Originally published 5 September 1983

Life is almost as ancient as the earth itself. Precisely how, when and where life made its debut on planet Earth may never be known. But most contemporary scientists agree that the first living cells arose from spontaneous arrangements of non-living matter.

Even the simplest living thing — a bacterium, for example — seems marvelously advanced over the most complex non-living structures. If ever there was a “missing link,” it is the giant step between the shelf of dead chemicals and the living organism. That the animate should arise from the inanimate must always seem a bit of a miracle.

Why did the miracle happen only once, three-and-a-half billion years ago, and not again since? In Darwin’s day it was protested that if life came from non-life at some time in the past, then we should see the same thing happening today. New creatures should spring from every fetid pool. Every rain barrel should clamor with exotic organisms. And, of course, such things do not happen. In our experience, life — always, invariably, reliably — comes only from life.

Darwin had a wise reply: If a simple form of life appeared spontaneously today, it would immediately be devoured or absorbed by living creatures. In our present environment, life is pervasive and voracious. A fresh starter wouldn’t have a chance.

What is required for the spontaneous genesis of life, said Darwin, is a “warm little pond,” rich with the right chemicals and free of living predators. Darwin’s “warm little pond” was the planet Earth about three-and-a-half billion years ago.

More precisely, the “warm little pond” was Earth’s thin skin of water and air. Without that gossamer film of fluids the Earth would be as lifeless as the Moon.

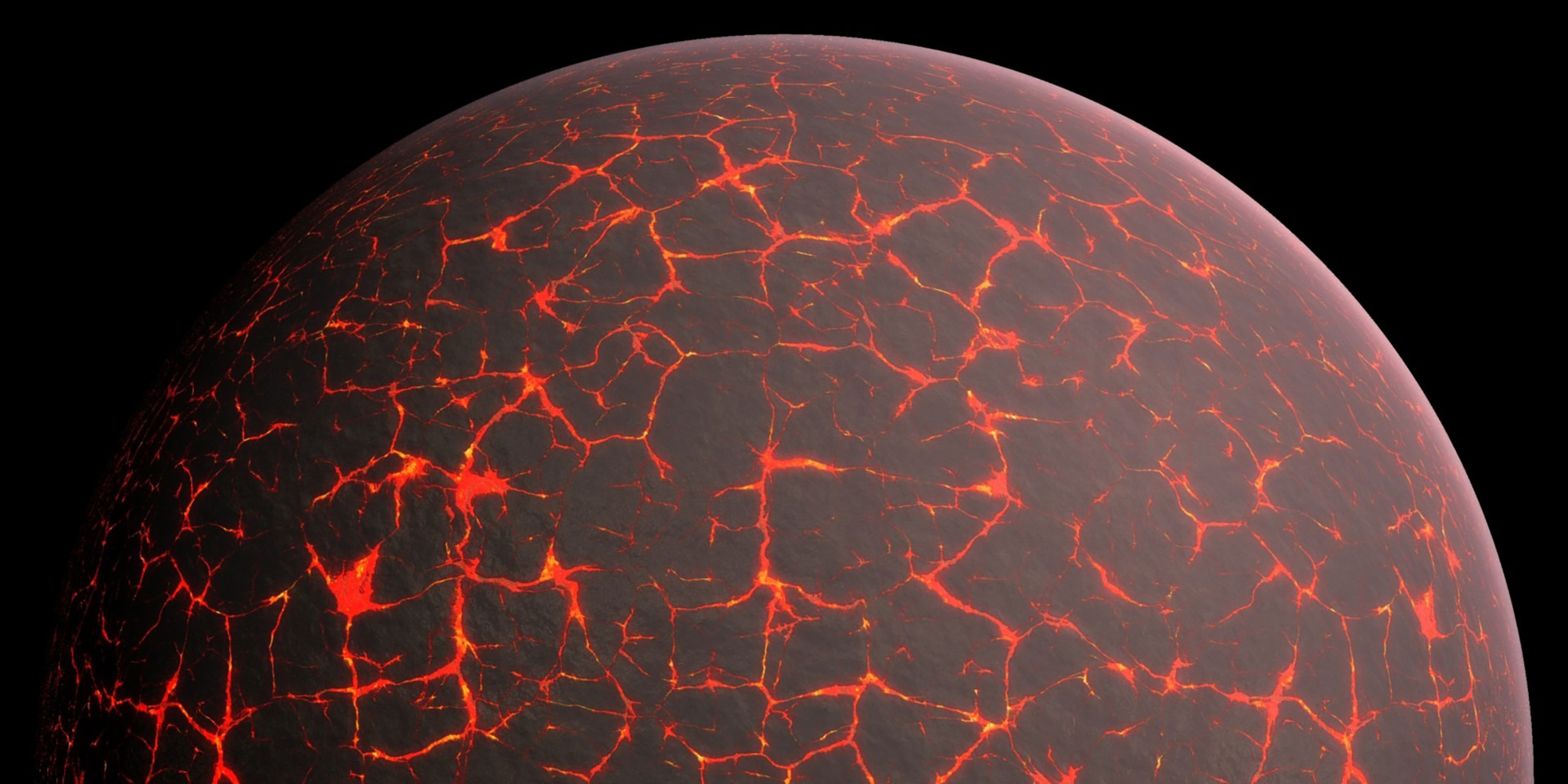

The molten Earth

The Earth would be as barren as the Moon except for one extraordinary event: Early in its history, the planet melted.

The Earth was warm at its formation. The squeeze of gravity, radioactivity, and the bombardment of asteroids heated it further. A good part of the Earth’s bulk is iron, and of the major materials that make up the Earth, iron is the heaviest and has the lowest melting point. When the temperature of the warming Earth reached the melting point of iron, the iron liquefied and fell toward the center, displacing lighter rocky materials. This “big burp,” this huge turnover of the Earth’s substance may have been the most momentous event in the planet’s history. The falling iron, like a pile driver, released energy in the form of still more heat. The planet melted. Perhaps it melted completely. Perhaps it became a big red liquid bubble of molten metal and rock.

When the planet melted, the water and gases that were trapped in the body of the planet escaped to the surface. They bubbled from the surface of the molten Earth even as they do today from volcanoes, geysers and hot springs. The water, of course, was in the form of steam. The surface of the planet was still too hot for water to exist as a liquid.

The surface of the young planet may have looked like the churning fire-pit of Hawaii’s Kilauea volcano, covered with broad lava lakes that crust over and quickly melt again. Eventually, as the planet cooled, a permanent crust began to accumulate like a scab on a raw wound. Even as the crust formed, it was bombarded by meteorites, chunks of rock and iron left over from the formation of the Solar System. For millions of years there was a rain of stone from the sky, pummeling the surface of the young planet. More water and gases may have arrived with the meteorites to become part of the accumulating atmosphere.

Perpetual rain

As the Earth cooled, water vapor in the atmosphere began to condense into droplets and fall as rain. At first, when the rain fell onto the hot crust it boiled off as steam, like drops of water flung onto a hot griddle. The steam rose into the atmosphere, condensed, and fell again. It rained everywhere on the hot cloud-darkened planet. For thousands of millions of years there was not a sunny day, not one starry night. Lightning crackled continuously. Eventually the surface cooled to the point where where could remain liquid. It sizzled and steamed on the flanks of volcanoes. It cascaded into the lowland basins and the bowls of impact craters. At last the skies began to clear and the sun glistened on a sparkling sea. The Earth had acquired an ocean.

When the skies cleared, when the volcanoes quieted and the cosmic bombardment slackened, the Earth was encased in a film of air and water. It was still a bleak and barren place, still warm from its birth and bathed in radiation from the sun. But as violence from above and below subsided, it was undeniably home.

And so was Darwin’s “warm little pond” prepared for the coming of life.

Life from afar

Some scientists have suggested that life arrived on Earth from elsewhere, fully formed. It might have arrived by accident, they claim, as a passenger on a meteorite or comet. Or the Earth might have been “seeded” by an extraterrestrial civilization.

But it hardly seems necessary to invoke an outside origin for life. All the elements required for life were available in the early oceans and atmosphere. There was plenty of energy available to transform the chemicals of life into living organisms. The pond was stocked with the right ingredients. The pond was warm. Earth was poised for the miracle of life.

Perhaps no one has experienced more profoundly the special character of the Earth as a suitable environment for life than the few creature who have left its surface. The astronauts who went to the moon took a bit of the “warm little pond” with them, backpacks full of the fluids and gases which are the medium of life on Earth. Standing on the cold, dry, airless lunar plains they looked out into the black void of space and saw the planet Earth hanging from the sun by a slender gravitational thread, glistening in its delicate sheath of sea and cloud.