Originally published 3 March 1997

I had come a long way to see him, across half of France, to the Castle of Cloux, near Amboise, in the valley of the Loire. He had been living there since 1516, at the invitation of Francis I, king of France.

The king likes to surround himself with luminaries — artists, poets, philosophers, talented people of all sorts. Leonardo’s reputation, of course, was known throughout Europe. It was inevitable that the king would draw him to France.

When I met him, I asked why he had left Italy. He answered with surprising candor: “I was living in Rome. Michelangelo and Raphael were there also. How was I to compete with those younger men? Those two! And then my patron, Giuliano de’ Medici, died. It was the passing of an era, a time of indefinite promise, possibility, experimentation…”

His thoughts drifted off.

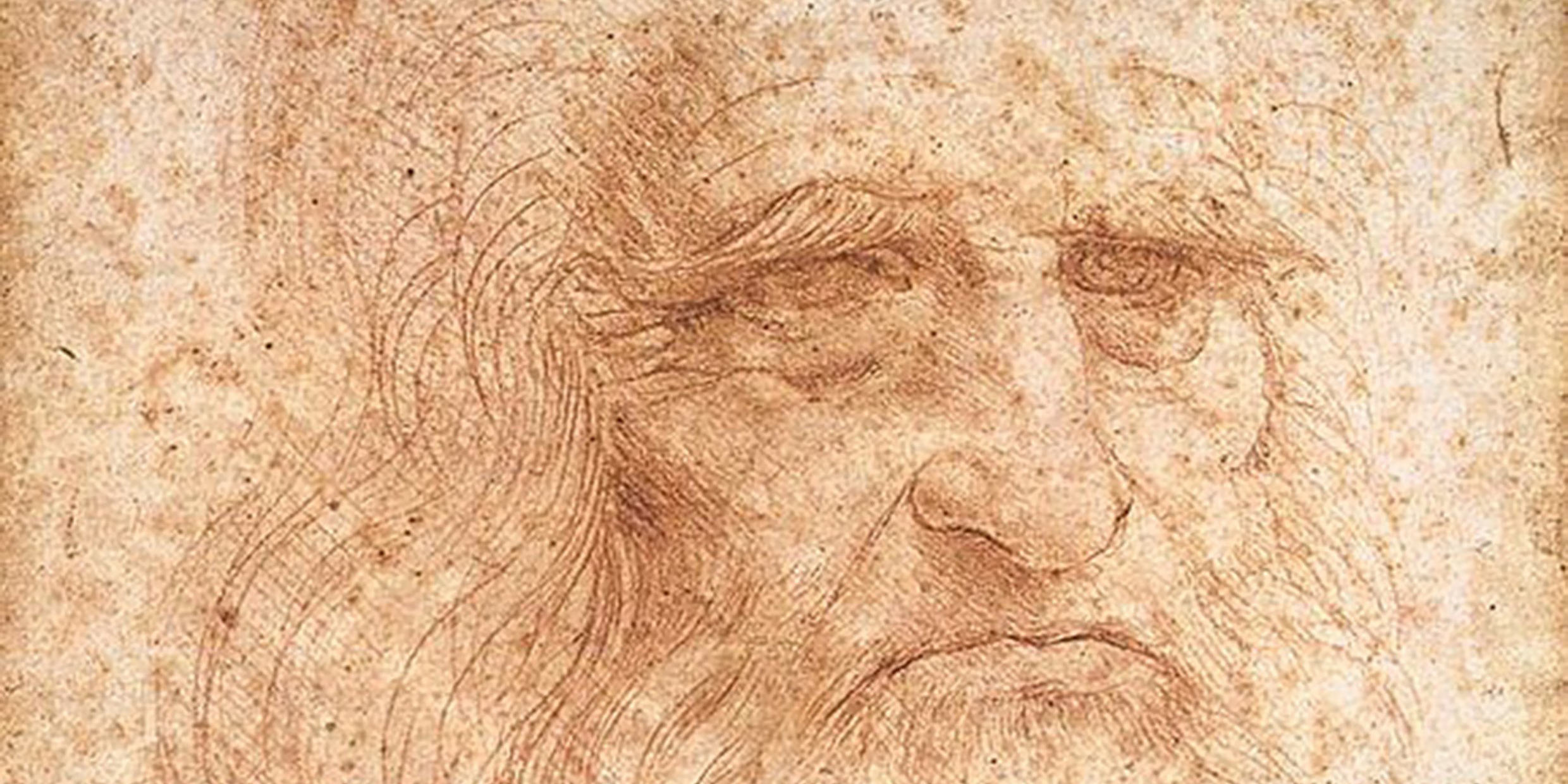

He was 66 years old. Within a year he would be gone, although I would not have guessed it then. His face showed age but not infirmity. Long white hair, unkempt, fell about his shoulders. White beard. Thick, down-swept brows shaded his eyes like awnings. A strong nose. And of course the mouth, serious yet generous, not unlike the mouth of the Christ he had painted on the wall of the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

He received me cordially, invited me to sit with him near the fire. His life at Cloux was comfortable; he lacked for no luxury. He enjoyed the company of artists and musicians, the attention of royalty. I asked him if he was content.

He was silent for a long time. “Content is not a word I would use,” he said. The corner of his mouth turned up just a little. “So much. So much unfinished.”

I asked what he meant.

“I have been unlucky,” he said. “So much of my work destroyed or left incomplete. So many dreams unfulfilled. I fear that when I am gone I will soon be forgotten.”

He fingered the rich cloth of his garment. “The clay model of my equestrian statue of Ludovico Sforza — irreparably damaged by soldiers. My fresco of the Battle of Anghiari—decayed upon the wall before it was finished, the price, I suppose, of experimentation. The Adoration of the Magi, St. Jerome—mere sketches of the works they might have been.”

“Why?” I boldly asked. “Why so little to show for so long and rich a life?” I might have guessed his answer.

He shook his head and smiled. “One thing led to the next. I would start to paint a human hand — the hand of Madonna, say — and the flesh of the fingers would draw me to consideration of the bones of the fingers, and how they are articulated, and this would require dissection of a cadaver. The play of light on the flesh of the fingers would lead me to the study of meteorology, sun, rain. Storm and river. Mountains. How do the crags resist the rain? Why seashells upon the peaks? Each rock, each plant…”

He paused. Then quietly: “Look at the faces of the men and women in the street, when evening falls and the weather is bad. What grace and sweetness there is in them. How was I to translate what I could see with my eyes into the medium of paint on panel? Painting the flesh is easy, but how does one paint the soul’s intention? One thing led to the next, you see. It is all connected.”

I asked about his many mechanical inventions.

“There is nothing to invent that is not already present in nature. The veins of a leaf, the bones that bear the membrane in the wing of a bird, threads of ore within the earth. These motifs recur. There are structural principles that even the Grand Designer must employ. The inventor’s task is to discover these principles, exploit them…”

I said: “I have noticed these similarities in your work — the curls in the hair of your subjects, convolutions of air and water, explosions…”

“Yes, yes. This is what made it so difficult, so difficult to finish. I wanted perfection. I wanted my work to be animated by the forces and tensions that animate the world. There was simply too much for one man to do. Others will follow. One man will study anatomy. Another the motions of the stars. Another the laws of beams and falling bodies. Another optics. Another the flow of air and water…”

We stared into the dancing flames.

“One day man will take his flight — that great bird. One day the world will fill with his knowledge and his fame. He will soar, higher than the crags, into the firmament.”

I asked: “What do you consider your greatest work?”

He reflected, then answered: “Perhaps I will be remembered because I have no great work. The painter is not worth praising if he is not a universal man. I sought the universal. I scattered myself too thin.”

A cryptic smile flickered upon his mouth, a smile I had seen in one of his portraits.

“All connected,” he whispered. “All connected.”

I have treasured my 365 Starry Nights since I bought it in the 80’s. I just found these musings and am amazed at how beautifully you communicate my feelings about the universe, life, and its neverending/neverbeginning story.

Thank you, Sue