Originally published 24 July 2005

In the fall of 2003 I walked the prime meridian, the line of zero longitude, across southeastern England, visiting many sites important to the history of science. An account of that walk is forthcoming, in a book titled Walking Zero: Discovering Cosmic Space and Time Along the Prime Meridian, to be published by Walker & Co. in 2006.

One stop along the way was the former home of Dr. Gideon Algeron Mantell, Victorian gentleman geologist and discoverer of the first dinosaur fossils. Mantell’s house in the town of Lewes in Sussex stands only feet away from the prime meridian.

In October 1821, a twenty-four year-old aspiring geologist named Charles Lyell knocked on Mantell’s door. Lyell was drawn to Lewes by Mantell’s established reputation as a fossilist. The two men sat talking until the early morning hours, and a lasting friendship was established. They became firm allies in the subsequent battle to wrest geological time from the biblical literalists. Lyell was to become the premier geologist of his time, the author of Principles of Geology.

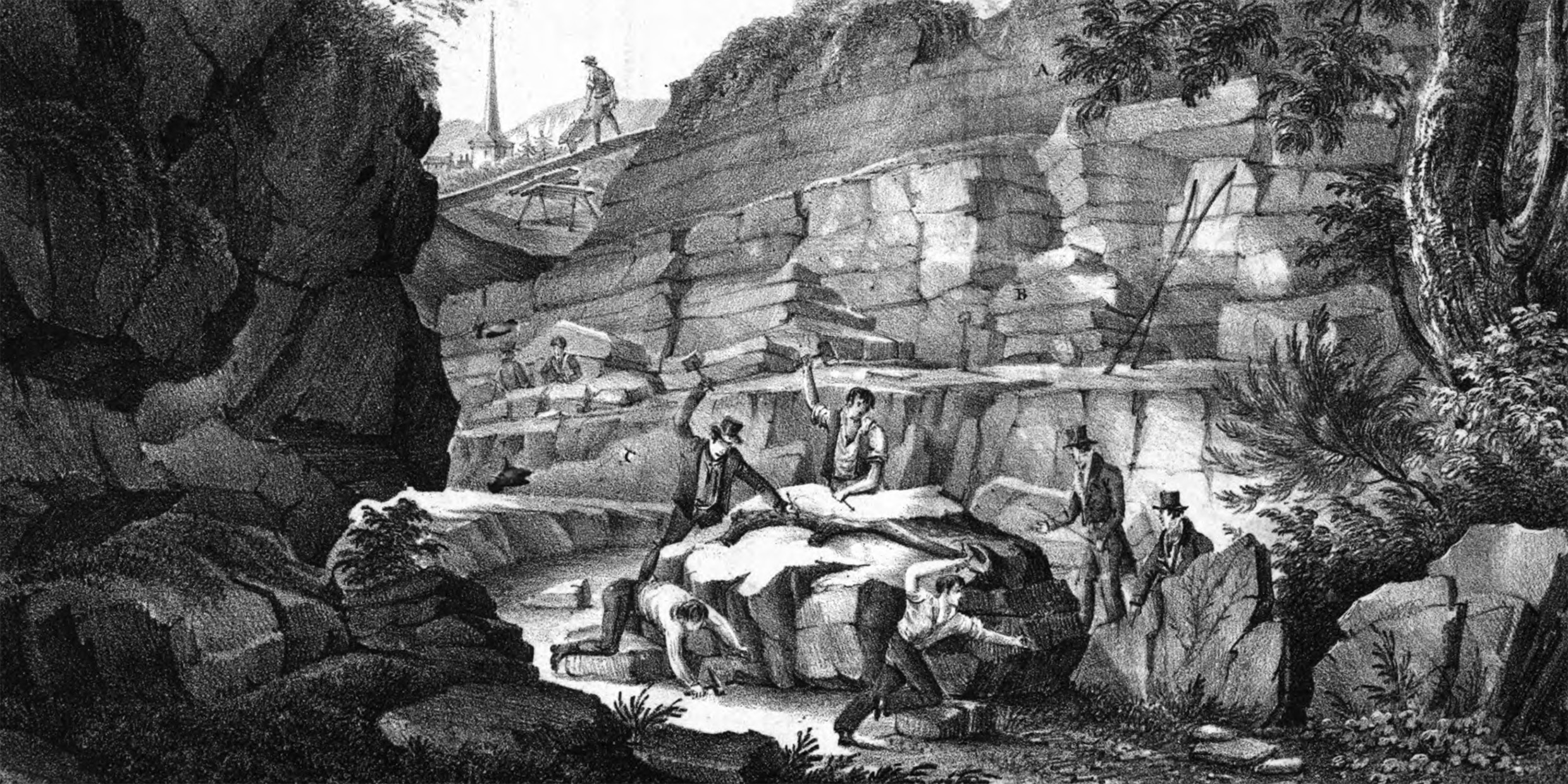

A print used as the frontispiece of Mantell’s Illustrations of the Geology of Sussex (1827) depicts a visit made by Mantell, Lyell, and William Buckland, the first professor of geology at Oxford University and a biblical literalist, to the quarry at Cuckfield, a village 10 miles northwest of Lewes which had yielded up Mantell’s dinosaur bones.

It is a rainy afternoon in March, 1825. The three geologists are in top hats and gentlemanly garb. They are accompanied by half-a-dozen less formally attired quarry workmen. Mantell is presumably the person at right, standing behind a vertical slab of sandstone etched with a fossil fern. Lyell or Buckland wields a hammer to release a reptilian bone from the rock. In the background is the spire of Cuckfield Church (the quarry has since been filled in and a cricket field stands in its place).

The picture lends itself to metaphorical interpretation. Whatever the theological differences between Lyell and Mantell, on the one hand, and Buckland, on the other, it is clear that the story of the past will ultimately depend upon the evidence of the fossiliferous strata and not upon the authority and tradition represented by the distant church spire. I particularly like the conjunction at the right of fossil ferns and living plants, reflecting each other mirrorlike across eons of geologic time. The present is the key to the past, believed Mantell and Lyell, following the Scots geologist James Hutton; if we want to understand the history of the Earth and its denizens, let us look to natural forces at work on the globe today and apply them to the past.

Mantell’s journal entry for May 21, 1831, recounts the expedition he made with Lyell to another nearby quarry at Horsham, where the two fossilists happily examined slabs of ancient sandstone covered with ripple marks. Mantell described these sandstone surfaces in a note to the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. No one who has observed the action of waves on a living beach can doubt that the identical undulations in ancient sandstones were made by the same agency, asserts Mantell. Then he pens a line that is as relevant today as in his own time: “Obvious as the cause of this curious appearance seems to be, yet it has been a subject of dispute among men of science, the mind being but too apt to seek for a mysterious agent, to explain effects which have been, and are still being, produced by some simple operation of nature.”

What that “mysterious agent” might be has varied from time to time and place to place, but almost invariably is has taken the form of a humanlike intelligence, or animal creator with human qualities. The psychologist Jean Piaget has shown us that young children invariably evoke artificialist explanations of natural phenomena, so that even Sun, Moon, wind, and clouds become the products of a conscious agency who has acted with particular reference to the child. Likewise, anthropologists see artificialist explanations at work within so-called “primitive” cultures around the globe. Middle-eastern creation myths, such as that recounted in Genesis, are among common examples of the artificialist tradition. The tendency to understand natural phenomena in a way that evokes a humanlike agency is very strong indeed. The present brouhaha in the United States over Intelligent Design is just the latest of artificialist explanations.

When Hutton, Lyell, and Mantell suggested that the present is the key to the past, they were proposing a kind of explanation that was destined to transform the world in ways they could hardly have imagined. It might even be said that they turned the world upside down; previous explanatory systems assumed that the past — enshrined in authority, scriptures or tradition — is key to the present. Rooting around in the quarries in Sussex, Mantell, and Lyell turned explanation topsy-turvy.