Originally published 26 March 1990

Baily’s beads, Barr body, Beaufort wind scale, Bernoulli effect, Bessel function, Bessemer converter, Boolean algebra, Bose statistics, Brewster’s law.

Some or all of these terms will be familiar to every scientist. But who were Baily, Barr, Beaufort, and the rest?

Time to get out the Chambers Concise Dictionary of Scientists, (W & R Chambers and Cambridge University Press). These names are there, and more — 1,000 scientists to be exact. According to the authors, the 1,000 most important scientists of all times.

They include men or women whose names are famous in the sciences or mathematics, often because laws, units, effects, chemical reactions, diseases, or mathematical methods have been named after them. Thus, Baily, Barr, Beaufort, Bernoulli, Bessel, Bessemer, Boole, Bose, and Brewster.

There are other criteria for inclusion. Winning the Nobel Prize is not sufficient to gain entry to the list, but it doesn’t hurt. What is required is a contribution to the “body of well-received scientific knowledge which still, despite challenges, survives.”

Any such list is bound to be subjective. Everyone who picks up the book will know someone who should have been included and wasn’t. Where, for example, is Rosalind Franklin, who made important contributions to discovering the structure of DNA? Where is Asa Gray, one of the most influential American biologists of the last century?

Whatever its shortcomings, the Concise Dictionary of Scientists is fun to peruse and a lively introduction to the history of science.

Starts with the Greeks

The earliest scientist in the dictionary is Thales, who lived in the 6th century B.C.. He is recognized for offering natural rather than supernatural explanations for phenomena such as earthquakes, and for insisting that theories be derived from observed facts.

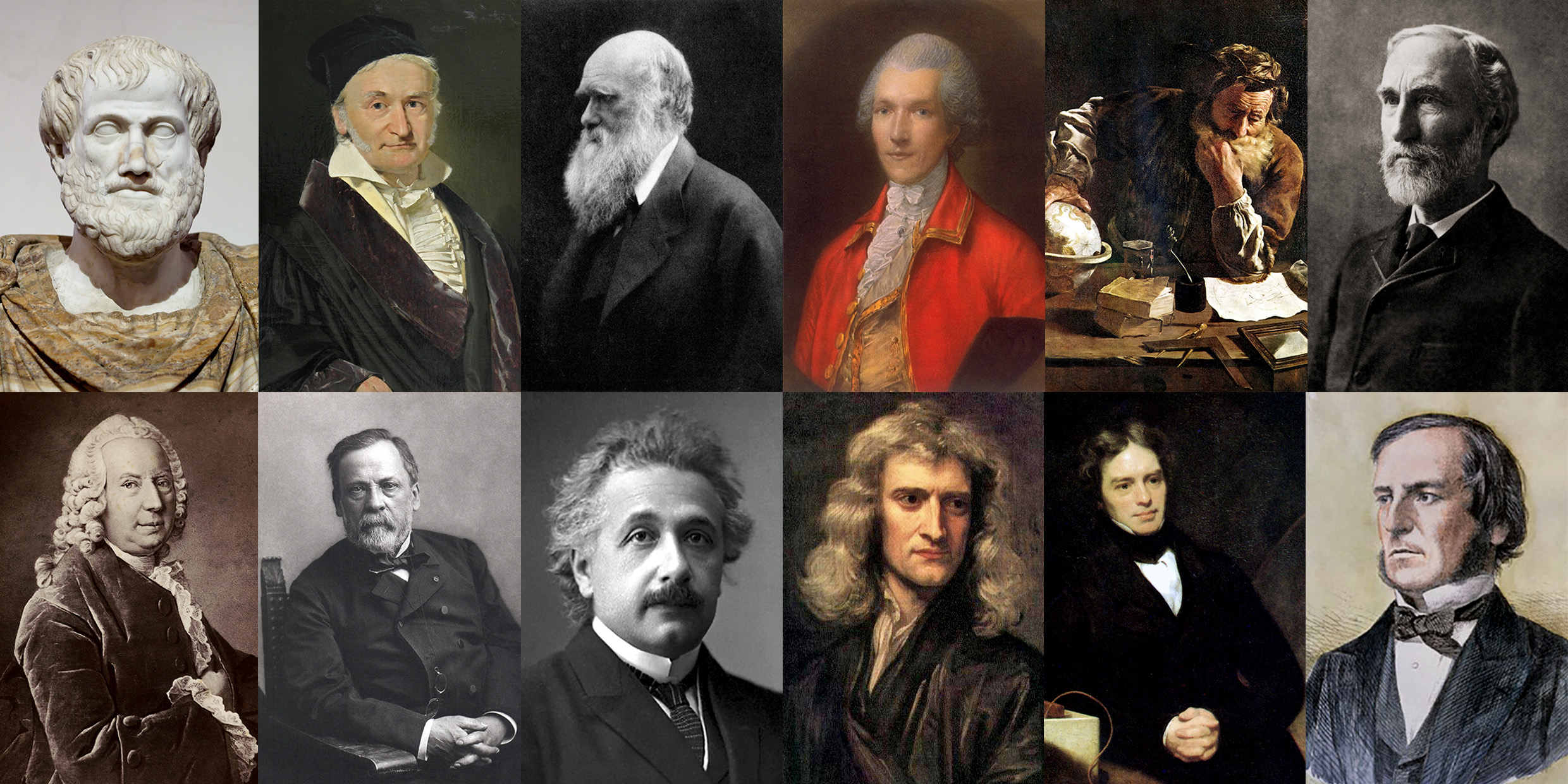

The A’s especially are full of classical Greeks—Anaximander, Apollonius, Archimedes, Aristarchus, Aristotle—and appropriately so. It has been said that science is nothing more than thinking about the world in the Greek way. During Europe’s Dark Ages, Greek science was kept alive by Islamic scholars, and that period is reflected by a smattering of Arabic names in the dictionary.

For the next few centuries all entries in the dictionary are European. Scientists from the Indian subcontinent enter the tradition with the British raj, and Japanese and Chinese physicists make a strong showing in the mid- and late-20th century. By my count, about 20 percent of the “1,000 greatest scientists” are alive today.

Only 15 women are included in the dictionary, suggesting that half of human genius has been excluded from participation in this great enterprise. All of the included women made their most significant contribution within the last century.

By nationality, the British dominate — about one-quarter of the list — followed closely by Americans. One wonders to what extent these numbers reflect the fact that the dictionary’s four authors are British. Certainly the American list is swelled by the large number of scientific expatriates who came to our shores around the time of World War II.

Given the cumulative nature of science, one might guess that the chronological distribution of entries would be a rising curve peaking in our own time. Not so. I counted as many 19th century scientists as 20th century scientists, a fact both surprising and significant.

Physics, chemistry, biology, astronomy, and geology all took their basic outlines in the 19th century. Most 20th century contributions occur at the interfaces of the older disciplines — biochemistry, geophysics, physical chemistry, and so on.

Isaac Newton gets the largest entry in the dictionary (slightly more than two pages), followed closely by Albert Einstein. Other space-grabbers are Faraday, Pasteur, Darwin, Maxwell, and Gauss.

Mere fame does not warrant a generous entry. Immanuel Kant would surely dominate a dictionary of philosophy; here he gets only a brief mention for his nebular hypothesis for the formation of the solar system.

Josiah Willard Gibbs, the 19th century physical chemist from Yale University, is described as “probably the greatest theoretical scientist born in the US.”

Massachusetts scientist included

The longest entry for a scientist from the Boston area goes to Count Rumford, born Benjamin Thompson in Woburn in 1753. Thompson measured the relation between heat and work, a crucial step on the road to the Principle of Conservation of Energy.

He began his career by marrying a rich New Hampshire widow, and ended it as a count of the Holy Roman Empire. Along the way, he fought for the British in the American Revolution and was rewarded by George III with knighthood. He served as a social and educational reformer in Bavaria and confounded Britain’s Royal Institution, the scientific center where Davy and Faraday performed their important experiments. He was friend to Napoleon and second husband to Madame Lavoisier, wife of the famous French chemist. Rumford’s scientific accomplishments were considerable, but the size of his entry is inflated by the astonishing facts of his flamboyant life.

The Britons who compiled the Concise Dictionary are David Millar, a geophysicist; Ian Millar, and organic chemist; John Millar, a theoretical physicist, and Margaret Millar, a secretary and research assistant.

Their task was complicated by the highly specialized nature of much contemporary science, which makes it difficult for non-specialists to judge relative importance. Further, the high cost of “big science” has led to extensive team work, so that it becomes almost impossible to select key individuals in the traditional manner. “It may be very difficult to write a book such as this in the 21st century,” the authors conclude.

For the time being, however, they clearly had a good time making their choices and writing lively snapshot-biographies. What they have produced is an entertaining and useful family album for science.