Originally published 8 July 2003

All human knowing is metaphorical.

As we explore the world, we explain the unfamiliar in terms of the familiar. For example, we variously speak of protons and electrons as particles (“tiny billiard balls”), or as waves (“like water lapping a shore”).

As the unfamiliar becomes familiar, it also can serve as metaphor. The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle of physics, which addresses events on the subatomic scale, for example, is sometimes evoked by literary writers to illustrate how the act of observing changes the thing observed, even on a human-sized scale.

We are most familiar with the human self, so it is natural that we use the metaphor of self to explain the world. Our ancestors imagined that every mountain, brook, and tree had a humanlike spirit. Their gods, too, invariably had human features.

Problems arise when we confuse metaphor with reality. Physicists of the early 20th century found themselves in a dither when neither particle nor wave served adequately to describe subatomic particles. And the metaphor of gods who are like ourselves has caused no end of religious strife.

None of this, of course, is any great revelation, but I’ve been thinking about it during the blitz of media attention to the SARS virus.

A virus resists categorization as alive or dead, the two mutually exclusive categories we use to describe the world. Viruses share certain characteristics with living things; they are made of the same chemical stuff and use similar genetic machinery to reproduce. But viruses are unable to reproduce on their own; for this they must hijack the chemical apparatus of creatures that are more unambiguously alive, ourselves, for instance.

So a virus is not quite alive but also not quite dead. It is rather like saying that electrons behave sometimes like particles and sometimes like waves.

The muddle of metaphor goes further. We tend to think of viruses as living, and to be alive means to be more or less like ourselves. So there is an inclination to endow the SARS virus, say, with moral purpose — a malicious beast intent on doing humans harm, like a wolf or rattlesnake writ small.

Small, yes, many times smaller than a bacterium; 10,000 SARS viruses could line up across the head of a pin. But a virus has almost nothing in common with life on the human scale, and metaphors like “malicious” or “beast” are misplaced.

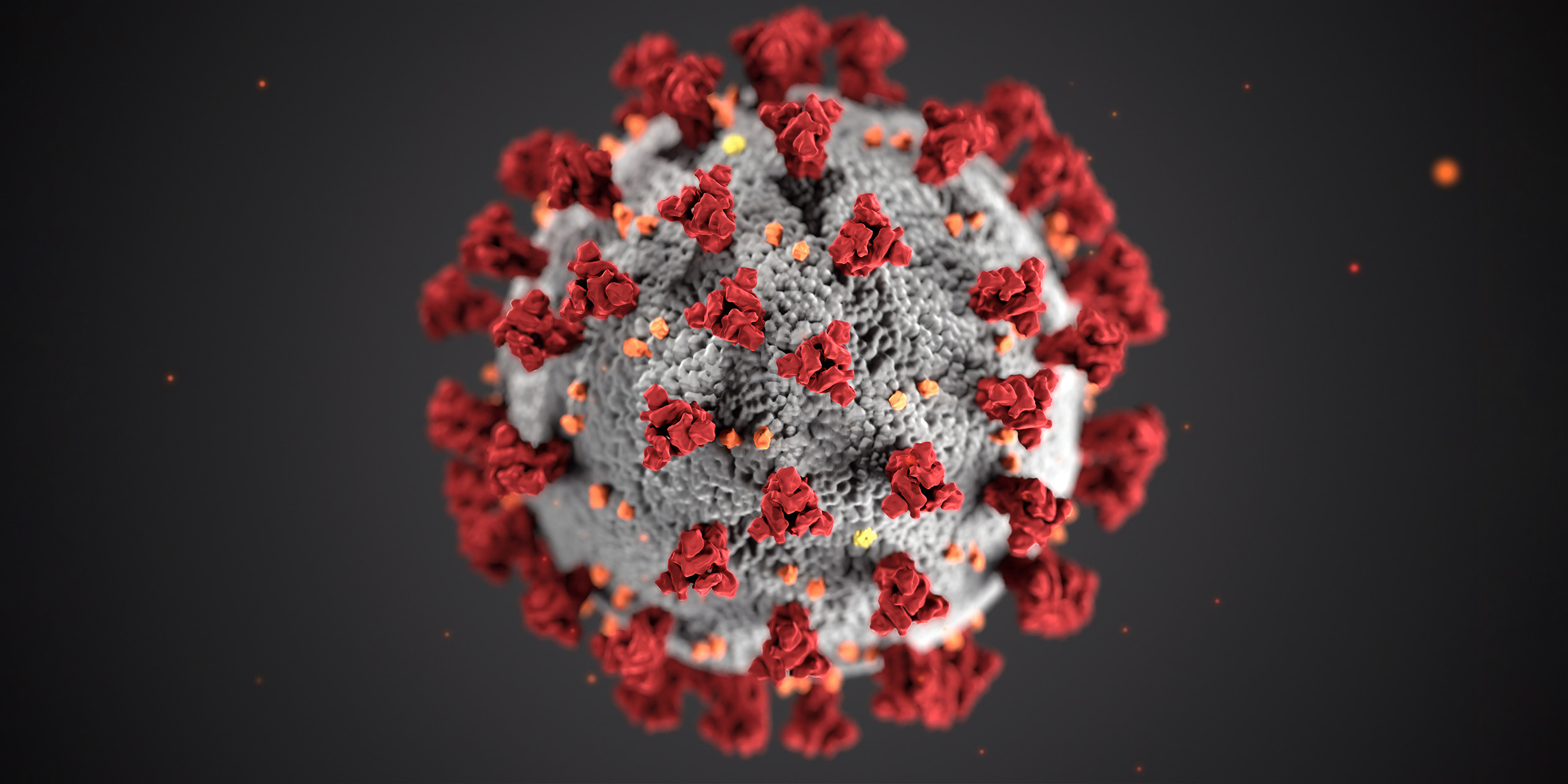

The SARS virus is nothing more than a snippet of genetic material — RNA — in a protein wrap. If you could see it, it would be a pretty little thing — a spherical jewel box studded with spikes. Inside the box, a coil of RNA about 100-thousandth as long as the human genome.

The “prettiness” of a virus derives from the fewness of its genes. It has only enough genetic information to make a handful of proteins, so to build a shell for its RNA it must use the same few proteins over and over, like the repetitive pattern of patches on a soccer ball or the polygonal plates of a geodesic dome.

But to speak of a virus as “pretty” is to impose another human metaphor. Pretty is irrelevant. Purpose is irrelevant. Mischief is irrelevant. Every metaphor we can marshal is inadequate.

A virus is…well, a virus is life reduced to its bare essence, and then a little beyond. Unable to live on its own, a virus must parasitize another organism. The SARS virus probably infected a yet-unidentified mammal, bird, or reptile before it evolved the ability to co-opt human cells.

And there, inside our bodies, it goes happily about the business of making more of itself, at our expense.

Just listen to those metaphors. “Happy.” “Business.” “Self.” “Expense.”

Human metaphors do not take us far in understanding viruses. But viruses help us understand ourselves. It can be as useful to think of a human as a virus writ large as to think of a virus as a human writ small. It focuses our attention on the fact that our bodies — including our brains — evolved as colonies of genes driven by an ineluctable biochemical force to make copies of themselves.