Originally published 15 May 2005

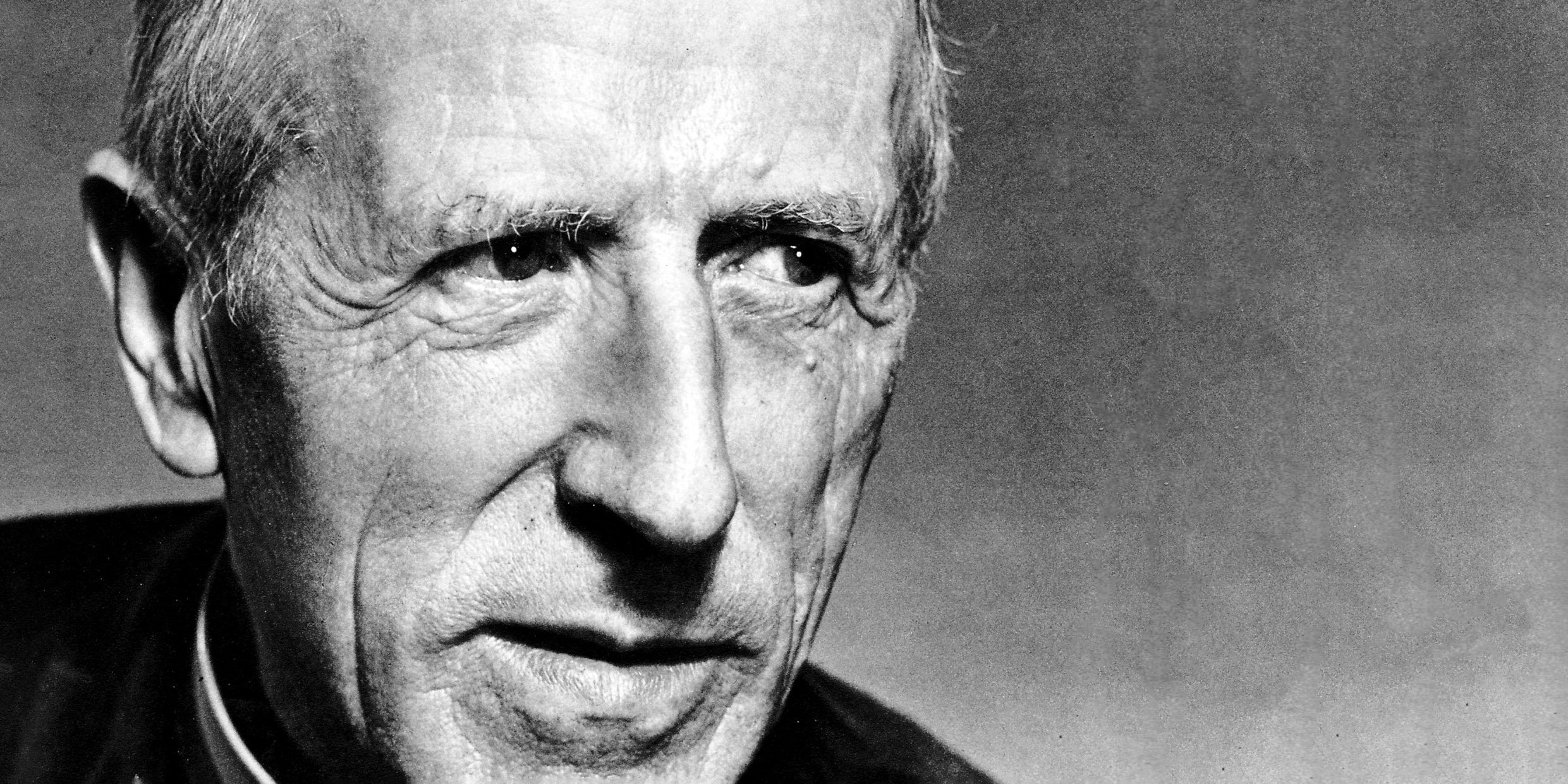

In the beginning, there was not coldness and darkness: There was the fire,” wrote the Jesuit anthropologist Teilhard de Chardin in The Mass on the World.

He added, “The flame has lit up the whole world from within…from the inmost core of the tiniest atom to the mighty sweep of the most universal laws of being.”

It has been 42 years since I first read those words. I was then a graduate student in physics at the University of Notre Dame, discovering a world of matter, energy, and natural law, and struggling to accommodate my new learning with the Roman Catholic faith of my youth.

Teilhard de Chardin came into my life like a blaze of light. Here was a man, a Catholic no less, who sang the wonders of matter and energy, who turned the evolution of the universe into a theology of praise.

I was not alone in my admiration for the lanky, enchanting Jesuit; many of my generation were caught in his spell. We were hungry for a way to reconcile science and spirit. Teilhard offered a vision of a world shot through with mystery and meaning — an animating fire that could only be perceived with the scientifically-informed eye of faith.

Then, in 1965, only a few years after Teilhard’s works became available in English, physicists discovered the cosmic microwave background radiation, the all-pervasive afterglow of the Big Bang. The “steady state” theory of the universe was tossed. In its place, we were offered a universe that began as a speck of superhot fire exploding outward. Every aspect of the universe we inhabit today, from quarks to quasars, was implicit in the Big Bang beginning.

It is a wild, beautiful story — creation as a singular, blazing fire — and Teilhard had seemed to anticipate it. It was the Sixties, after all, a time of revolution and renewal, and suddenly science and faith were on the same track.

Or so we believed.

From a perspective of forty years on it is clear that what we found in Teilhard popular writing has very little to do with science. There is nothing that can be construed as a useful framework for research. Re-reading Teilhard’s books today, I blush at the jargon I once took so seriously.

In his famous review of Teilhard’s The Phenomenon of Man, the distinguished biologist Sir Peter Medawar found nothing to like and much to detest; the book, he said, “is written in an all but totally unintelligible style, and this is construed as prima-facie evidence of profundity.” Ouch! But Teilhard’s prose does now seem that of a man who is trying to have his cake and eat it too, the same old theology of sin and salvation tricked up as pseudoscience. Even Sir Julian Huxley, who wrote the introduction to the English edition of The Phenomenon of Man, professed himself unable to follow Teilhard “all the way in his gallant attempt to reconcile the supernatural elements in Christianity with the facts and implications of evolution.”

But let me not be so ungenerous — to Teilhard or to my younger self.

Behind Teilhard’s breathless Godspeak, one senses a person caught between rebellion and obedience, struggling against the authority of his Church, yet honoring tradition. In this he is not so far from those of us today who seek some sort of reconciliation between science and spirit.

Teilhard was a scientist, yes, and a good one, but he was first and foremost a poet and mystic. His great gift as a man of faith was to embrace unhesitatingly the scientific story of creation. He began with the evolving fire and drew it down into the heart of his world.