Originally published 27 April 1987

It has been 30 years since British scientist and novelist C. P. Snow created a stir among educators with his idea of the “two cultures.” According to Snow, “scientific culture” and “literary culture” have become separated by a gulf of mutual incomprehension, often marked by hostility and dislike. Scientists have nothing to say to those who practice or study the arts — and vice versa. Each culture has its own language and agenda. Each is impoverished by ignorance of the other.

Stung by Snow’s challenge, the colleges and universities tried to patch up the split. Curriculums were changed to expose students of the humanities to the history and philosophy of the sciences, and to make young scientists more sensitive to the arts. Some of these changes were washed away in the educational upheavals of the late 1960s; others continue to limp along in the present curriculum.

And now comes Allan Bloom, a philosopher of political thought at the University of Chicago, to tell us that the problem is as great as ever. Bloom’s current best-seller, The Closing of the American Mind, is a querulous and provocative attack on contemporary higher education. Bloom finds little to admire in the colleges and universities today, and among many failings he includes the mutual isolation of the sciences and the arts.

Not two but three cultures

Bloom concurs with Snow’s diagnosis, and takes it a step further: The intellectual life as practiced and taught in our institutions of higher learning has been “decomposed” into not two, but three mutually exclusive camps — the natural sciences, the social sciences, and the humanities.

Of these three, Bloom sees the natural scientists as aloof and alone, utterly confident of the value of their work, and sublimely indifferent to the rest of the university (except when political activity is required to insure the integrity of their departments or financial support). According to Bloom, natural scientists dismiss the social sciences as “imitations” of real science, and consider the humanities — respectfully, of course — as a kind of “day-care center” where those who ask childlike questions — Is there a God? Is there freedom? What is a good society? — are amused while the adults — scientists — go about the grownup work of discovering what nature is.

The natural scientists, says Bloom, are the elitists of the university, secure in their belief that the only real knowledge is scientific knowledge. It is inconceivable, he asserts, “that a physicist qua physicist could learn anything important, or anything at all, from a professor of comparative literature or of sociology.” And Bloom’s gloomy assertion is probably true. The academy is fragmented, and all the king’s horses and all the king’s men will have a hard time putting it back together.

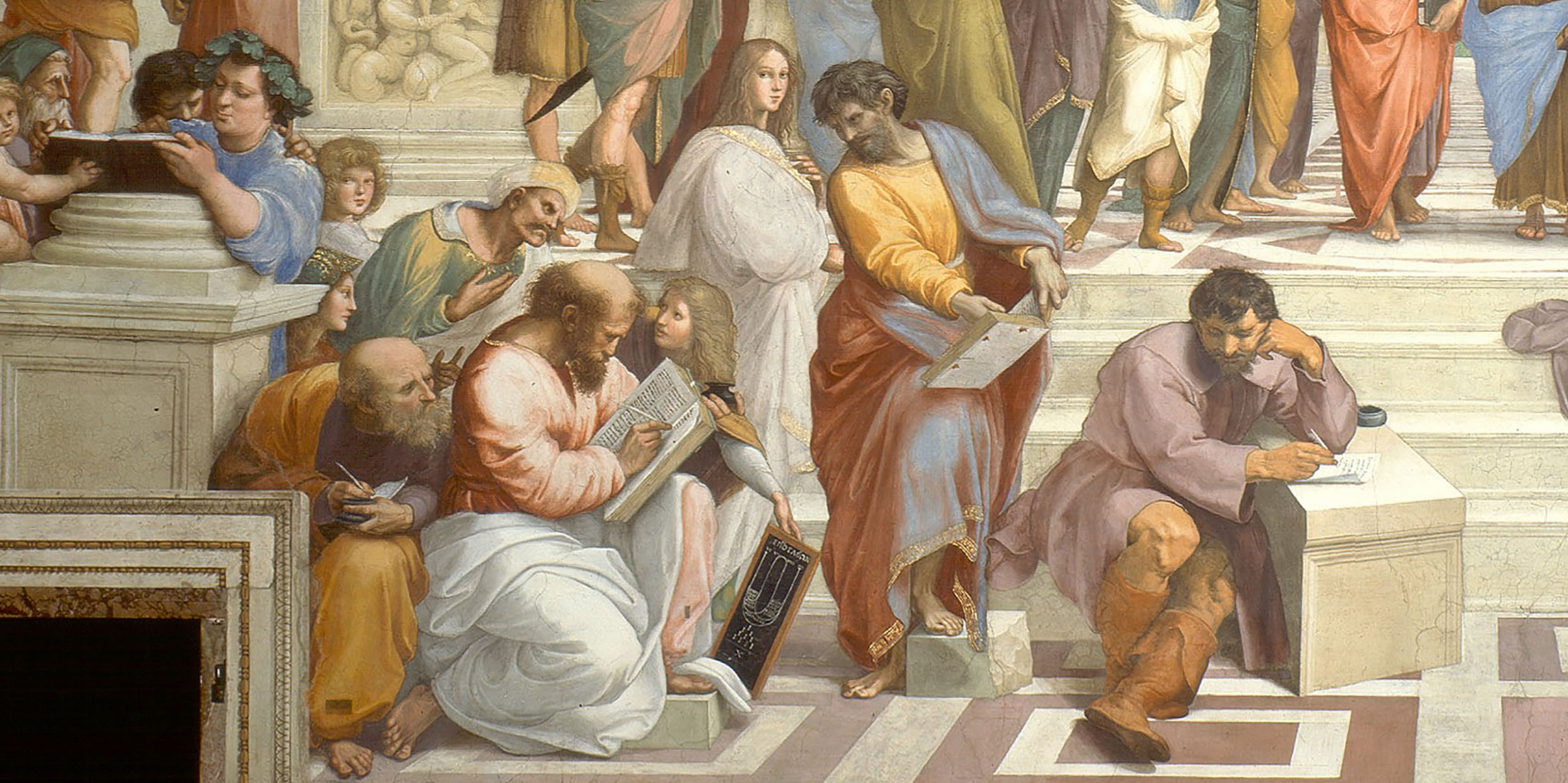

To remedy this unfortunate state of affairs Bloom offers nothing more than the doddering suggestion that we should all read the Great Books and share (at least) that common ground. It is easy to agree with Bloom that all graduates of the university — natural scientists, social scientists, and students of the humanities — should know Thucydides, Shakespeare, Darwin, and so forth. It is less certain that a shared experience of the Great Books will have much effect on the way we go about our intellectual business.

For one thing, science no longer produces Great Books; science has become a very different sort of enterprise from what was practiced by Newton and Galileo. Reading the Great Books will not help students of the arts appreciate what science is today, nor will reading Sophocles and Marx help scientists win grants for their research. The gulf between the cultures will endure.

A cultural loss

These melancholy thoughts on the two — or three — cultures were prompted by news of the death of Primo Levi, the Italian chemist, writer, Auschwitz survivor, and commentator on the human condition, who died two weeks ago [in April 1987] at the age of 67. Levi acquired international recognition a few years ago with the publication of The Periodic Table, a book that wove seamlessly together chemistry, human relationships, and the soarings and plungings of the heart. It was a book that impressed almost every reader as wise, humorous, literate, and free of intellectual posturing.

For Levi, there were no gulfs between cultures. He was a chemist, a humanitarian, and a poet, and no one of these activities was separate from the other. Levi knew the Great Books; he was also a chemist who knew intimately the secret lives of oxygen, hydrogen, nickel, and lead.

Primo Levi showed us the possibility of a way of living that would make the laments of Snow and Bloom simply irrelevant — if only we could figure out how to teach it.