Originally published 13 December 1993

Years ago, when my children were young, we lived for a year in London, not far from the famous Harrods department store. A favorite family outing was a visit to the toy department. While the kids busied themselves with dolls, trains, scooters, and skip ropes, Dad focused on the construction sets.

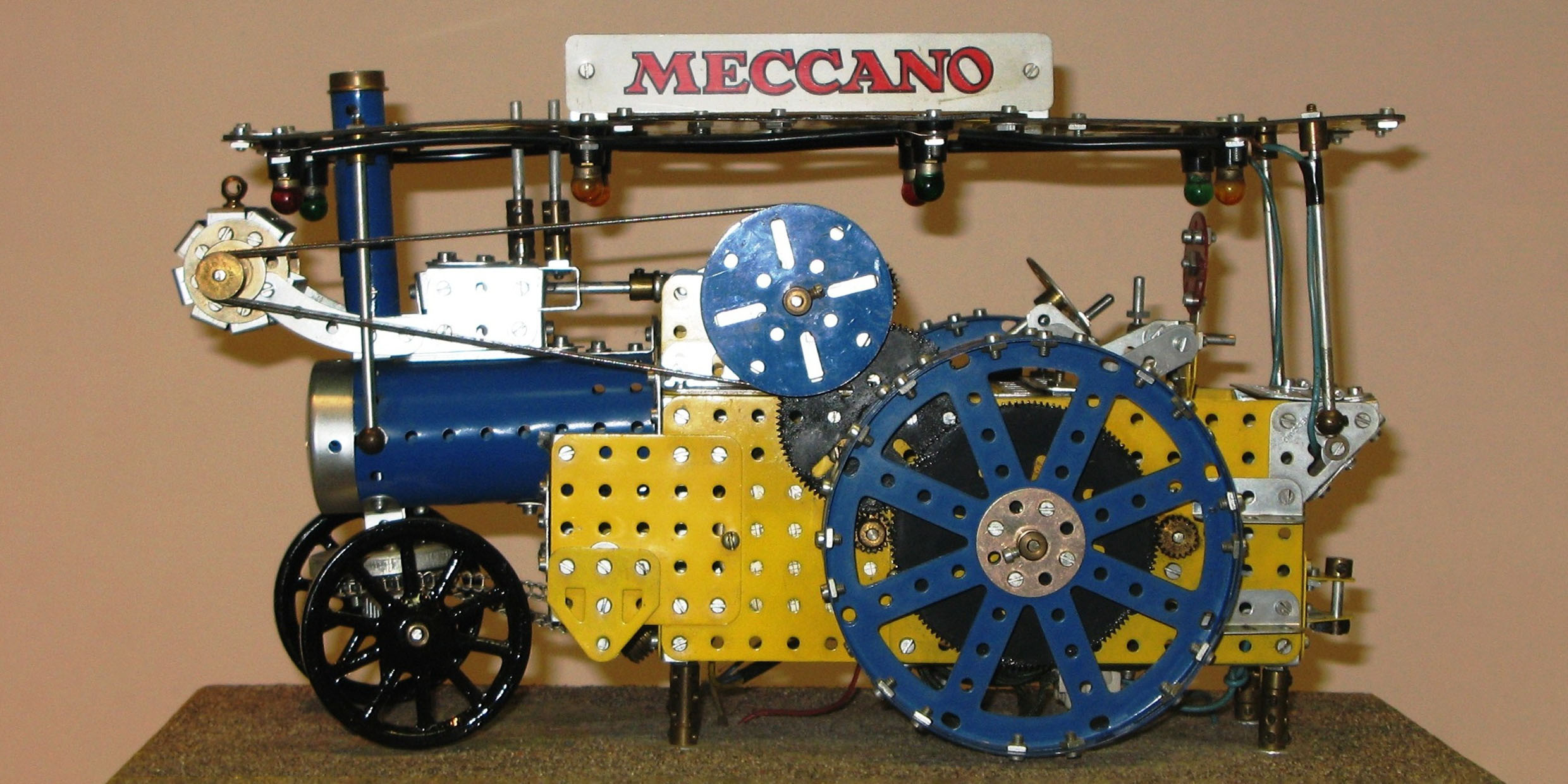

Best among them was Meccano, a French version of the American Erector set. And best among the Meccano sets was an extravagantly expensive super-set that came in a many-drawered wooden cabinet. Clearly, this thing was intended for the offspring of an Arabian prince or the playroom of Buckingham Palace.

I lusted after that Meccano set. It was the only time in my life that I wished to be embarrassingly rich.

We eventually bought the kids a starter Meccano set as a gift from Santa, and by Christmas afternoon I had it all to myself. In the British spirit, I bolted together flexible steel plates to make Cunard ocean liners, Spitfire airplanes, and articulated lorries. Of all the construction sets I have seen, Meccano yields the most realistic toys.

But realism isn’t everything. Constructions sets are stimuli for the imagination. They teach symmetry, balance, tension, compression, force, motion, energy. They plug a child’s mind into the very fabric of material creation. Even the slotted cardboard construction set I received as a Christmas gift in the war-weary winter of 1943 taught me valuable lessons in the philosophy of science.

Construction sets are a part of childhood that some of us never outgrow. Around our house you will often find adults building with whatever construction set is at hand, usually to meet some whimsical challenge. A Lego arch that spans twelve feet. A Tinker Toy cantilever that supports the weight of a book. A tower of blocks that reaches to the ceiling.

Now, it’s again the season of construction sets, and for the first time in decades I have a legitimate reason for buying: a couple of three-year-old grandchildren. So it was off to the shop at the Museum of Science to see what new developments in construction play have transpired during the past 20 years.

Erector is back as Meccano Erector in all of its nuts-and-bolts glory, after nearly disappearing into oblivion. The French company has bought the American trademark and restored the original A.C. Gilbert quality. This is still the most realistic construction set on the market. However, the old drawback remains: Erector toys are fun to put together, but tedious to take apart.

The Japanese Capsela sets are still popular. This construction toy offers interconnecting transparent plastic spheres full of gears, motors, and other mechanical and electrical gizmos. Capsela is almost too clever to waste on kids. Many a happy Christmas afternoon I spend snapping spheres together while my children mumbled to their mother “Dad won’t let us play.”

Is there a child in America who has not built with Lego? The Danish company continues to diversify. The museum shop now carries something called Lego “dacta,” ingenious kits that will give new life to hand-me-down bins of little red bricks.

If my grandchildren were older, I would buy them K’Nex. This colorful new entry in the construction set market is an ideal cross between Tinker Toy’s simplicity of assembly/disassembly and Meccano Erector’s conceptual sophistication. Thoroughly American in design and manufacture, K’Nex is a perfect excuse for becoming a grandparent.

All but the last of these construction sets appeared under our Christmas trees when my kids were young. Boxes of assorted parts still linger around the house, although many components have disappeared down the heating grates or up the hose of the Hoover. The only construction toy that remains intact is the first we ever bought: a huge set of maple blocks. These are indestructible and too big to get lost. When we bought the blocks 30 years ago, the purchase represented a substantial financial sacrifice. We have never regretted it. It is probably the best investment we ever made in our children’s education.

A construction set need not be expensive to be exciting. Some years ago our family resided for a spell in Ireland. At that time, Irish ice pops came with plastic sticks ingeniously designed with slots and notches to snap together. We picked up hundreds of these from the roadsides of our village and at no expense acquired a construction set with which to build colossal bridges and towers. One subtly-designed member, in sufficient numbers, yielded hours of pleasure.

There is more going on here than play. A good construction toy touches upon the mystery at the heart of science. The Greeks called it “the problem of the One and the Many”: How is it that a few kinds of interchangeable parts can give rise to a universe of seemingly infinite variety and complexity?

The answer can be found in a construction toy under the Christmas tree — or even in a pile of plastic ice pop sticks gathered from the side of the road.