Originally published 7 October 1991

Dr. Seuss in the science pages?

You bet.

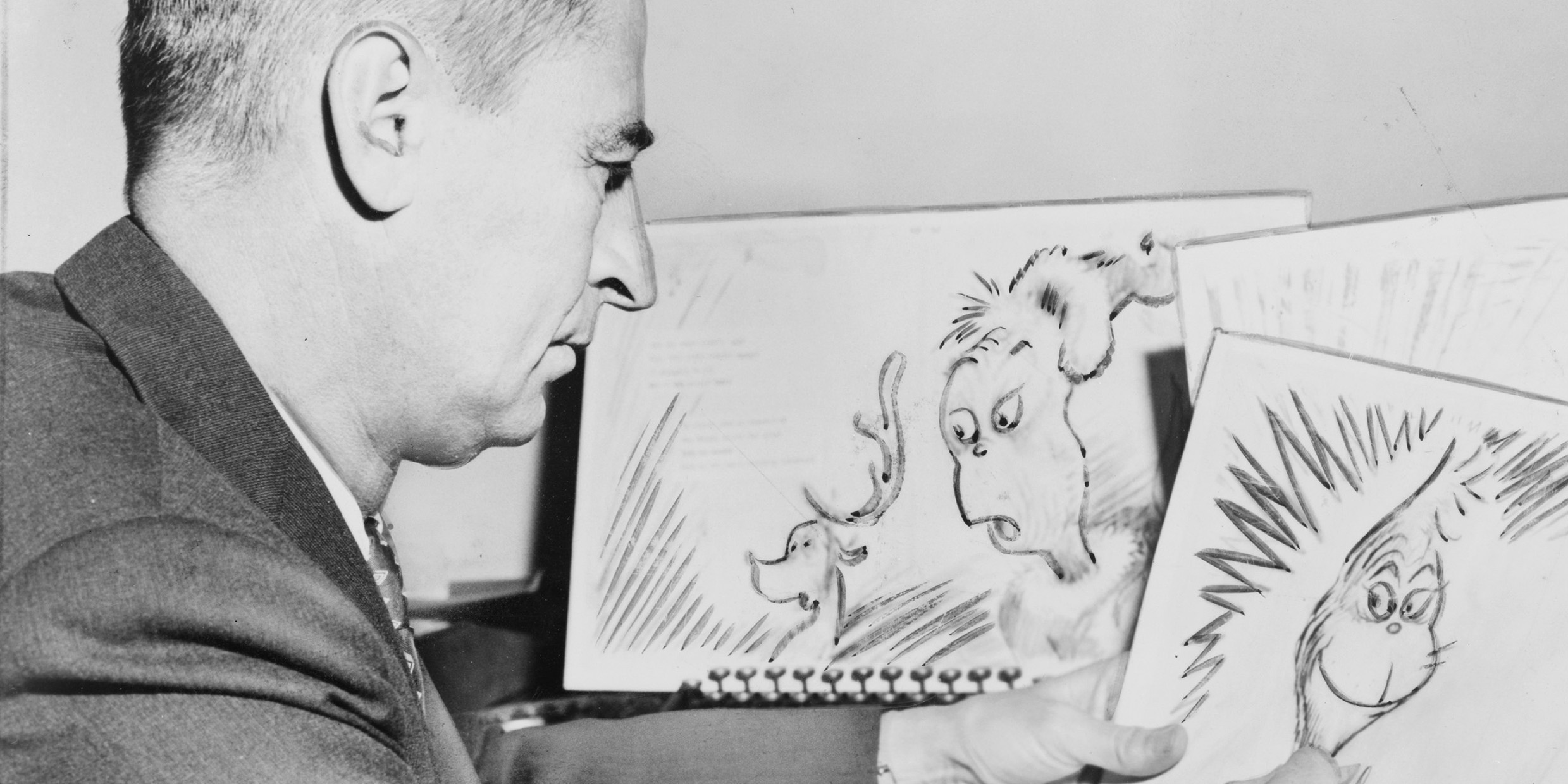

Dr. Seuss, a.k.a. Theodor Geisel, who died [in 1991] at age 87, was a botanist and zoologist of the first rank. Never mind that the flora and fauna he described were imaginary. Any kid headed for a career in science could do no better than start with the plants and animals that populate the books of Dr. Seuss, the master of madcap biology.

They are great stretching exercises for the imagination.

A few years ago, when thrips were in the news for defoliating sugar maples in New England, I noted in a column that some species of the insects lay eggs, some give birth to live young, and at least one species has it both ways. I suggested that not even the wildest product of Dr. Seuss’ imagination — the Moth-Watching Sneth, a bird that’s so big it scares people to death, or the Grickily Gractus that lays eggs on a cactus — is stranger than creatures that actually exist.

Not long after, a reader sent me a photograph of a certain tropical bird that does indeed lay eggs on a cactus.

And what about the Moth-Watching Sneth? The extinct elephant bird of Madagascar stood 10 feet tall and weighed a thousand pounds. In its heyday (not so long ago) the elephant bird, or aepyornis, probably scared many a Madagascaran half to death. For all we know, it watched moths too.

Nature the equal to Seuss

Pick any Seussian invention and nature will equal it. In Dr. Seuss’ McElligot’s Pool there’s a fish with a pinwheel tail, and a fish with fins like a sail. There are young fish (high-jumping friskers), and old fish (with long flowing whiskers). But the strangest fish in McElligot’s Pool is the fish with a kangaroo pouch. Can there possibly be a real fish…? Wait! Not a fish, but in South America there is an animal called the Yapok (really!) that takes its young for a swim in a pouch, the only water-going marsupial. The Yapok is an excellent swimmer and diver (no slouch), with paddle-web feet and a waterproof pouch.

At this point the boundary between the real world and the Seuss world begins to blur. Consider the life cycle of the brain worm, Dicrocoelium dendriticum.

Adult brain worms are skinny and flat like noodles. They live in the livers of sheep. Oodles and oodles of their eggs travel down the sheep’s intestines and are excreted into the grass. There they lie, quiescent, until a dung-eating snail happens to pass. Gobbled, the eggs awaken, in the snail’s gut, and turn themselves into roundish things that drill their way through the gut to lodge themselves in the snail’s digestive gland. Thus ensconced, they change again, into a stringy sort of thing called a mother sporocyte. The MS (as I’ll call her), clones herself into a zillion copies, or daughter sporocytes, filling the snail’s digestive gland to overcrowding. The jam-packed DS’s (as I’ll call ’em) change again, into spermlike creatures, called cercaria, that migrate to the snail’s respiratory chamber. Snuffling and sniffling, the clogged-up snail coats the cercaria with mucus and sneezes the slime ball into the grass. The slime keeps the cercaria moist and alive, but — wonder of wonders — the slime ball looks exactly like a snail’s egg. Along comes a wood ant with a taste for snail’s eggs that lugs the slime ball back to the nest for dinner. Devoured, the cercaria change into metacercaria, most of which take up housekeeping in the ant’s abdomen. A few metacercaria travel to the ant’s brain, where they twiddle the controls and cause the ant to go a particular kind of crazy. The ant crawls up to the top of a grass stem and sits there in a catatonic state until — yep, you saw it coming — a sheep nibbles the grass. The sheep’s pancreatic juices cause the metacercaria to hatch into young brain worms that make their way to the sheep’s liver and…

Every step of this quirky journey, including the sheep, the snail and the ant, is necessary if the brain worm is going to reproduce. The Creator who invented the brain worm out-seussed Seuss.

Millions of species

One fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish: They are all here, somewhere. Ten million (or more) zany species. A fish with a long curly nose. A fish like a rooster that crows. A fish with a checkerboard belly. A fish made of strawberry jelly. Am I making them up? Is it Seuss or reality?

A thousand-pound bird (if you meet one, don’t mock it); a deep- diving Yapok with waterproof pocket; a switch-hitting thrips that is bi-reproductive; a brain worm whose hosts are just-out-of-lucktive. All there, as real as real. Like the famous physicist Michael Faraday said, “Nothing is too wonderful to be true.”

So farewell to you, wonderful Dr. Seuss. And thanks for teaching us all a great lesson about biodiversity: If we wait long enough, if we’re patient and cool, who knows what we’ll catch in McElligot’s Pool.