Originally published 5 February 1996

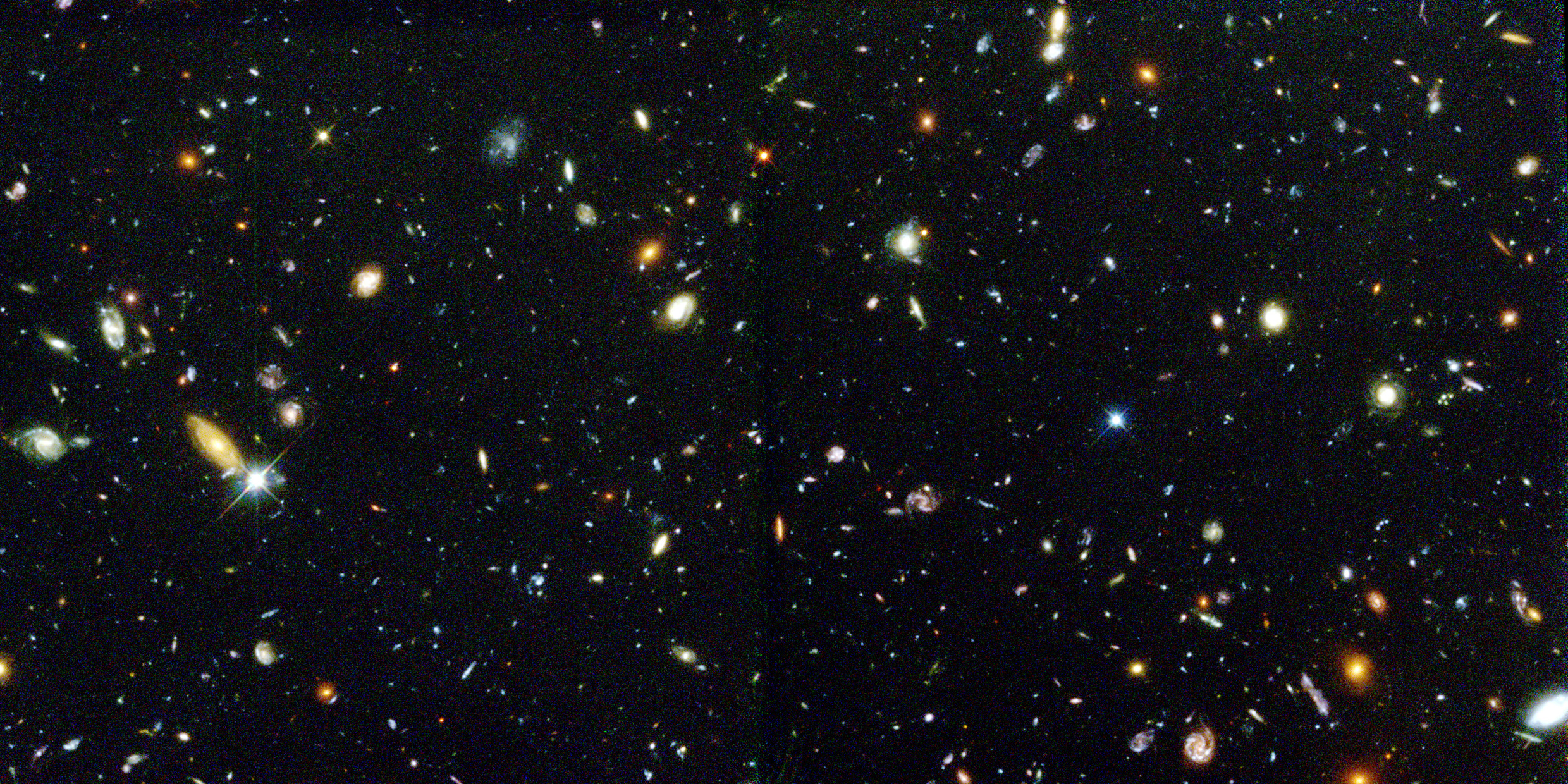

By now, you have probably seen the Hubble Deep Field photograph of the early universe. Many newspapers and news magazines have published this extraordinary image of the most distant galaxies ever observed.

The Hubble Space Telescope focused its camera on a tiny speck of sky for an unprecedented 10 days, through 342 exposures, soaking up the faint light of galaxies beyond the range of Earth-based telescopes. The result: A breathtaking snowstorm of galaxies, in living color, including relatively nearby spirals and faraway galaxies that show up as mere specks of light.

Because light takes time to reach us, when we look into deep space we are also looking back in time. The most distant galaxies in the photograph are more than 10 billion light-years away. We see them as they were not long after the universe’s beginning.

Go out tonight under the starry sky with a common pin in each hand and cross them at arm’s length. The intersection of the pins is the area of the sky shown in the Hubble Deep Field photograph.

It would take 25,000 photographs at this scale to cover the bowl of the Big Dipper.

To make the image, the Hubble Space Telescope was pointed to a part of the sky that reveals nothing to the naked eye or even to a small telescope. The field is presumably typical of what we would see if we looked any direction into the universe.

The photograph shows at least 1,500 galaxies. A survey of the Dipper’s bowl at the same level of detail would show nearly 40 million galaxies, and a survey of the entire sky would reveal 50 billion galaxies.

That’s as many galaxies as there are grains in several thousand one-pound boxes of salt. Each galaxy contains hundreds of billions of stars. Most of the stars probably have families of planets.

Our sun is just one star in the Milky Way Galaxy, a flat spiral of a trillion stars. Think of the Milky Way Galaxy as a dinner plate. The next spiral galaxy — the Great Andromeda Galaxy — is another dinner plate across the room. The nearest galaxies in the Hubble Deep Field photograph are dinner plates about a mile away. The faintest are dinner plates more than 20 miles away, at the very edge of space and time.

What is the scientific significance of the Hubble photograph? Too early to tell. Astronomers hope that by seeing deeper into space they will learn more about the earliest days of the universe, including the origin and evolution of the galaxies. They also hope to learn more about the deep structure of space and time. That’s a lot to ask of a single photograph of tiny speck of sky, but it’s a start.

For the rest of us, for the time being, the photograph expands our horizons and sharpens our sense of the size and richness of the universe. The new view of deep space shows more distant galaxies than had ever been seen before, taking us closer to the presumed epoch when the galaxies condensed out of the primordial matter.

Take another look at the Hubble Deep Field photo and then hold those crossed pins up against the night sky. Let your imagination drift away from the Earth into those yawning depths where galaxies whirl like snowflakes in a storm. From somewhere out among the myriad galaxies, look back to the one dancing flake that is our Milky Way.

Galaxies as numerous as snowflakes in a storm! When the Hubble Deep Field photo appeared in the newspapers, people came up to me and said, “Wow! It makes me feel so insignificant.”

No, no, no, I insisted, that’s exactly the opposite of what we should feel.

The Hubble Deep Field photo is a product of human imagination, the culmination of thousands of years of wondering at the night sky. It is the immediate creation of hundreds of persons, including the research scientists who analyze the data and the machinists who fashioned the nuts and bolts of the instrument.

We like to believe that the universe revealed in the photograph actually exists out there pretty much as we imagine it. But the universe of the photo also exists in here, in my mind and in your mind. We carry a universe of 50 billion galaxies in our heads, and that makes us pretty significant.

A universe of 50 billion galaxies is astonishing. But even more astonishing are those few pounds of meat — our brains — that are able to construct such a universe and hold it before the mind’s eye, live in it, revel in it, praise it, wonder what it means. A universe of 50 billion galaxies blowing like snowflakes in a cosmic storm is astonishing, but not nearly so astonishing as the human brain.