Originally published 21 December 1992

Every year about this time I am asked by friends and colleagues to recommend good science books for kids, to fill the remaining hollows in Santa’s pack.

There are lots of terrific science books out there, and a good place to find them is the children’s book section of the Museum of Science shop. But my advice to parents is: Don’t be overly worried about providing science books for your kids. Expose them to good children’s literature and the science will take care of itself.

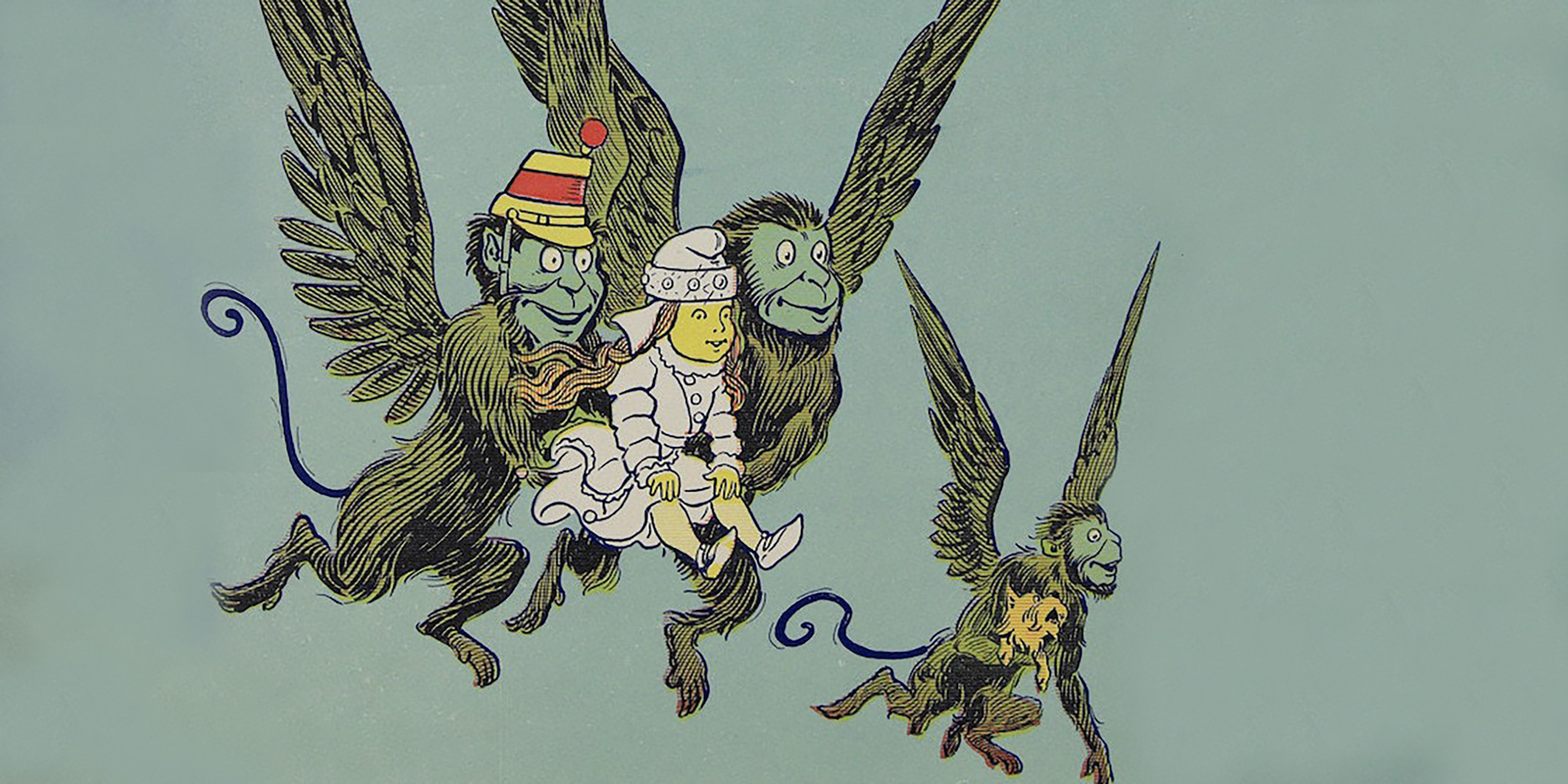

Over the years I have often made reference to children’s books in this column, including the nonsense books of Dr. Seuss, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-glass, Frank Baum’s Wizard of Oz, Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, and Felix Salten’s Bambi.

All of these in essays about science.

What’s the connection?

Children’s books capture the curious, willing-to-be-surprised, “let’s pretend” quality of good science. Children’s books are full of the playfulness that is part of all first-rate science. And, like science, children’s books insist upon the reality of the unseen.

Science books for children are packed full of interesting information. What most of these books do not convey is the story of how the information was obtained, why we understand it to be true, and how it might embellish the landscape of the mind. For many children — and adults too — science is information, a mass of facts. But facts are not science any more than a table is carpentry.

Science is an attitude toward the world — curious, skeptical, undogmatic, and sensitive to beauty and mystery. The best science books for children are the ones which convey these attitudes. They are not necessarily the books labeled “science.”

From a “science” book we might learn that a flying bat might snap up 15 insects per minute, or that the frequency of its squeal can range as high as 50,000 cycles per second. Useful information, yes.

But consider the information in this poem from Randall Jarrell’s The Bat-Poet:

A bat is born Naked and blind and pale. His mother makes a pocket of her tail And catches him. He clings to her long fur By his thumbs and toes and teeth. And then the mother dances through the night Doubling and looping, soaring, somersaulting--- Her baby hangs on underneath.

Oh what wondrous information! Even the rhythm of the poem (“naked and blind and pale”; “thumbs and toes and teeth”) mimics the flight of mother and child, doubling and looping in the night.

More:

The mother eats the moths and gnats she catches In full flight; in full flight The mother drinks the water of the pond She skims across. Her baby hangs on tight.

That wonderful line — “In full flight; in full flight” — conveys the single most important fact about bats: their extraordinary aviator skills. Jarrell’s repeated phrase conveys useful facts about chiropteran dining; it also lets the child feel in her bones what it is to be a bat.

In Jarrell’s book, the Bat-Poet recites his poem about bats to a chipmunk. Afterwards, he asks, “Did you like the poem?”

The chipmunk replies, “Oh, of course. Except I forgot it was a poem. I just kept thinking how queer it must be to be a bat.”

The Bat-Poet says, “No, it’s not queer. It’s wonderful.”

That’s what good children’s literature does — makes us feel the queerness and wonderfulness of nature. It’s the best possible introduction to science.

Albert Einstein wrote: “When I examine myself and my methods of thought, I come to the conclusion that the gift of fantasy has meant more to me than any talent for abstract, positive thinking.” The best time — perhaps the only time — to acquire the gift of fantasy is childhood. We live in an age of information. Too much information can swamp the boat of wonder, especially for a child. What children need is not more information, but fantasy.

Einstein also wrote: “The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of all true art and true science.” At first, this might seem a strange thought. We are frequently asked to believe that science is the antithesis of mystery. Nothing could be further from the truth. Mystery invites the attention of the curious mind. Unless we perceive the world as mysterious, we will never be curious about what makes it tick.

Excerpt from The Bat-Poet by Randall Jarrell reprinted with permission of Macmillan Publishing Company. Copyright © Macmillan Publishing Company 1964.