Originally published 29 January 1990

Like most social enterprises, science is organized as a pyramid.

At the top are the Nobel laureates and directors of major laboratories or government programs. Next come the larger number of university department heads and directors of institutional research programs. Then a bulging stratum of tenured PhDs working in university labs, most of them directing the thesis work of graduate students, and project managers at private or government laboratories who hold advanced degrees. At the bottom are the lab technicians, a teeming and generally invisible mass.

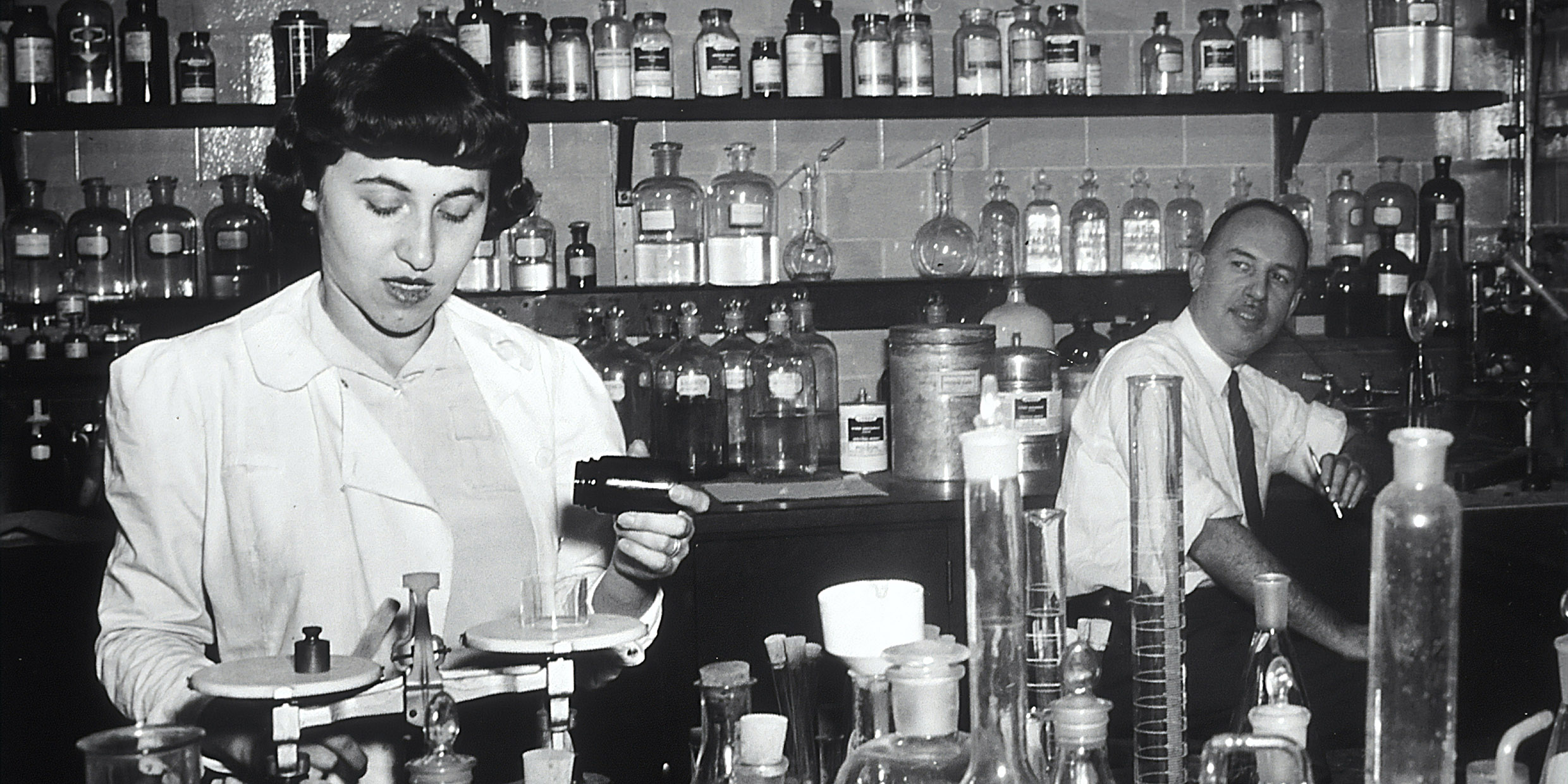

Increasingly, lab technicians are discontented with their invisibility and ask a fair share of the glory that goes with publication of research results. The director of research programs might get his (less commonly, her) name on every paper that originates in the lab, whether or not he directly participated in the research. Technicians who perform the actual dog work of an experiment are at best recognized by an acknowledgment in vanishingly small type at the end of the paper. Graduate students do dog work too, but at least they get their names up front.

If this situation is perceived as an injustice, it is only in recent times that anyone has moved to redress it. The invisibility of lab technicians is deeply rooted in the history of science. The scientists’ claim for sole authorship is based on a traditional distinction between knowledge and skill, and between thought and labor.

Tension from the beginning

In the November – December 1989 issue of American Scientist, sociologist Steven Shapin looks at historical sources of the scientists-technician dichotomy. The tension was already present at the birth of modern science in the 17th century. According to Shapin, it was grounded in social class structure.

Shapin invites us into the laboratory of Robert Boyle, one of the most prolific scientific investigators of his time. By 17th century standards, Boyle’s laboratory was Big Science, a densely populated workplace devoted to the discovery of nature’s truth.

Boyle directed and dictated. Assistants constructed apparatus, prepared chemicals, performed experiments. The place was crammed with crucibles, retorts, air pumps, barometers, thermometers, microscopes, and telescopes, prepared and operated by technicians.

Except no one called them technicians; that term, like the word “scientist,” did not come into general use until the 20th century. They were called amanuenses, laborants, operators, or artificers. The blanket term for these invisible assistants was “servants.”

In British society of the time, servants were those who exchanged their labor for money. They were disenfranchised from taking part in the political life of the nation. The servant’s voice was assumed to be “included in” the master’s voice. In this respect, the servant’s status was the same as that of a married woman who was thought to be “included in” her husband.

Of the many scientific servants Boyle employed, only one is mentioned by name in Boyle’s voluminous writing. That person, Denis Papin, was a medical graduate and a scientific author before he came into Boyle’s service. He planned and organized a great part of the experiments he performed. He even wrote up the results. But Boyle claimed sole authorship. It was, after all, Boyle’s laboratory. Boyle was master.

All of this conforms to the popular image of the scientist as a solitary genius in private contact with his muse. According to this deeply-ingrained myth, scientific truth comes as flashes of insight to knowledgable thinkers, not as the product of collective work or manual skill.

Actual work done by others

Seventeenth-century scientists loudly proclaimed hands-on contact with nature as the only legitimate source of truth, but in practice they were likely to hire others to do the actual mucking about with chemicals and pumps. And they carefully preserved their gentlemanly status by insisting upon the invisibility of assistants.

What does all of this have to do with the practice of science today? Social class distinctions have mostly fallen by the wayside, and scientists are now more likely to admit the collective nature of research. Nevertheless, Shapin suspects that historical arrangements and sensibilities regarding the work of technical assistants are “not wholly irrelevant” to understanding the modern situation.

Perhaps only lab technicians know to what extent the old attitudes persist. Female lab technicians might feel doubly invisible.

In a brilliant recent study (The Mind Has No Sex? Women in the Origins of Modern Science) historian Londa Schiebinger documented the ways women have been excluded from the established image of the scientist as a solitary male researcher. She too claims that historical and cultural conventions continue to shape the course of scientific research and knowledge.