Originally published 6 February 2001

The mid-19th century was fossil time in science.

Finding fossils was all the rage, by professional scientists and amateur naturalists. Within a few decades, tens of thousands of fossil animals and plants had been named and classified. Some were similar to living organisms. Others were strikingly different.

Of course, fossils had been a source of speculation since antiquity. But the Industrial Revolution and European expansion around the globe opened up rocks for examination as never before — mines, roads, railroads, canals. The rocks were replete with fossils. Thomas Huxley’s biographer, Adrian Desmond, said: “It was the equivalent of finding a new continent of creatures, underground.”

The flood of fossils called for understanding. There was simply no way to wedge this sprawling continent of extinct creatures into the tidy paragraphs of Genesis. Perhaps never before in history had so much intractable knowledge been acquired so quickly.

Then, in 1859, Charles Darwin published his great book and turned the world upside down. The unity of life by common descent over geologic time gave paleontologists the conceptual framework they needed to make sense of the fossils. Suddenly everything fell into place; the scattered jigsaw pieces fit together to make a lovely picture.

Huxley had seen the implications of the fossils. He wrote: “To the very root and foundation of his nature, man is one with the rest of the organic world.”

Something similar is happening today, another flood of biological data, another hidden continent revealed, this time not in the rocks but in the cells of living organisms.

It’s genome time in science.

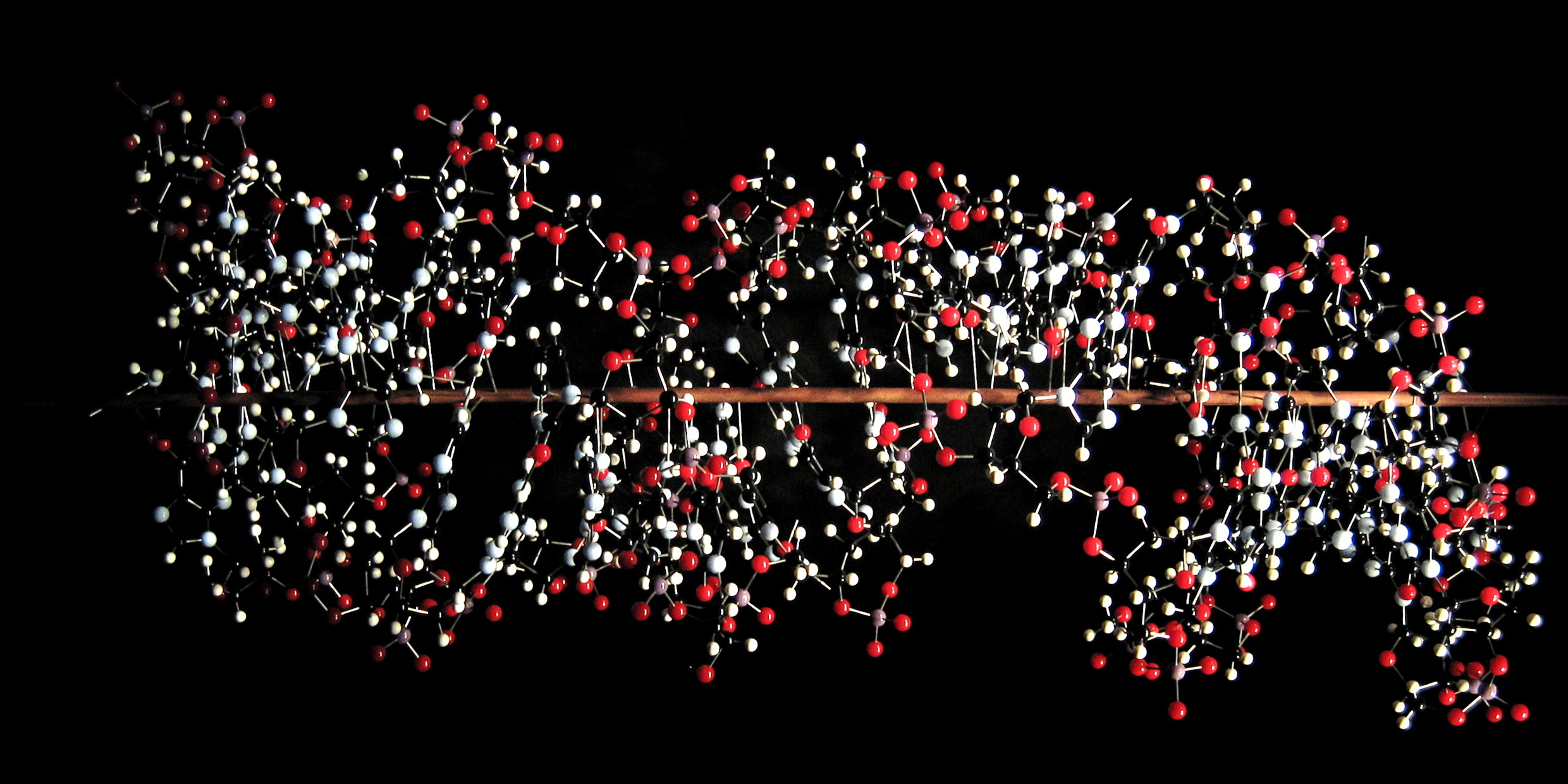

In every cell of every organism are molecules of DNA, chemical spiral staircases in which each tread is one of four pairs of chemical subunits called bases, dubbed A‑T, T‑A, G‑C, and C‑G. The same “four-letter” code is common to every living organism; it is the sequence of the four letters that makes one creature different from another.

Strings of base pairs along the DNA are the genes that make the proteins that make our minds and bodies work. The sum of all the genes is an organism’s genome. The human genome contains several billion base pairs, and something like 100,000 genes coding for 100,000 different kinds of proteins. A fruit fly’s genome is less than a tenth that size. A bacterium’s genome might be only a thousandth as big as a human’s.

A year ago, the genome of only one multi-cell organism, a tiny worm called Caenorhabditis elegans, had been sequenced. Today, we have sequences for the human, the fruit fly, and two plants, including, most recently, rice. Other animals and plants will be sequenced soon. The data bases are overflowing with As, Cs, Gs and Ts.

None of this would have been possible without the cyber equivalent of the Industrial Revolution. Francis Collins, director of the National Human Genome Research Institute, is quoted in the journal Nature: “The stage is set for a full scale exploration of the ways in which this disarmingly simple one-dimensional instruction book is converted into the four dimensions of space and time that characterize living organisms.”

Collins puts his finger on the astonishing significance of the genomic revolution: The way in which the almost infinite complexity of life emerges from a molecular code of mind-boggling simplicity.

It is not enough for the DNA to spin off proteins. It must spin off the right proteins at the right time and in the right place in the life cycle of an organism, and do so reliably throughout the life of the organism. As I sit here typing, all of that wonderful molecular machinery is spinning and weaving in every cell of my body.

Ultimately, the formation of thoughts in my head as I type and the moving of my fingers on the keyboard of my laptop depend upon an unceasing whirlwind of chemical activity that I can’t see or feel, and that until recently we knew nothing about.

And we still don’t know a lot about it. The more we learn about how biological complexity arises from molecular simplicity, the more I get the sense that nature is trying to tell us something we don’t yet know, perhaps something as radically new as Darwin’s glorious vision of the unity of life.

During the coming weeks, months and years, the torrent of genomic information will continue, not just sequences of As, Ts, Gs and Cs, but also an understanding of the proteins they code for and how the proteins work. Ever-more-powerful computers will tease out patterns that elude human recognition, and maybe — just maybe — a new Origin of Species is in the offing.

The genomic revolution has made it more clear than ever that “to the very root and foundation of his nature man is one with the rest of the organic world.” Perhaps we will now learn something surprising about those roots and foundations.