Originally published 27 June 2000

We can’t do without bacteria. Some of them cause mischief but others are essential for our survival.

Without “nitrogen-fixing” bacteria, for example, the whole human enterprise would come to a halt. These bacteria take nitrogen from the air and build molecules that are useful for life, something we can’t do by ourselves.

And that’s just for starters. Bacteria play a hugely important role in maintaining the ecological balance of the planet. Eliminate bacteria and the whole pyramid of life would come crashing down.

But what about viruses? Are viruses necessary for the well-being of the planet, or are they merely troublemakers — nasty little parasites that the world can do without?

What is a virus, after all? A snippet of renegade RNA or DNA in a protein shell. A submicroscopic packet of disruptive strife. Viruses are not quite alive and not quite dead. They lack the genetic information to make their own energy or proteins. They can only reproduce and build their protein shells by hijacking the chemical apparatus of an invaded cell.

And what they leave behind is a mess. Their name comes from the Latin for “poison.” Just look at the devastation wreaked by the current AIDS epidemic in Africa. Or the 1918 influenza pandemic that claimed 20 to 40 million lives worldwide. Both caused by viruses.

It is convenient to think of viruses as “other.” Outsiders. Alien invaders. But they are not all that alien from the cells they infect. Viruses must have a genetic code that is recognized by the host. The viruses that infect humans carry snips of human genes, or at least some of the genetic cues for tricking human cells into doing the virus’s dirty work.

Where did these chemical pirates come from?

There are several theories to explain the origin of viruses:

Some scientists believe viruses are degenerate life-forms that have lost every animating function except the minimum genes essential to their parasitic way of life.

Or perhaps viruses evolved inside cells, as organelles, and subsequently escaped to take up their vagabond existence.

Or maybe they evolved on a parallel track to cellular life, from the simplest and earliest molecules capable of some sort of replication.

What is certain is that viruses did not evolve independently. They must constantly adapt themselves to their hosts, and their hosts must constantly struggle to stay one step ahead of them. Viral genes and host genes are stirred and restirred in a chemical mixmaster. There’s a whole lot of shakin’ goin’ on.

We may be dependent upon viruses in more ways than we know, but the equation of viruses with disease is always uppermost in our minds. They affect not only human health, but also the health of our food plants and animals. Their reputation is evil. Smallpox, chickenpox, poliomyelitis, hepatitis, yellow fever, mumps, measles, respiratory infections, rabies, warts, genital herpes, the common cold: There’s not much to like among the viruses.

And yet, and yet…

They are astonishingly beautiful.

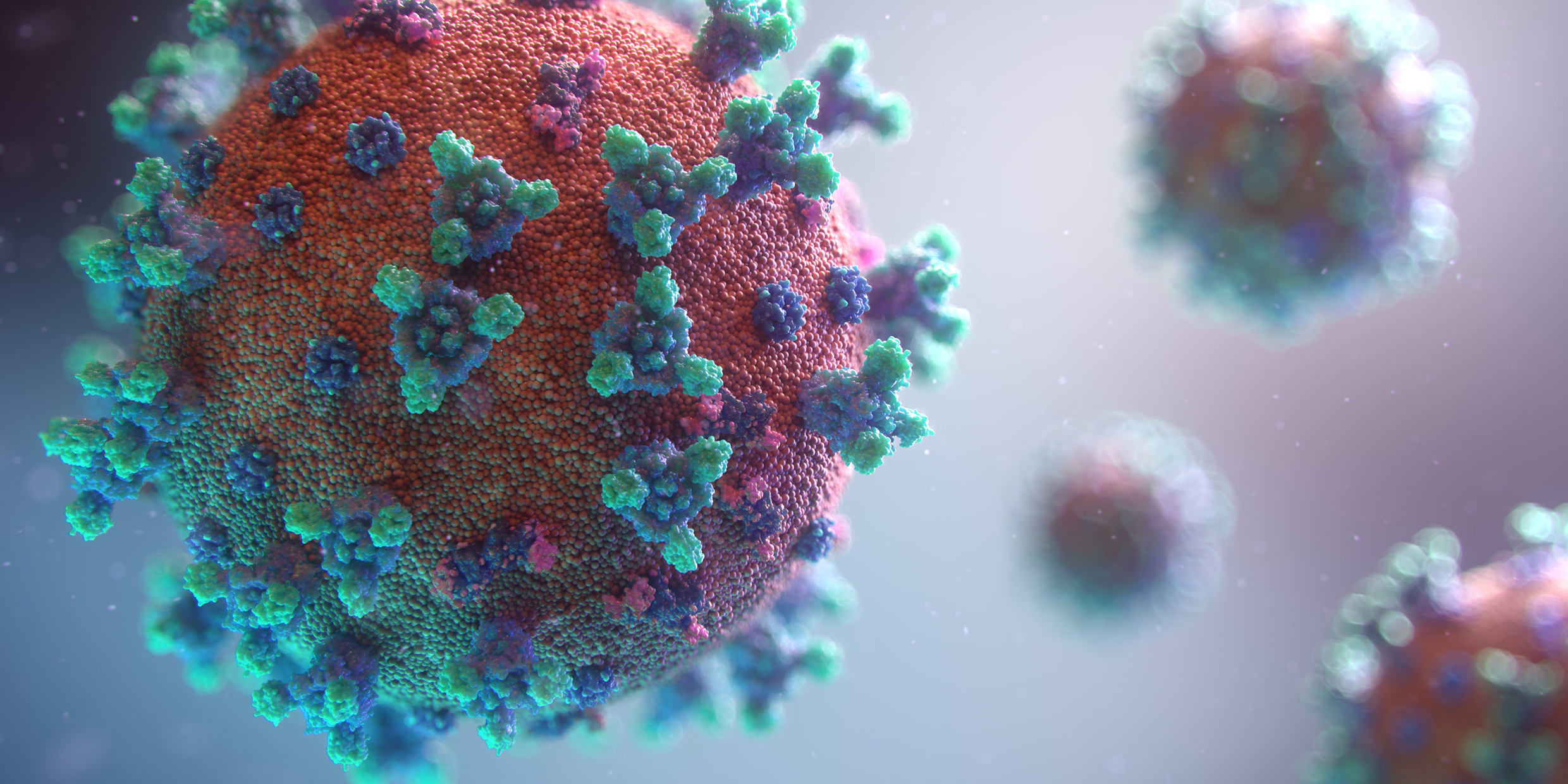

Almost every week in the science journals there is a new color-coded, computer-generated image of another virus, revealed by X‑rays and the electron microscope. These images rival the rose window of Chartres in their symmetrical loveliness. “Euclid alone has looked on beauty bare,” wrote Edna St. Vincent Millay. Euclid was a geometrician. The beauty of a virus is geometrical.

Here, at the smallest dimension of life, at a scale too small to be observed even with the best optical microscope, nature has contrived structures of stunning elegance. And not accidentally.

The beauty of a virus is a matter of necessity. A virus has only enough genes to encode for a few proteins. To build its shell, a virus must use the same few proteins over and over, like the repetitive pattern of patches on a soccer ball. For many viruses, the result is a icosahedral structure, with 20 identical triangular faces, one of the five regular polyhedrons admired by the Greeks as the epitome of beauty.

Buckminster Fuller didn’t invent the geodesic dome. Nature has been wrapping viral genes in geodesic domes since the dawn of time. And inside each dome — a single or double strand of chemical instructions saying “Build more.”

A virus is a shoestring operation, a paragon of frugality. Making do with the bare minimum, it comes up with beauty bare. Having bared some of that beauty, scientists are in a better position to counter the destructive power of viruses with drugs and vaccines.

But even with all our cleverness at frustrating their purpose, the viruses are here to stay. And maybe needfully so. If we have learned anything about life in recent years, it is that life is all of a piece. Holy and terrible, to borrow a few more words from Millay’s poem. Beautiful and scary.