Originally published 18 May 1998

What is the greatest scientific discovery of the 20th-century?

Nuclear energy? The structure of DNA? The theory of digital computation? The Big Bang?

It has been an exceptional century of discovery. Our vision of the universe has been extended by many orders of magnitude outward to the quasars and inward to the quarks. Our understanding of our place in the stream of life and consciousness has been consolidated.

How do we choose one discovery over any other?

The physician Lewis Thomas made a choice. He bluntly asserts: “The greatest of all the accomplishments of 20th-century science has been the discovery of human ignorance.”

The science writer Timothy Ferris agrees: “Our ignorance, of course, has always been with us, and always will be. What is new is our awareness of it, our awakening to its fathomless dimensions, and it is this, more than anything else, that marks the coming of age of our species.”

It is an odd, unsettling thought that the culmination of our greatest century of discovery should be the confirmation of our ignorance. How did such a thing come about?

The discovery of our ignorance followed inevitably from discoveries of the scope and grandeur of the universe.

I begin my course in astronomy at Stonehill College holding in my hands a 16-inch clear acrylic celestial globe spangled with stars. A smaller terrestrial globe is at the center, and a tiny yellow ball representing the sun circles between Earth and sky. This tidy cosmos of concentric spheres was invented thousands of years ago to account for the apparent motions of sun, moon, and stars, and for that task it still works pretty well.

When we thought we lived in such a universe, we could believe that a complete inventory of its contents was possible. The universe was proportioned to the human scale, created specifically for our domicile. Presumably, since it was made for us, the universe contained nothing beyond the ken of the human mind.

Then, in the winter of 1610, Galileo turned his newly-crafted telescope to the Milky Way and saw stars in uncountable numbers, stars that served no apparent purpose in the human scheme of things since they could not be seen by human eyes. It was an ominous hint of the cascading discoveries to come.

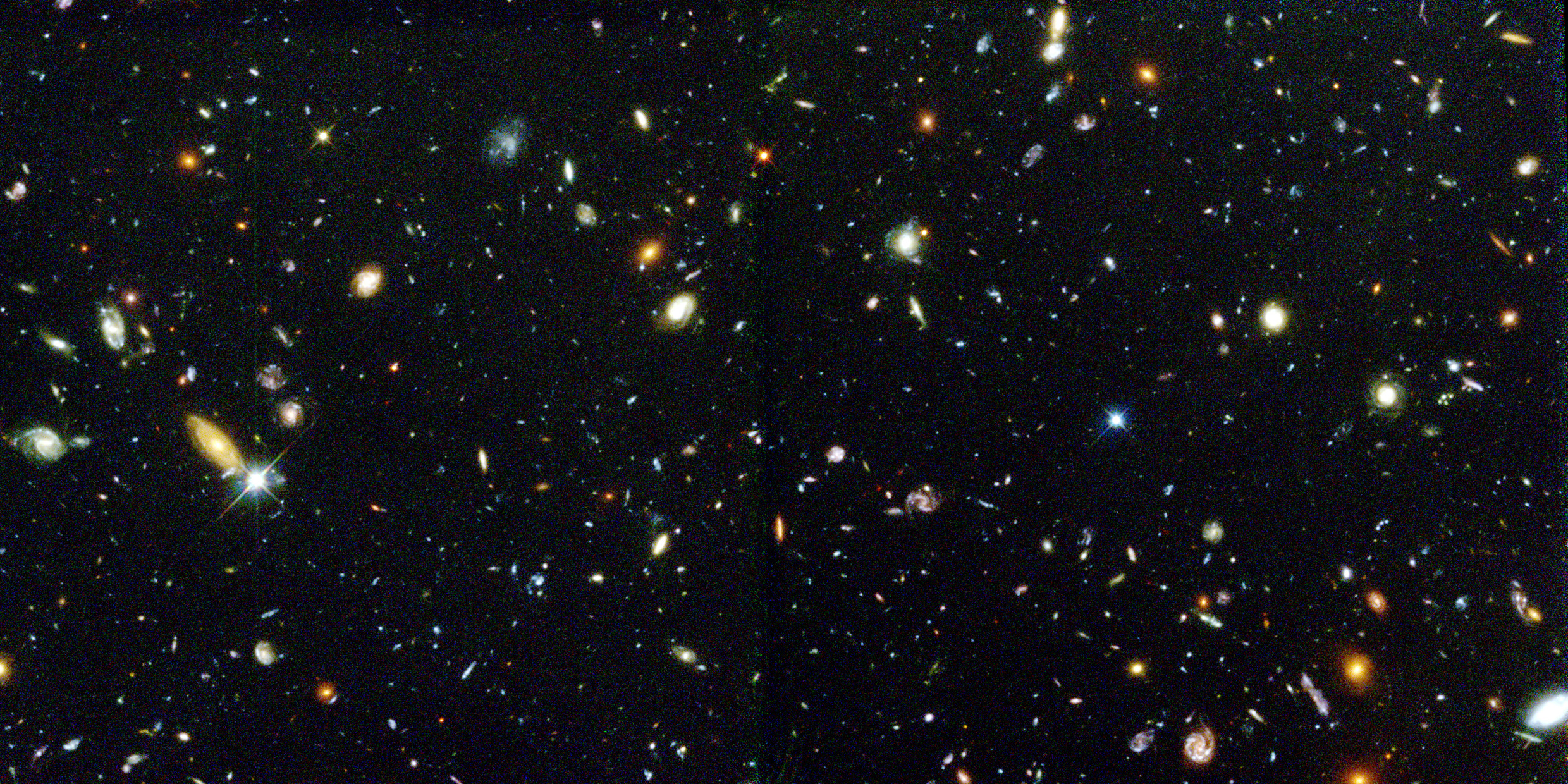

I end my astronomy course with the Hubble Space Telescope’s Deep Field Photograph, a 10-day exposure of a part of the dark night sky so tiny it could be covered by the intersection of crossed pins held at arms length. In this photo are contained the images of several thousand galaxies, each galaxy consisting of hundreds of billions of stars and planet systems.

A survey of the bowl of the Big Dipper at the same scale would show 40 million galaxies.

Galaxies as numerous as snowflakes in a storm! Each with uncountable planets, strange geographies, perhaps biologies, intelligences. To live in such a universe is to admit that the human mind singly or collectively will never be in possession of final knowledge.

Ferris quotes the philosopher Karl Popper: “The more we learn about the world, and the deeper our learning, the more conscious, specific, and articulate will be our knowledge of what we do not know, our knowledge of our ignorance. For this, indeed, is the main source of our ignorance — the fact that our knowledge can be only finite, while our ignorance must necessarily be infinite.”

How do we react to this new and humbling knowledge? That depends, I suppose, on our temperaments. Some of us are frightened by the vast spaces of our ignorance, and seek refuge in the human-centered universe of the acrylic star globe. Others are exhilarated by the opportunities for further discovery, for the new vistas that will surely open before us.

It is the latter frame of mind that drives science. The physicist Heinz Pagels wrote: “The capacity to tolerate complexity and welcome contradiction, not the need for simplicity and certainty, is the attribute of an explorer. Centuries ago, when some people suspended their search for absolute truth and began instead to ask how things worked, modern science was born. Curiously, it was by abandoning the search for absolute truth that science began to make progress, opening the material universe to human exploration.”

The discovery of our ignorance should not be conceived as a negative thing. Ignorance is a vessel waiting to be filled, permission for growth, a foundation for the electrifying encounter with mystery.

When the present century comes to an end, we can claim with optimism that we know both more and less than we knew at the beginning: More because our inventory of knowledge has been greatly expanded, less because the scope of our ignorance has been even more greatly realized.

Timothy Ferris writes: “No thinking man or woman ought really to want to know everything, for when knowledge and its analysis is complete, thinking stops.”

It’s so easy to fall back into a small, narrow, human-centered world for many of us. Accepting the fact that we live in a huge, indifferent universe, one “not made for us” is a tough prospect for millions of people. Glad I’m not one of them! 😌 Excellent article!