Originally published 18 January 1993

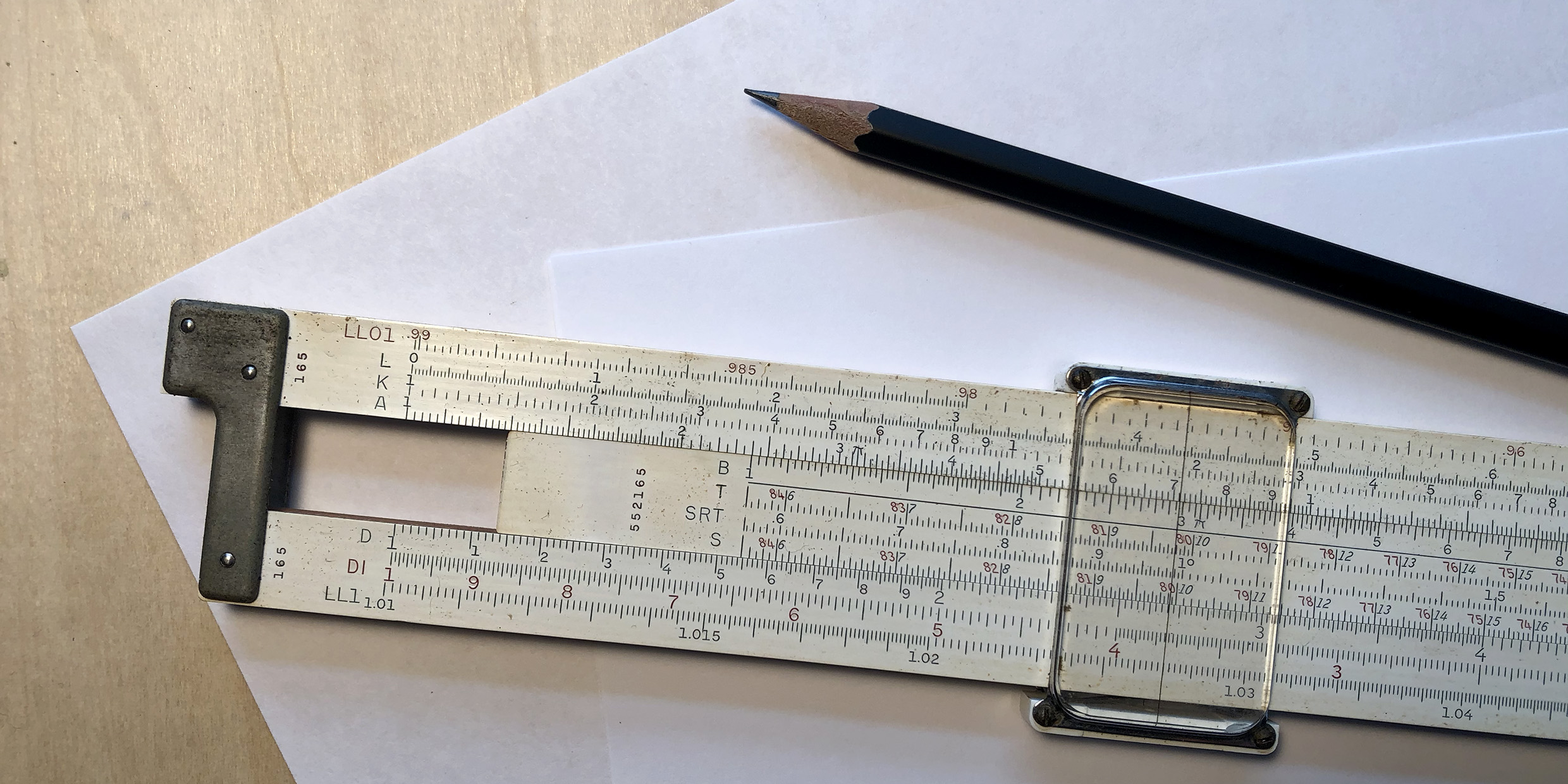

My father’s slide rule.

I found it at the back of a bureau drawer during a recent visit to my mother’s home in Tennessee.

An excellent Keuffel & Esser log-log-duplex-decitrig slide rule from the 1940s, with white plastic scales bonded to teak and a glass hairline indicator, neatly cozied in a stiff leather case. Twenty-one separate scales.

My father was a man who took his slipstick seriously.

He used it all day long, every day. In his work. In his play. While tinkering in his basement workshop or preparing a speech for the local chapter of the American Association of Mechanical Engineers.

He lived in a world of three significant digits. That was the accuracy with which he read his measuring instruments, and that was the accuracy of the calculations he performed on his slide rule. It was enough for a tidy, self-contained life of service to his profession and his community.

Never far away from the slide rule was a pile of Keuffel & Esser graph paper, heavy stock paper with green lines and light stock paper with orange lines, in an assortment of scales. Linear, semilog, log-log. A paper for every purpose.

He plotted everything. The many aspects of his work. The family finances. The stock market (although he owned no stock). The weather. Only when he saw data displayed on a graph did he feel he understood it.

Even on his deathbed he was slipping his slipstick and plotting the cycles of medication and pain.

Slide rules and graph paper have gone the way of the dodo and passenger pigeon, replaced by pocket calculators and computer monitors. Thus, the strange emotions I felt when I found the slide rule at the back of the drawer, like an archeologist unearthing a flint blade or clay lamp.

The first emotion, I suppose, was nostalgia. For my father. For a world where thought and things went hand in hand. With a slide rule, the structure of thinking was visible and tactile. You could see and feel the numbers add, multiply, divide. With a super-sharp pencil tracing a line on beautiful K&E graph paper you physically participated in the patterns that gave order to the world — and to a life.

Today, I punch numbers into a calculator or a computer. The processing takes place invisibly in a microchip forever sealed from human inspection. Graphs are generated by software. They appear on a video screen and pop out of a laser printer. The wonderful, sensual feel of thinking with wood, steel, paper, graphite, and glass has been sacrificed to speed, convenience, and a degree of precision unimaginably greater than the tolerances of daily life.

But more is going on here than an advance in technology. The change from slide rules to calculators is different, say, than the change from oil lamps to electric bulbs, or from horses and buggies to automobiles. The passing of the slide rule prefigures a change in the way we understand the world.

It is a change from nuts-and-bolts materialism to mathematical formalism, from a world imagined as hardware to a world imagined as software. The dance of digits inside a computer’s silicon chip seems destined to become the 21st century’s metaphor for reality.

It is the rare scientist these days who does not use a computer as an indispensable accessory to thought. Biologists explore the dynamics of evolution with artificial life forms in computers. Chemists perform experiments with digital molecules. Cosmologists watch galaxies collide on computer screens.

Even astronomers have turned away from their telescopes; instead, electronic eyes peer though the scopes and display digital images on video screens. The images are teased and stroked by computers, and made to reveal their digital secrets.

The microchip, in its indispensability, its speed, its precision, its versatility, is irresistibly imposing itself upon the way we think. The material reality of Galileo and Newton is yielding to bits and bytes. Instead of imagining the essence of things in the guise of wood, steel, paper, graphite, and glass, scientists are thinking of digital essences — a universe of ones and zeros evolving according to a cosmic program.

None of this is to be lamented. It is a step forward in our continuing quest to understand the world. We are the computer generation; it is inevitable that we would develop a taste for a digital universe.

My father’s death coincided with the advent of cheap, powerful calculators and personal computers. After his death, his piles of K&E graph paper went out with the trash. His slide rule somehow made its way to the back of a bureau drawer. Finding it there, I was indeed an archeologist unearthing a cultural artifact from a vanished era.