Originally published 4 January 1999

Let’s get a jump on end-of-year hoopla and ask now: Who is the “Person of the Millennium”?

Who is the person who for better or worse most profoundly influenced the course of history during the past 1,000 years, and might that person be found in the ranks of scientists and technologists?

Here are some possible candidates, admittedly a Eurocentric list:

Christopher Columbus. With a bold voyage across an apparently boundless sea he turned the world upside down, shattering ancient civilizations of the Americas, supplanting them with European colonies far from the reach of monarchs. He caused massive treasure to flow into Europe’s coffers, fueling the nascent Renaissance with cash. His discovery of a “New World” set off an imperial scramble that would ultimately spread European ideas and values around the planet.

Martin Luther. Posting a set of 95 theses against indulgences on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany, he changed the way humans relate to their God. No longer would the Church hold exclusive keys to the kingdom of heaven; no longer would prayers ascend to God only through channels controlled by the Pope. In Luther’s theology we find the germ of an enabling freedom, in which every individual stands equally before the divinity, Bible in hand.

William Shakespeare. In a recent book, the scholar Harold Bloom maintains that Shakespeare invented the modern idea of what it means to be human, by creating characters who are introspective, who have personalities, and who shape, not simply react to, the forces of history. “The ultimate use of Shakespeare,” Bloom asserts, “is to let him teach you to think too well, to whatever truth you can sustain without perishing.” And of course no one, with the possible exception of the authors of the King James Bible, had a more powerful influence on the English language.

Galileo Galilei. The truth about the world is to be found in the Book of Nature, said the great Florentine physicist. Neither revelation, nor tradition, nor the authority of modern churchmen or ancient philosophers supersedes the evidence of the senses. He was the first truly modern scientist, in every sense of the word. The experimental method that he almost singlehandedly invented is the source of our health, wealth, and technology.

Thomas Jefferson. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” These words have come to define the only acceptable government, deriving its powers from the consent of the governed. Jefferson stands for a galaxy of exceptional men — Washington, Madison, Hamilton, Adams, Jay, and others — who miraculously appeared at our aborning nation’s hour of need and changed forever the flow of world history.

Charles Darwin. Of all thinkers of the millennium, none has so fundamentally altered the way we understand our place in the cosmos. Darwin’s achievement was not just to propose the unity of life by common descent, not just to offer a mechanism — natural selection — by which nature directs its creative impulse, but to so buttress his theory with evidence that it swept all before it. After Darwin, it would never again be possible to imagine humankind as anything other than embedded in a tangled web of time, matter, energy, life.

Together, these individuals can be said to have contributed to the great millennial theme of growing individual freedom — freedom from tyrannies of body, mind and spirit. However, none of these men could have achieved his influence on history had it not been for the innovation of one other mostly unacknowledged person.

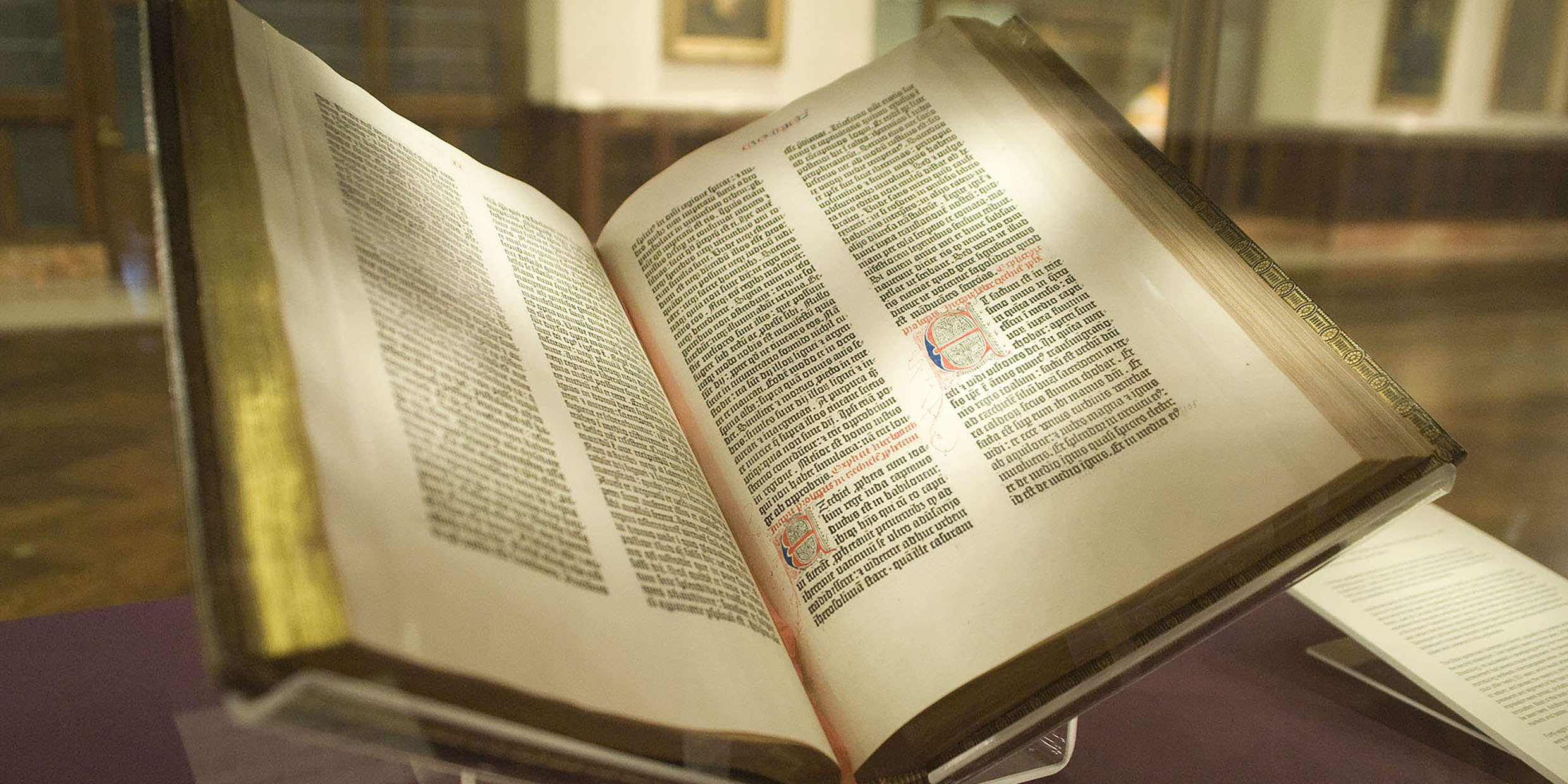

Johannes Gutenberg. Of all these “persons of the millennium,” we know least about Gutenberg. Details of his life and work are drawn mostly from records of the lawsuits that plagued him throughout his career. The man we see behind the epic invention — printing on a press with reusable diecast metal type — was the son of a patrician of Mainz, Germany, born in the last decade of the 14th century. In 1455, he completed the famous Forty-two Line Bible that was his masterpiece, the first printed book in Europe, and the first in the world to be disseminated widely.

It would be wonderful to know more of the creative life of this obscure man who brought together so many ingenious innovations into one seamless new technology. He was clearly driven by a vision of mechanizing the production of beautiful medieval illuminated manuscripts, step by step, from words in black ink on white paper to polychrome decorations. What he achieved was no less than a revolution in human communication, releasing the mass of people from the demanding necessity of orally preserving a record of history.

Once the accumulated knowledge and wisdom of the past was permanently fixed in readily available books, the energies of humankind were released for the creation of more knowledge. Printing changed “the appearance and state of the whole world,” said Francis Bacon. Certainly, it is hard to imagine Columbus, Luther, Shakespeare, and Galileo except in the context of printed maps and books. Without books, no Enlightenment — no Jefferson, no Darwin.

If there is a single persuasive symbol of the millennium’s drive towards the affirmation of individual freedom, it is the printed page you are holding in your hand.