Originally published 20 December 1993

A still November morning. Brittle, transparent, like glass. Suddenly shattered.

Not 50 feet in front of me a huge bird labors into the air, a gray burden in its talons. Push, push, push — gaining altitude. Coming to rest on the branch of a pine.

A red-tailed hawk.

I slip my binoculars from my bag and focus. The hawk sits upon a plump cushion of feathers. I move closer until I see that the cushion is a pigeon, not dead but terrified into stillness.

I have witnessed something primal, unpretty, true. Nature red in tooth and claw. The bloody engine of evolution.

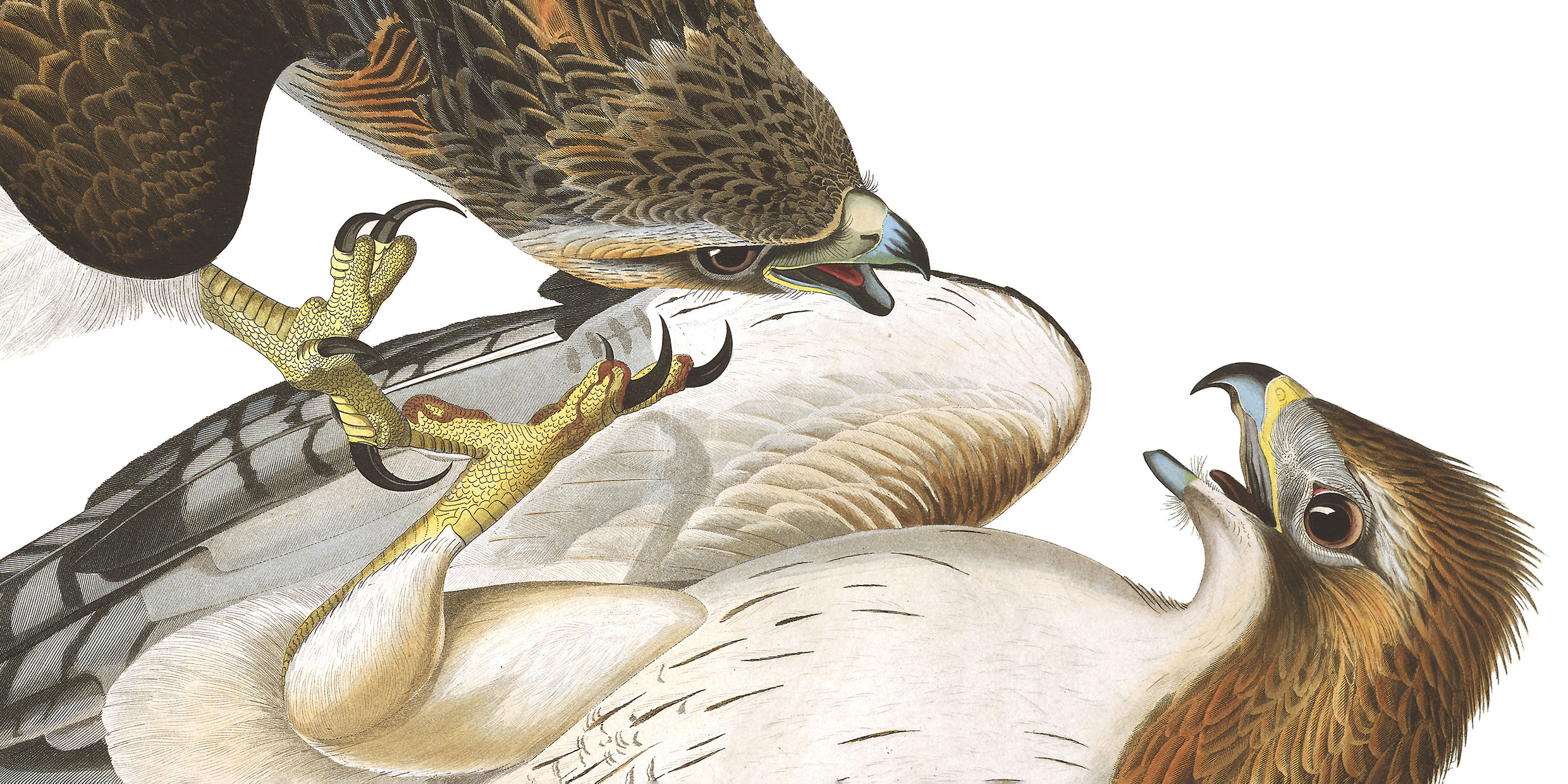

A few days later I am in Washington, visiting the National Gallery of Art’s exhibit of John James Audubon’s watercolors for The Birds of America. Here among a peaceable kingdom of warblers, vireos, and wrens are male and female red-tailed hawks, caught by Audubon’s brush in mid-air, the male’s wings swept back, his talons tearing at the female, seeking to snatch from her the frightened hare in her claws.

The painting was done in Louisiana in 1821, not long after Audubon witnessed the airborne battle.

The postures of the birds show their plumage to best ornithological advantage. We are given the male bird’s back, the female’s breast. The beaks are rendered in profile and from the top. The red tail feathers are shown from above and below.

It was Audubon’s genius that he was able to combine lively story-telling with accurate scientific description. It is the source of our enduring fascination with his art.

Audubon refused to prettify nature or soften its apparent cruelty. The hare in the female hawk’s talons can almost be seen to shiver and whimper with fright. Its belly is streaked with blood and urine. This harsh realism is also part of our fascination with Audubon.

When the artist arrived in Edinburgh, Scotland, looking for a printer for his work, he showed his watercolors to the engraver William Home Lizars. Lizars was immediately drawn to the paintings depicting violence in nature: Mocking-birds attacked by a rattlesnake, a hawk pouncing on 17 partridges, and a whooping crane eating newly-born alligators. He finally decided to begin his work with great-footed hawks, “with bloody rags at their beaks’ ends and cruel delight in their daring eyes.”

Audubon was a woodsman. He shot his birds to paint them. He experienced daily the hard continuum of violence that links us with the other beasts. He also participated in several incidents of violence of a kind that separates us from the rest of nature.

In Kentucky, in 1813, a billion passenger pigeons came to roost in a forest on the banks of the Green River. Farmers traveled hundreds of miles to greet them. They came with wagons packed with guns and ammunition. Audubon was there. His description of the ensuing slaughter is chilling.

During the course of one long night, uncountable numbers of the birds were shot with guns or simply beaten from the trees with poles, each man taking as many birds as he had provision to carry. Hogs were let loose to feed upon the considerable remainder. The carnage vastly exceeded any need for food.

Later, Audubon participated in a buffalo hunt on the Great Plains, a prodigious and terrible taking of life. After shooting his first bull, he cut off the tail and stuck it in his hat. Other hunters smashed open the skulls of animals and ate the brains, warm and raw.

The great ornithologist experienced a twinge of remorse. He wrote: “What a terrible destruction of life, as if it were nothing, or next to it, as the tongues only were brought in, and the flesh of these fine animals was left to beasts and birds of prey, or to rot on the spots where they fell.” He feared lest the buffalo should go the way of the great auk, a North American bird that had previously existed in great numbers, but already in Audubon’s time had been driven to extinction by human wantonness.

Among Audubon’s watercolors at Washington’s National Gallery there are many of sweet tranquility and gentleness: I was drawn especially to the sad, wise face of the great gray owl, and the great egret with a tail like a flow of water. But I came back again and again to the red-tailed hawks engaged in the bloody battle for the hare, perhaps because they reminded me of the taking of the pigeon I had witnessed only a few days earlier.

Violence is part of nature, neither moral nor immoral. It is only to acts of human violence that we apply ethical judgments. Most of us do not fault Audubon the use of his gun on behalf of his art and science, but we shrink from the unrestrained slaughters of pigeons and buffaloes of which he was a part.

The passenger pigeon is extinct. The buffalo survives but barely. Since Audubon’s time, many dozens of species of birds, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and fish have been driven to extinction in the United States. The slaughter of innocents continues. It is a kind of violence that in all of nature is uniquely human.