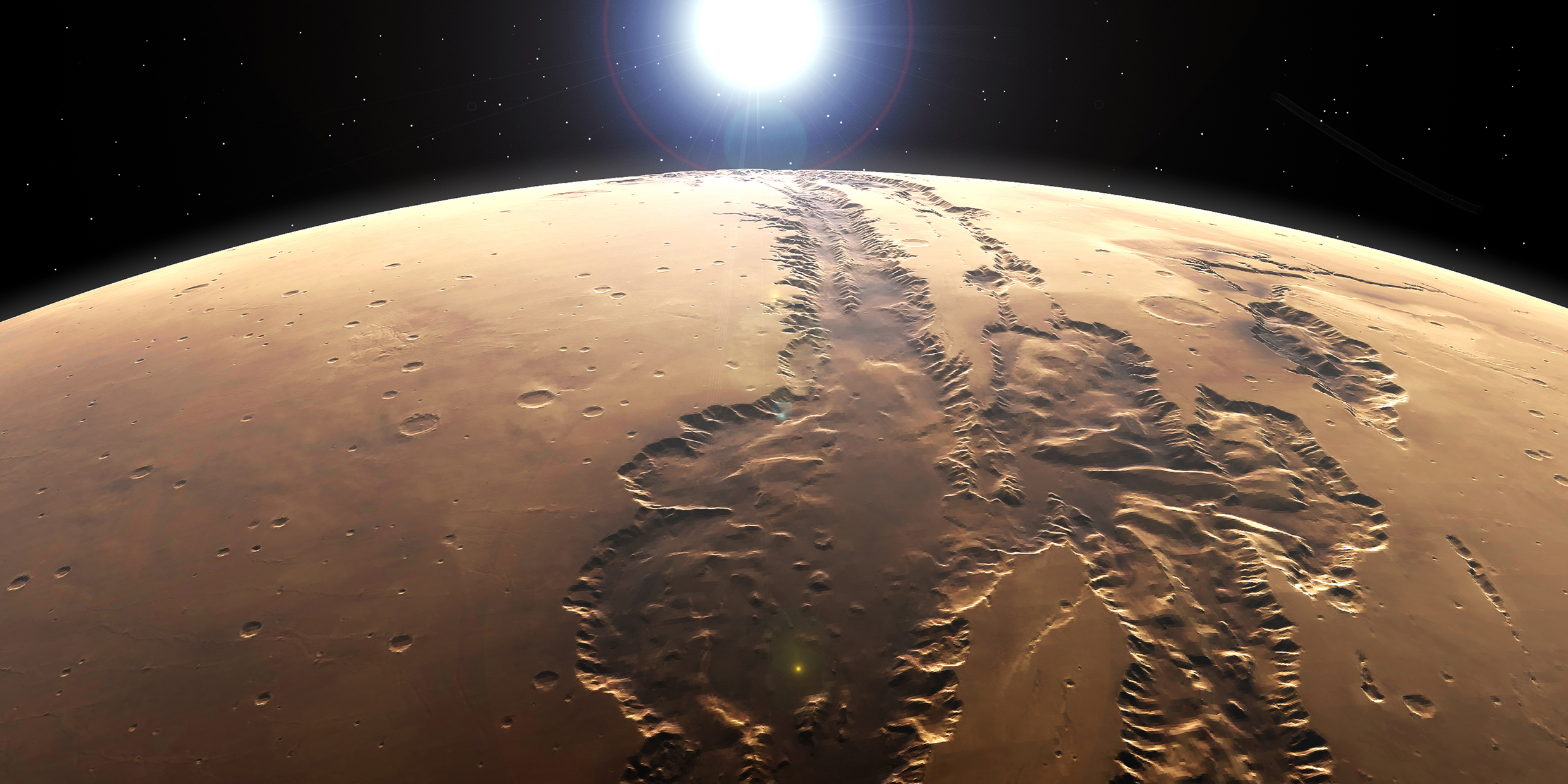

A monstrous chasm

At the head of the Lunae Planum, a thousand miles from home base, our expedition crosses the Martian equator and arrives at the rim of a vast east-west system of canyons called Valles Marineris, named for the spacecraft that first photographed these features. The Grand Canyon of Arizona is a mere scratch compared to the gaping chasm that lies before us. If on Earth, the Valles Marineris would reach from New York to San Francisco. In places the floor of the canyon lies four miles below the rim. This colossal gash in the planet’s crust was apparently caused by a stretching and breaking of the crust, rather than by erosion.

A Martian sunrise viewed from the rim of the Valles Marineris is particularly beautiful. Just before the sun appears on the distant horizon, the sky in the east glows an eerie blue-green. As the sun rises, morning frosts and haze dissipate from the walls and floor of the canyon. The sun appears a third smaller and less than half as bright as from Earth. As the day progresses, the color of the sky ranges through subtle shades of pink and yellow, depending upon the angle of the sun and the quantity of dust particles suspended in the atmosphere.

Here, near the equator of Mars, the outside temperature is actually quite comfortable early on a summer afternoon, although at night it plunges a couple of hundred degrees Fahrenheit below freezing. The nocturnal cold is relatively easy to deal with. More difficult problems for our explorers are the sparse oxygen content of the atmosphere, the absence of liquid water, and ultraviolet radiation from the sun. Another problem encountered by our expedition are dust storms that occasionally impede our progress. These are most common in the southern hemisphere of the planet, but occasionally a storm develops sufficient energy to engulf the entire planet with sky-obscuring, wind-driven dust.

Our caravan moves westward along the rim of Valles Marineris. At the head of the canyon we skirt a region of fractured, chaotic terrain known as Noctis Labyrinthus (The Labyrinth of Night). Here the crust of the planet has been broken into irregular blocks separated by huge canyons by a force pushing up from below. And on the far horizon appears another evidence of intense geologic activity — the Tharsis Montes, three spectacular volcanic peaks rising starkly from the surface of the high plateau.

Olympus Mons

But we do not tarry. The terminus of our journey lies another thousand miles away across difficult volcanic landscape. We notice it first as a patch of white cloud hanging on the horizon. Nothing we have seen on Earth prepares us for what we find beneath that cloud — a mountain of staggering proportions, an almost perfect volcanic cone, 300 miles wide at the base and rising from the plain to a height more than twice that of Everest. It is Olympus Mons, the largest known mountain in the solar system.

The Brobdingnagian scale of the canyons and peaks of Mars (on a planet half the size of Earth) is partial compensation to our explorers for an otherwise bleak and dusty landscape. Surely, however, the greatest attraction for the colonizers of Mars is the challenge of being first in the the great outward movement of the human species from their home planet.