Originally published 20 April 1992

The golden age of anthropology is past. The time is gone when a Gregory Bateson or Margaret Mead could go off to New Guinea or Samoa and find societies relatively untouched by Western civilization. An anthropologist today is hard pressed to find a culture anywhere on earth that retains its original traditions and values. One is as likely to find Coca-Cola and satellite television in the wilds of New Guinea as in New Jersey.

So what’s an anthropologist to do? Well, he can seek out some idiosyncratic subset of global society as his subject. Thus do we get anthropological studies of corporate executives, teenage “mall rats,” and New York taxi drivers. Surely, the toughest part of such work is finding something original to say about a group of humans that may be substantially like the rest of us.

This plight of contemporary anthropologists came to mind as I read Sharon Traweek’s Beamtimes and Lifetimes, a study of high-energy physicists (the scientists who use huge accelerating machines to smash up sub-atomic particles and discover laws of matter). The book has just been issued in paperback by Harvard University Press.

Traweek is a professor of anthropology at Rice University. Her research was done at three high-energy research labs during the 70s and 80s. These were the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) near San Francisco, the Fermi National Accelerator Lab near Chicago, and the National Laboratory for High Energy Physics in Japan.

The community of high-energy physicists is worthy of serious study. These people are the self-appointed elite of scientists. They possess the biggest machines, the biggest budgets, and some of the brightest minds. They profess to seek the ultimate laws of the universe. They speak a language absolutely no one else understands.

A chance squandered

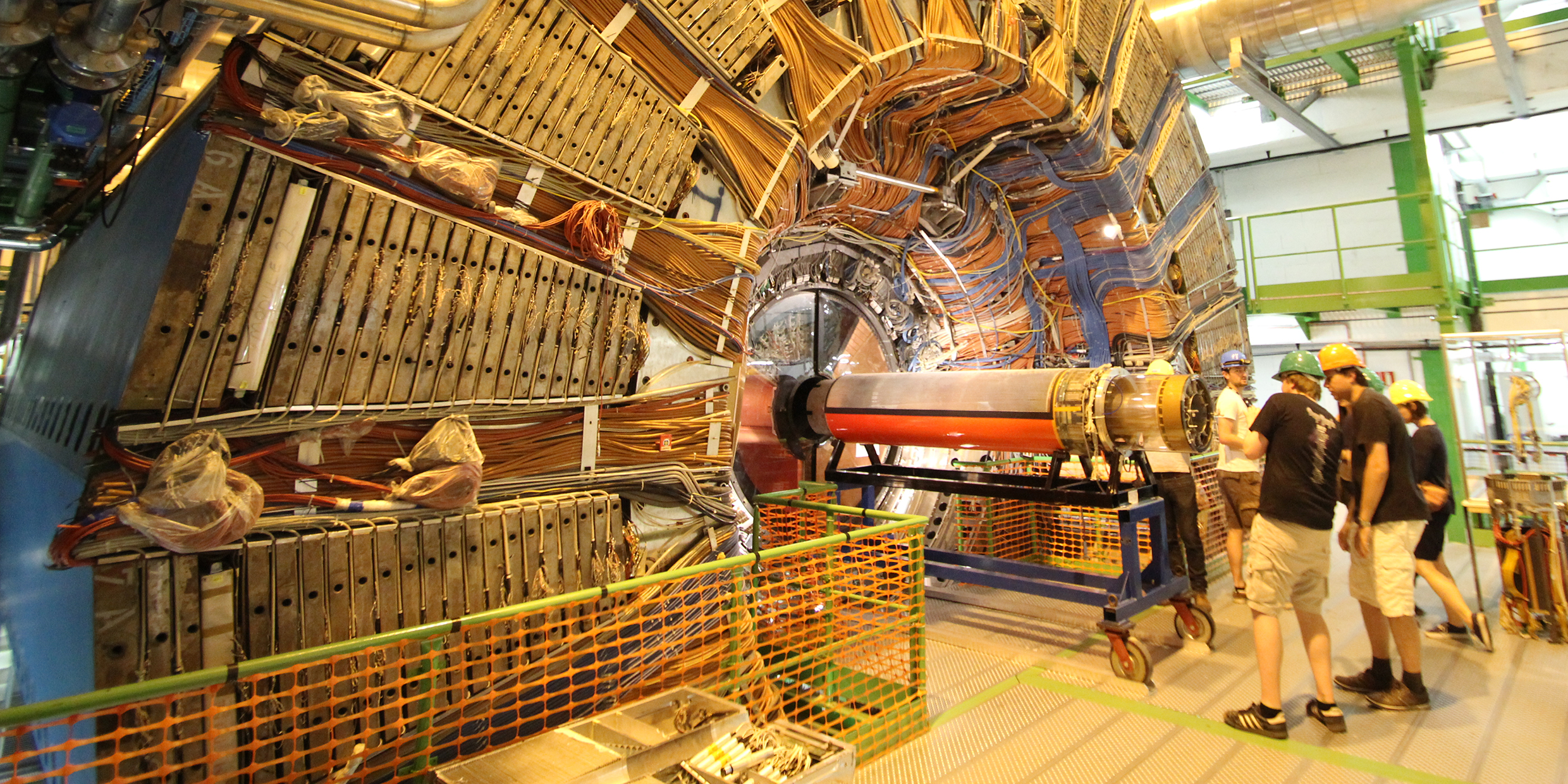

High-energy physicists share a history, a mythology, a cosmology, a highly-stratified social hierarchy, and unique artifacts (multi-billion dollar accelerators) — everything, in short, to qualify as apt and interesting subjects for anthropological research. Alas, although Traweek comes tantalizingly close to illuminating some serious themes, she squanders her authority with dubious theories and anecdotal evidence.

She is at her best when she describes the progress of a high-energy physicist from graduate student, to postdoc, to group leader, to lab administrator, to Nobel laureate. She captures a sense of the intense competition, the rigorous weeding out of lesser talents, the quest for “beamtime” (a chance to use the big machines for experiments), and — last but not least — the driving need to possess the most energetic accelerators on Earth. It is one of the ironies of nature that to understand how the tiniest particles of matter were forged we must recreate in accelerating machines the stupendous energies of the Big Bang.

Traweek is less convincing when she tries to tell us what all this means. No one will dispute that high-energy physics is a mostly male enterprise and probably impaired by the flaws of that gender, but Traweek stretches our credulity when she describes the relationship between the scientist and nature as sexual.

She professes to see genital imagery in the acronyms SPEAR and SLAC. It is hard to imagine that the persons who named the Stanford Positron Electron Asymmetric Rings and the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center consciously or unconsciously had these mutually annihilating associations in mind. She observes that the Large Aperature Solenoid Spectrometer is called LASS, and assures us that a glance at the magnets of this machine would confirm the “labial” imagery. She sees significance in the physicist’s description of the beam (the stream of accelerated particles) as “up” and “down” (on and off).

According to Traweek, the physicist imagines himself as desiring male and nature as female. Detectors — the giant spark chambers and bubble chambers used to record particle collisions — are the site of their coupling. She writes: “Standing on the massive, throbbing body of the eighty-two-inch bubble chamber at SLAC while watching the accelerated particles from the beam collide twice a second with superheated hydrogen molecules made this [sexual imagery] quite clear to me…The consummation of the marriage between scientist and nature in the detector sometimes leads to progeny for the proud scientist: a discovery, attesting that he is a real scientist.”

So much silliness

Oh, dear. If Traweek got it right, then high-energy physicists should blush with embarrassment. If she got it wrong, then she got it very wrong indeed.

What is missing from Traweek’s study of high-energy physicists is what physicist Victor Weisskopf calls the “joy of insight.” In her concentration on “genital” detectors and a supposed “coupling” between scientist and nature Traweek minimizes a mysterious interplay of mind and nature that goes beyond metaphors of seduction or rape. With hugely-complex machines of human invention, high-energy physicists probe the interiors of protons and the first split seconds of creation. Their motive is curiosity about the fundamental architecture of nature; their reward is not some macho turn-on but understanding.

What is also missing from Traweek’s study is a sense of what high-energy physics means for the rest of us. Surely to discover how and when the universe began, of what it is made, and why it works the way it does, is a task worthy of societal support. To describe this glorious adventure as so much cave-man posturing is not only silly, it demeans intellect and imagination.

When originally published in 1992, this essay prompted a lively discussion among the readership, concerning sexism in language and gender inequality in science. You can read Chet’s followup to this discussion. ‑Ed.