Originally published 9 January 1984

The ingredients of life on Earth were collected by gravity. The hearth that held the tinder and received the spark of life was a small heavy-element planet near a yellow star. Chemistry was the steel and time the flint that struck the spark. For the spark to catch and the flame to grow required not biblical days, but hundreds of millions of years. The solar system has been around for four and a half billion years. That’s time enough for miracles.

One day last summer within the span of a few hours I vividly experienced the wealth of time allotted to life on Earth. In the morning I walked on Inch Strand, a promontory of yellow sand that nearly closes Dingle Bay in the west of Ireland. The tide was out and the sand bars were corrugated with ripples. In the afternoon I was on the summit of Carrantuohill, the highest peak in Ireland. On the shoulder of the mountain, three thousand feet above the sea, I stood beside a vertical slab of sandstone, marked with the very same corrugated ripples I had seen at the edge of Dingle Bay.

Buried ripples

My geology map of Ireland tells me that the sandstones on Carrantuohill date from the Devonian era, 400 million years before the present. Four hundred million years ago the tide rippled a Devonian beach. The ripples were buried by more sand before they were washed away. Successive layers of sediment covered the ripples ever more deeply. Ultimately the sediments were turned to stone and lifted into a high range of mountains. Then erosion pared the summits down, grain by grain, exposing at last the ancient rippled beach that had been so long hidden in the heart of a mountain.

Four hundred million years for the sandy ripples to make their way from the edge of the sea to a mountaintop! What is four hundred million years to a creature who measures life in hours and minutes?

It was James Hutton, gentleman farmer of Scotland, who taught us how to look backward along the giddy spiral of time and see more than the several thousand years that had been allotted to the Earth by biblical history. Hutton’s Theory of the Earth, read before the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1785, conferred upon the planet sufficient time for nature to raise up mountains and tear them down without the agency of specific and recurring divine intervention. As he studied the rocks of his native Scotland — among them the same Devonian sandstones I found on Carrantuohill — Hutton saw in his mind’s eye the beaches that had been buried and turned to stone, and the mountains that rose and fell like waves on the sea. He saw, he said, “no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end.” Hutton’s gift to science was the gift of time, geologic time, rock time, time in which all of human history was but the tick of a clock.

Reading the rocks

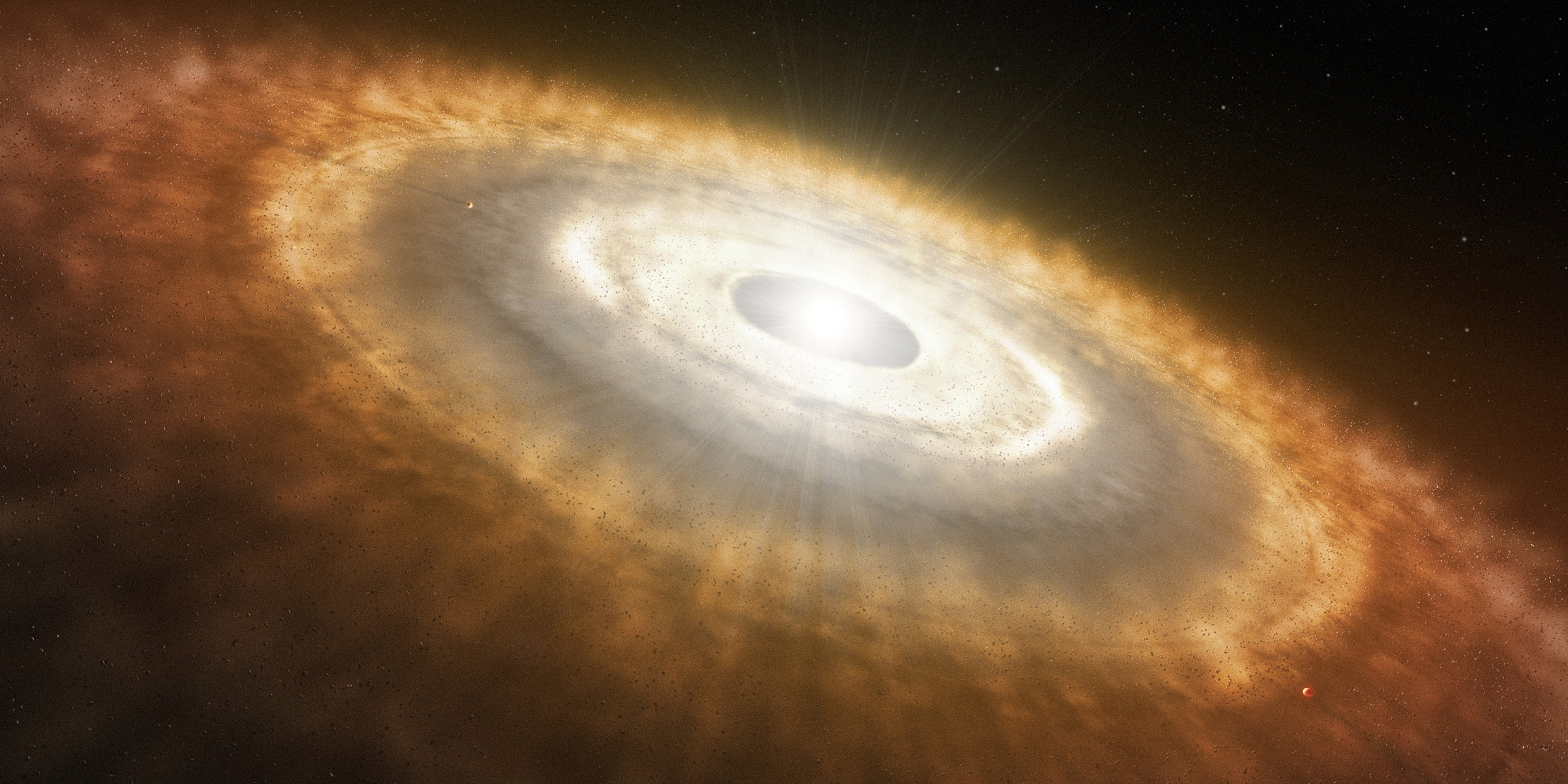

Armed with Hutton’s notion of geologic time, we turn to the record of the rocks. Far back in the annals of the former world (Hutton’s phrase), on the first page so to speak, we read of the formation of the earth from the dust of space. Mystery and controversy surround the Earth’s beginnings, but virtually all astronomers and geologists agree on the central plot. The Earth, the Moon, the sun, and the other planets condensed together from a cloud of interstellar dust and gas. The cloud was mostly hydrogen and helium, but contained a smattering of heavier elements like carbon, silicon, oxygen and iron. It was gravity that pulled the cloud together. Gravity is the elastic which pervades the universe and —unopposed — causes everything to fall into clumps.

The nebula which became the solar system had some small degree of rotational motion. As the nebula compacted it began to rotate more rapidly, as an ice skater spins more rapidly as he draws his arms close to his body. As the cloud spun faster it flattened out, as pizza dough flattens when twirled by a chef. The flattened disk of dust and gas became the solar system.

Most of the matter in the flattening cloud was pulled to the center of the disk and became the sun. Gravity continued to squeeze that central sphere, and the temperature at the core of the sun soared to millions of degrees. Thermonuclear reactions were triggered and a new star — our star — turned on in a blaze of glory.

Meanwhile, in the spinning disk, the heavier atoms and molecules condensed to form dust-sized grains. As time passed, these metallic and rocky grains in the inner part of the disk clumped together into asteroid-sized bodies, and these in turn collected by collision and the pull of gravity into the early planets. At some point in this process, the sun turned on with a sudden violence that swept the inner solar system clean of the lighter leftovers. Whatever light gases clung to the inner planets were blown away.

All of this took place four-and-a-half billion years ago.

There is considerable controversy about what happened next. Perhaps the Earth had a cold beginning, growing like a big dirty snowball from clumps of whatever materials had condensed at the Earth’s distance from the sun. Or perhaps the Earth was hot at its birth and there was some layering of materials even as the planet formed. In any case, the planet soon heated up, melted, and sorted itself out by density, with the heaviest materials sinking toward the center and the lightest materials rising toward the surface. Within half-a-billion years of its formation, the earth was physically similar to the earth today. It had a metallic core, a rocky mantle and a crust that had cooled sufficiently to provide a solid platform for the great experiment of life.

In such a way was the hearth prepared for the spark of life. In a sense, the outcome of the story was inevitable. Every atom in the universe is imbued with that attractive quality called gravity. Every atom has the chemical propensity to link up with other atoms in ways which lower the energy state of the combination. Even in its tiniest grain, the universe is quickened with a drive toward consolidation and complexity. All that was required for the creation of a star, an earth and ultimately life was time, geologic time, the time of the rocks on Carrantuohill, time without vestige of a beginning or prospect of an end.