Originally published 21 April 1986

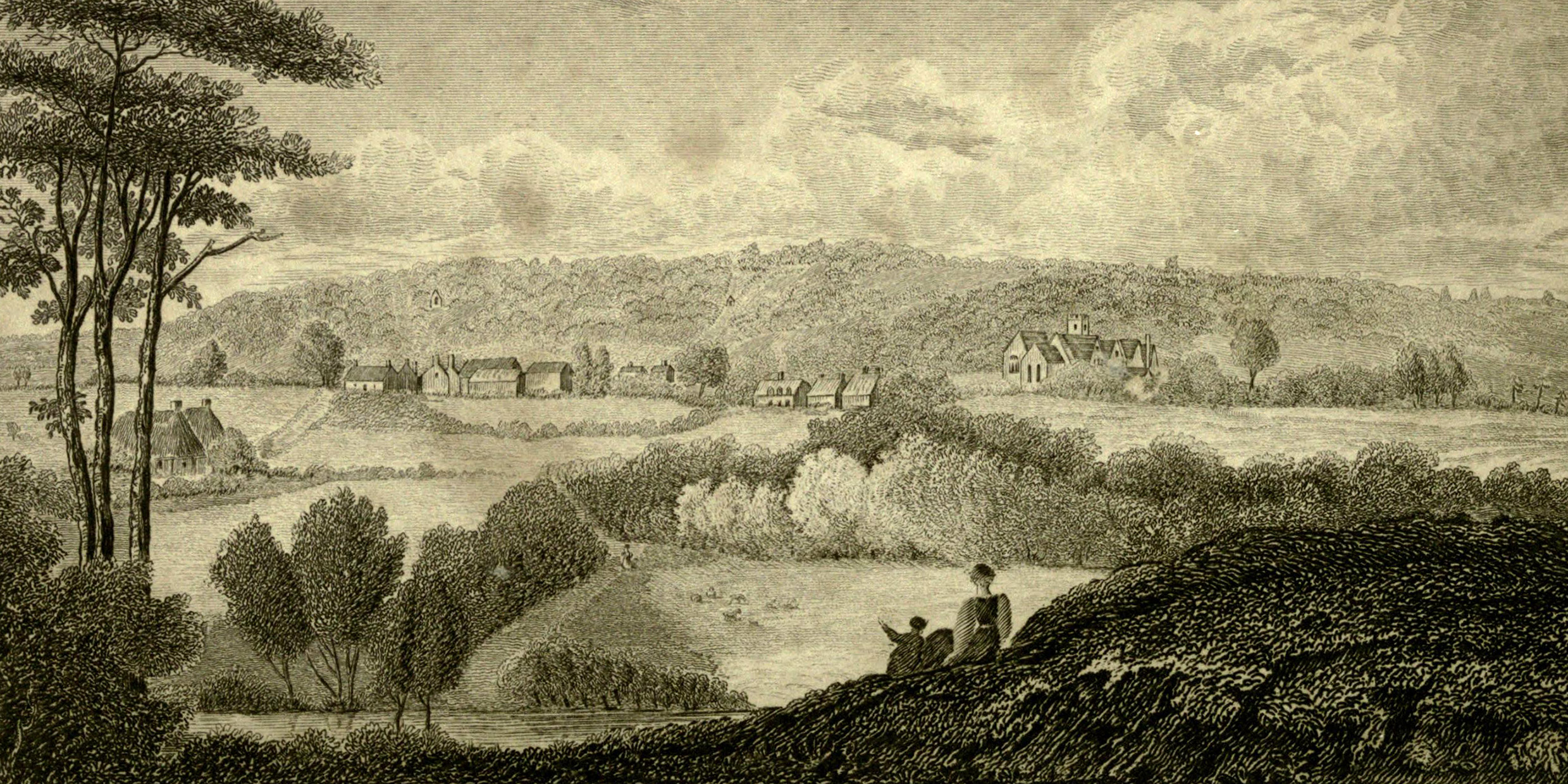

Exactly 200 years ago on this date [April 21, 1786], Gilbert White heard the voice of the cuckoo in the woods above Selborne village. Gilbert White was the curate of Selborne, a tiny village nested in a quiet dale about 40 miles southwest of London. The village has changed little since White’s day, and has become a place of pilgrimage for all who love nature.

Gilbert White might fairly be called the first naturalist. His collection of letters, The Natural History of Selborne, is the model from which many later naturalists took their inspiration.

I once had the very great pleasure of visiting Selborne. I walked through the rooms of the beautiful old house on the village green where White lived from 1730 until his death in 1793. I visited the garden behind the house, where he tended vegetables, flowers, and fruit, and where Timothy the tortoise presided. I tramped the beechwood “hanger” above the village, where White heard the cuckoo, and the path that follows the gentle brook that flows from Selborne village to the ruins of old Selborne Priory.

British conservation groups, and particularly the National Trust, have carefully preserved White’s village and the surrounding lands. To visit Selborne is to step back into history, into a simpler time, when the natural environment still pressed close upon the consciousness, and the call of the cuckoo could serve to punctuate the year.

How do I know that Gilbert White heard the cuckoo on April 21, 1786? For 25 years White kept a nature diary. In it he recorded such mundane facts as the temperature and barometer reading, and measures of wind and rain. He also entered brief observations of anything in nature that attracted his eye or mind. Those observations in the accumulation become a kind of poetry.

January 15. Hailstones in the night.

January 25. Snow gone. The wryneck pipes.

February 17. Partridges are paired.

February 21. Ashed the two meadows.

March 14. Daffodil blows.

On the title page of the volume for 1768 White copied this motto: “I solitary court the inspiring breeze and meditate the book of Nature ever open.” Gilbert White’s journals are a gentle and accurate transcription of nature’s book.

What is missing from White’s journals is almost any mention of the greater world beyond Selborne village. He lived in a time of social upheaval. The Industrial Revolution was beginning: Of this there is no hint, except for one brief reference to the weavers at Alton. There is a rebellion across the sea that will change the future. White makes a solitary note of the victory of General Cornwallis in North Carolina.

The world of Gilbert White has nearly vanished. The products of the Industrial Revolution press close upon Selborne. A drive of three miles in any direction from the village brings one back to the reality of busy highways, railroads, electrical pylons, and urban sprawl. Preserving what is left of the natural world that White so affectionately recorded will require vigilance and love.

Today is also the birthday of another great naturalist, John Muir, who was instrumental in establishing the conservation movement in this country. Muir was part of the Gilbert White tradition, as are contemporary naturalists who seek to record and preserve the natural environment.

There is a poetry in nature that is so quietly expressed that to hear it requires a special kind of silence. It is a silence that can be easily overwhelmed by the noise of machines. It is a silence we must not lose.

April 10. Therm. 72. Prodigious heat. clouds of dust.

April 12. Wheat mends. Barley-grounds work well.

April 18. A nightingale sings in my fields. Young rooks.

April 20. Some whistling plovers in the meadows toward the forest.

April 27. Many swallows. Strong Aurora.