Originally published 21 October 1985

In his autobiographical book The Double Helix, James Watson, the co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, tells how he came to think of the helix as the fundamental structure for that molecule.

“The idea (of the helix) was so simple,” he says, “that it had to be right.” I thought of Watson’s words today as I looked through the October [1985] issue of Scientific American. The issue is devoted to the molecules of life, and it is illustrated with stunning computer-generated images of DNA, ATP, proteins, hormones, and the other molecules that make us go.

The molecules of life are complex — they are made up of thousands, billions of atoms — and yet they are so simple and so beautiful that we look at them and we know that they are right.

Molecular biologists often build models of the molecules of life with sticks and plastic spheres. But the computer images are more striking than any mechanical model I have seen. On the computer’s screen the molecules can be turned, twisted, mated, and modified. One can literally watch as, for example, an antigen binds itself to an antibody, a central event in the body’s recognition of a foreign organism. And the computer can represent many more atoms than can be reasonably incorporated into a model made of balls and sticks.

Complexity and simplicty

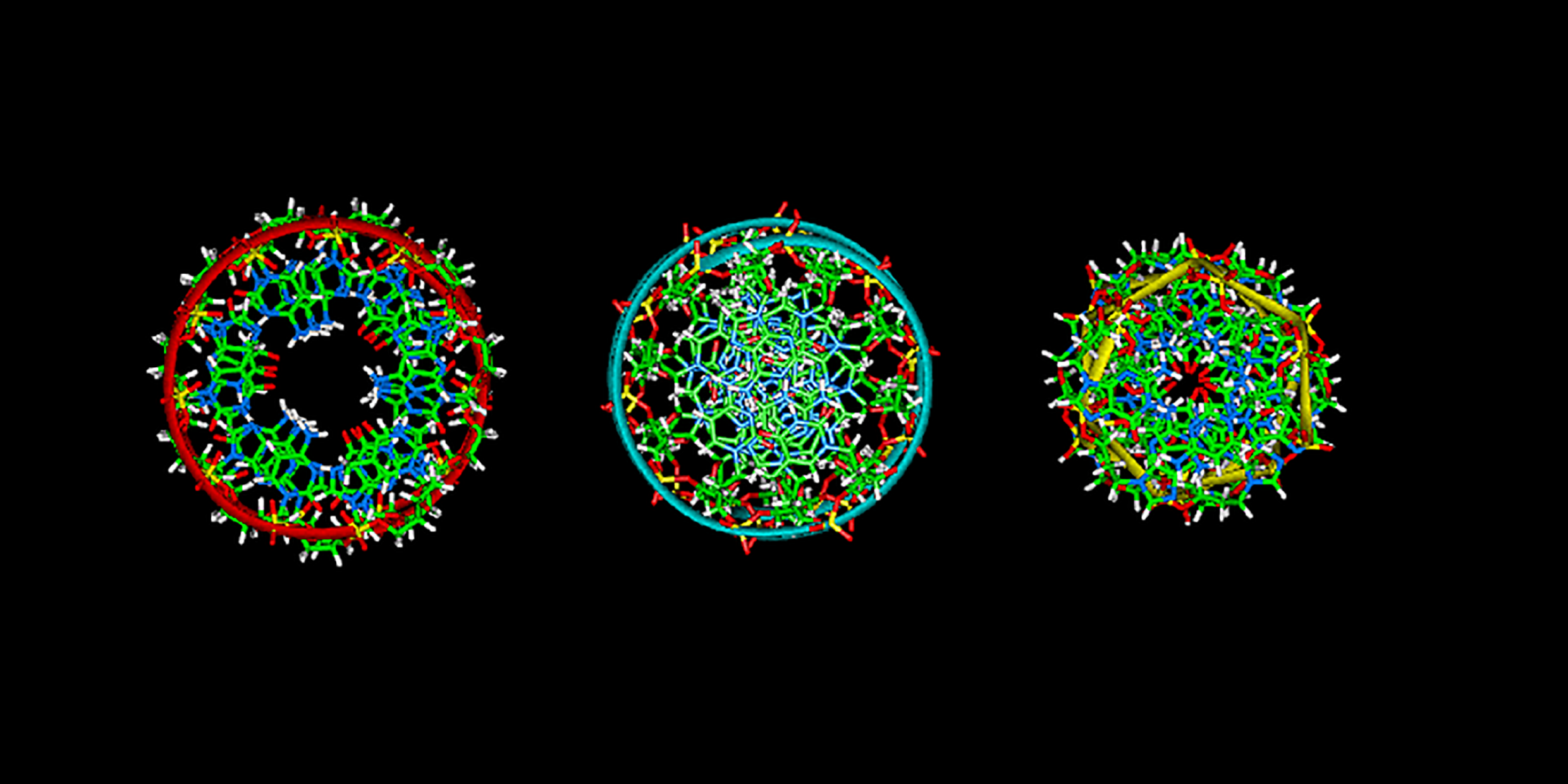

If I focus on the “atomic” dots of these computer images, I am bewildered by the astonishing complexity of detail, and I wonder that life exists at all. But when I focus on the overall patterns — the geometrical forms and symmetries of the molecules — I am dazzled by an almost inevitable simplicity. Every molecule seems miraculously contrived for its task. The molecules of the computer images glow luminously against black backgrounds, with each atomic element shimmering in its own color.

As I studied the images, I had the feeling that I had seen them before. And then I knew what it was that I was remembering — the gorgeous stained glass windows and soaring architectural members of the Gothic cathedrals. An image of the B DNA double helix in cross-section bore an astonishing likeness to the magnificent rose window at Chartres. And in the webbed vaulting of the clathrin protein and the flying buttresses of the sugar-phosphate side chains of the DNA I had that same sense of déjà vu.

No medieval architect could have raised more fitting structures. The medieval builders wanted to reflect in the visible structures of the Gothic cathedral the invisible realities of the world of spirit. The cathedral was conceived as an earthly image of the kingdom of God.

Hidden harmonies of nature

Something similar is afoot in these computer images of the molecules of life. Here, too, there is an attempt to represent an unseen reality with visible images. And here, too, there is an almost mystical vision of a hidden harmony that has been established throughout the cosmos.

When we enter a Gothic cathedral we have the sense that every visible member of the structure has a job to do. The Gothic architects achieved a unity of function and form that has seldom been surpassed.

The molecules of life express that same unity. One of the Scientific American images shows the Cro repressor molecule affixing itself to the DNA helix of a bacterial virus; the Cro repressor acts to prevent the expression of a gene, and thereby exerts a tiny but significant twist to the thread of life.

On the screen of the computer the two molecules come together and mate like lock and key. No atom appears to be in excess. Nothing is wanting. It is said that medieval theologians debated about how many angels could dance on the head of a pin. The glissades and pirouettes of the antigen and the Cro repressor, and the whirling tarantella of the DNA double helix as it unwinds to copy the genetic code, are movements as delicate and lovely as the dance of any angel. The computer makes visible this hidden choreography. And the number of these molecules that could fit on the head of a pin is astronomical.

Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis, one of the first great Gothic builders, hoped that his cathedral would reveal the divine harmony that reconciles all discord and would inspire in those who beheld it a desire to establish the same harmony within the moral order. It occurred to me that the images of the molecules of life achieve the same effects. They inspire a reverence for the invisible harmony — of form and function, of complexity and simplicity — that is the miracle of life.

And they instill the hope that we are wise enough to treat all life as precious.