Originally published 20 April 1998

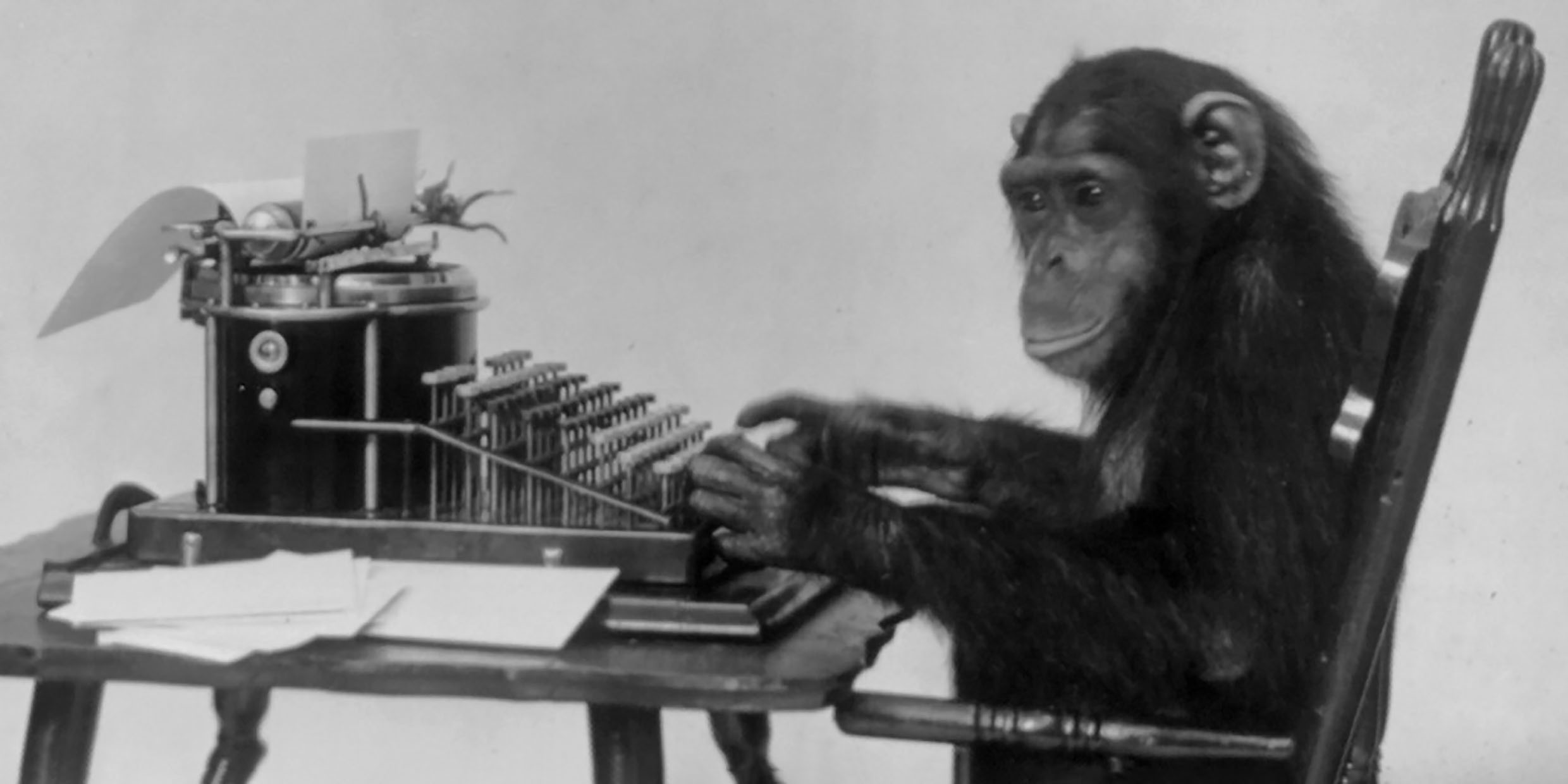

OK, OK already. A thousand monkeys banging on a thousand typewriters for a thousand years could not produce the works of Shakespeare. They might not even produce three sentences: “But soft! What light through yonder window breaks? It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.”

We are hammered again and again with this obvious fact by religiously motivated opponents of evolutionary science, most recently by Harvard-educated Patrick Glynn in a book called God: The Evidence. (I have not read the book: I am relying on an account by author and columnist William F. Buckley, Jr., who has in recent years added his own highly articulate voice to the anti-Darwinian crusade.)

The idea seems to be that Darwinian evolution is based on purely random mutations of the genes, and that randomness by itself will never generate the elaborate order that we see in the natural world, including, of course, ourselves, the paragons and purpose of creation.

Therefore, say these critics of so-called “Darwinian materialism,” the evidence is manifest for Intelligent Design — the controlling hand of an omniscient Creator who guides all things to their destiny.

We’ll get to the controlling hand, but first let’s make it clear that the thousand-monkey metaphor is an inadequate — indeed, perverse — misrepresentation of the Darwinian program.

Yes, there is a random or capricious element in the theory of evolution as it is currently applied. Genes mutate, either because of errors during the hugely complex process of reproducing themselves, or because environmental assaults damage them. There is no denying this; such changes have been exhaustively demonstrated. And for all practical purposes the changes appear haphazard.

But Darwinian evolution is not the willy-nilly accumulation of random mutations. Genetic changes persist or disappear depending on their survival value in a particular environment. This too cannot be doubted; nature is relentless in its harvest of the weak.

If any entity, natural or artificial, is programmed to reproduce itself, and if the program is subject to random mutations and some kind of selection, then evolution is a logical necessity — as many computer experiments have demonstrated.

Living organisms fit that description. The evolution of organisms is not just a theoretical possibility; it is inevitable.

Indeed, it would require the intervention of a divine hand to keep it from happening.

Back to the monkeys. Let’s say that every time a monkey types (by chance) a string of A’s I give it a banana. And I give the other monkeys a boot in the behind. Pretty soon we’d have a lot of monkeys hitting the “A” key incessantly. And no one would call it random. Selection has been at work.

The question then is who or what does the selecting. Does evolution stumble blindly into the future, throwing up ever more finely adapted but utterly contingent and unpredictable species? Or is there a guiding intelligence at work that leads nature to a preordained conclusion?

The National Association of Biology Teachers’s 1995 statement on teaching evolution used to read: “The diversity of life on earth is the outcome of evolution: an unsupervised, impersonal, unpredictable, and natural process.” Late last year, after lively debate, the statement was revised to delete the words “unsupervised” and “impersonal.”

According to Wayne Carley, the association’s executive director, the change was made “to avoid taking a religious position” that might offend believers.

The deletion was appropriate, and may help quiet some of the controversy over the teaching of evolution. Although there is no evidence of “supervision” or “personal intervention” in the fossil record of life, neither can these things be ruled out empirically.

Any personal God who is sufficiently omnipotent to create ex nihilo a universe of hundreds of billions of galaxies, each with hundreds of billions of stars and planet systems and all the rich detail they must contain, could surely fiddle with genetic mutations, or even the radioactive decay of nuclei, with such finesse and inscrutable plan that merely human observers might think them random.

Which is to say, the biology teachers’s original statement went beyond what is scientifically provable or disprovable. Scientists should stick to describing what happens and how it happens, in the way most consistent with the available evidence, and leave alone anything that smacks of ultimate causality or purpose.

By the same token, proponents of Intelligent Design and other non-empirical accounts of creation should stay the heck out of the science curriculum. Such matters, pro and con, belong in the province of philosophy and theology, not biology.

But obviously, we have not heard the end of the thousand monkeys. They have been clattering at their typewriters at least since Darwin’s time, and they are not about to go away.

In the meantime, I for one choose to believe that if I had supervision of a thousand monkeys, not for a thousand years, but, say, a million generations, a sufficient supply of bananas, a durable boot, and the right to decide which monkeys get time off for procreation, sooner or later I would witness a creature who sat at its machine and thoughtfully typed: “Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon, who is already sick and pale with grief that thou her maid art far more fair than she.”