Originally published 20 October 1986

In Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Miranda grows to the age of sixteen on an ocean isle with no human companions other than her father Prospero and the monster Caliban. When storm and shipwreck bring others to the island she is suddenly awakened to the variety and beauty of mankind. “O brave new world,” she exclaims, dazzled,“that has such people in’t!”

Early this year [1986], after a voyage of 8 1/2 years, the spacecraft Voyager 2 passed within 18,700 miles of a little world named Miranda, one of the moons of Uranus. Miranda is about as big as Colorado. It lies almost three billion miles from Earth.

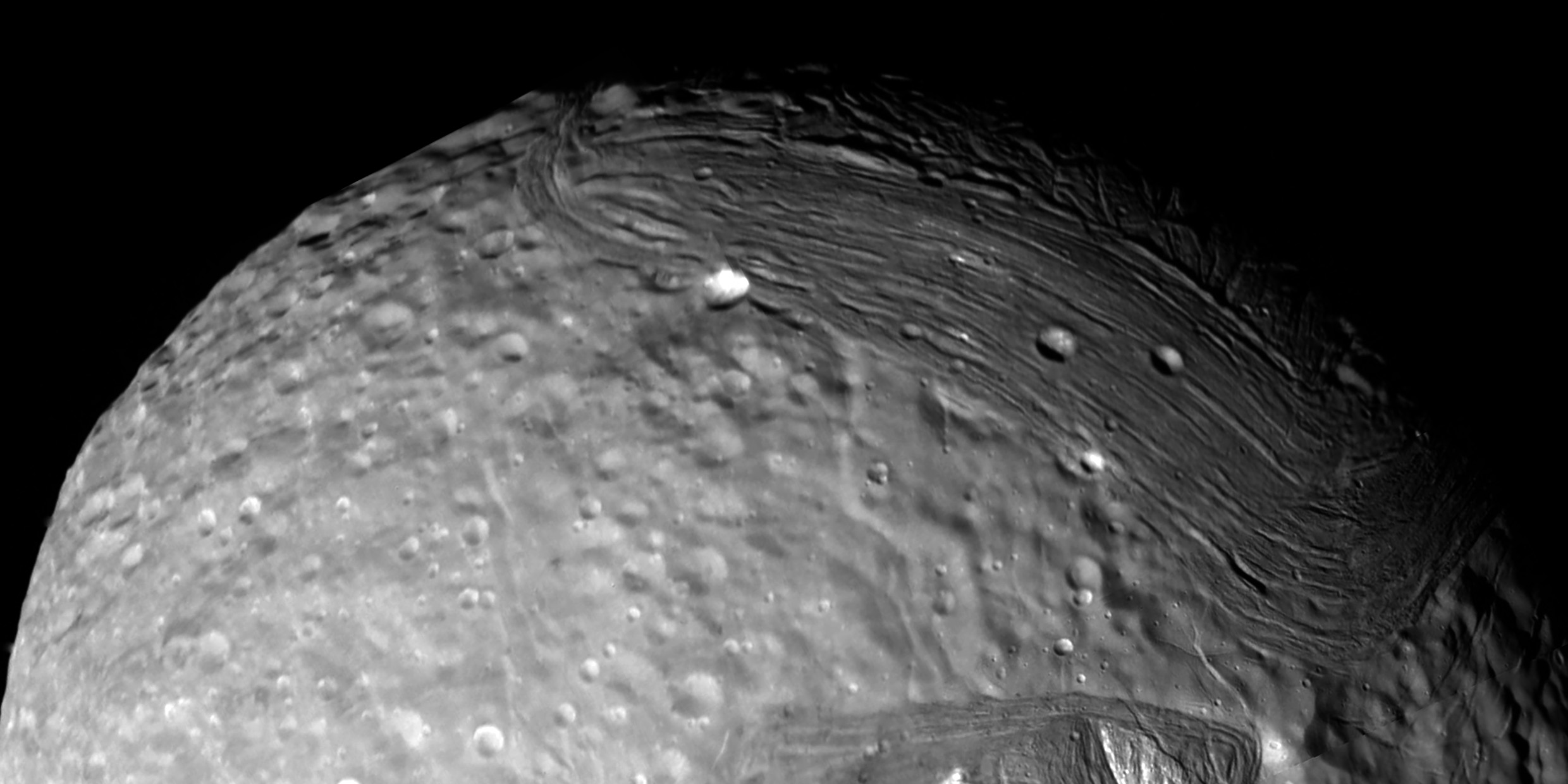

As Voyager sailed past Miranda, it turned gracefully to keep its camera aimed precisely at the little moon. The image beamed back to Earth was of stunning clarity. It showed features no larger than the Boston Common. Miranda’s icy surface was pocked with craters and lidded with mysterious looping folds of crinkled crust. From the deeps of space and the abysm of time Miranda seemed to wink. And we, seeing the image, could only blink with wonder at a universe that has such objects in it.

The voyage of Voyager 2 is one of the great success stories of space exploration. The craft has outperformed the most optimistic expectations of the engineers and scientists who launched it in 1977. It followed its companion, Voyager 1, to Jupiter and Saturn, and then sailed on to Uranus. With luck, it will still be alive and feisty when it reaches Neptune two years hence. The images it has collected of the outer worlds of the solar system have changed forever the way we think about the universe.

Encounter with a monster

First came the encounter with giant Jupiter, the monster planet, eddied with storms of yellow, red, and orange like a can of freshly pigmented paint stirred with a stick. And against that improbable backdrop of psychedelic drapery — the moons. Sulfurous Io, plumed with volcanic activity, bubbling with nether-worldly fire. Reticulated Europa, crevassed like arctic sea ice, cobwebbed with thin ridges and strangely devoid of craters. Ganymede, the frosted giant, its surface trenched and blasted like the battlefield at Verdun. And, Callisto, ice crusted, densely cratered; a huge many-circled impact feature on Callisto gives that moon the appearance of a struck brass gong.

Then on to ringed Saturn, which the Voyagers reached in 1980 and 1981. Saturn’s rings are so improbable that they were observed telescopically for fifty years before anyone dared to guess what they were. Voyagers’ cameras resolved the rings into hundreds of concentric circles of light reflected from orbiting particles. No saint painted by Giotto ever wore a more splendid halo than huge Saturn.

Each of Saturn’s moons held its own surprise. Mimas, with its perfect dimpled moon-sized crater; Mimas looks so much like Darth Vader’s Death Star spaceship that one would be willing to credit George Lucas with a kind of spooky prescience. Bright-dark Iapetus, its leading hemisphere only one-tenth as bright as the icy trailing backside. Enigmatic Enceladus, almost a twin to bigger Ganymede. Tumbling, chunky Hyperion. Tethys, Rhea, and Dione, like wheels of green (and pink, and yellow) cheese. And Titan, the only one of all these worlds large enough to be shrouded in gas.

Voyager 2 used Saturn like a gravitational slingshot to toss itself outward across the next great gulf of space toward Uranus. Meanwhile, the engineers tinkered and toyed with the spacecraft by remote control, trying to fix the mechanical and electronic troubles that had plagued the craft through its long journey. Reaching Uranus had been an unofficial goal when the craft was launched, and only the most confident members of the Voyager team dared to dream that the little vehicle would successfully traverse such enormous distances and still stay tuned to Earth.

An engineering feat

There is an excellent article about these heroic feats of ground-based engineering by J. Kelly Beatty in the October [1986] issue of Sky & Telescope magazine. As Beatty makes clear, the Voyager 2 that reached Uranus early this year was a better craft than the one launched in 1977. And the image it sent back of the little moon Miranda was the most beautifully detailed of any in the craft’s long flight.

Voyager 2 collected other Shakespearean images as it passed by Uranus. The rifted moon Titania, rising from enchanted sleep. “Night-ruled” Oberon. Active icy Ariel, a “fine apparition.” Dark, mysterious Umbriel, sharer of these moonlight revels. In addition, Voyager 2 discovered ten tiny new moons in the Uranus system, including one unofficially nicknamed Puck. And of course, there was Uranus itself, the shepherd of this magnificent flock, with delicate, head-on rings resplendent in the light of a very distant sun.

At Uranus, Voyager 2 got another gravitational kick that sent it flying on toward Neptune. At Neptune’s distance from the sun, the sun is a thousand times less bright than on Earth. In 1989, if all goes well, Voyager 2 will sip that attenuated light, reflected from Neptunian worlds, to send back images still more beautiful and various than any yet seen. Plucky, lucky Voyager 2 is the little spacecraft that could.

In one of the great success stories of human engineering, as of 2019, Voyager 2 is still in contact with Earth and exploring the universe, forty-two years after launch. ‑Ed.