Originally published 14 December 1987

The aftermath of the tragedy continues to unfold. It is a haunting, terrifying story, touched with dreamlike beauty, ending in suffering and death — a moral fable for our times.

On Sept. 13 [1987] two unemployed young men entered a partly demolished radiation clinic in Goiânia, Brazil and removed a cancer-therapy machine. Inside the machine they found a stainless steel cylinder, about the size of a gallon paint can, which they sold to a junk dealer for $25.

The cylinder contained a cake of crumbly powder that emitted a mysterious blue light. The junk dealer took the seemingly magical material home and distributed it to his family and friends. The dealer’s six-year-old niece rubbed the glowing dust on her body. It is easy to imagine that she might have danced, glowing eerily in the sultry darkness of the tropic night, like an enchanted elfin sprite.

The dust was caesium-137, a highly radioactive substance. The girl is dead of radiation sickness. More than 200 people were contaminated by the glowing powder. Others have died. A panic has gripped the region. The final toll of human suffering can only be guessed.

The image of the luminous little girl won’t go away. According to reports, she was not the only child who rubbed the magical dust on her body, like carnival glitter.

A story of beauty and death

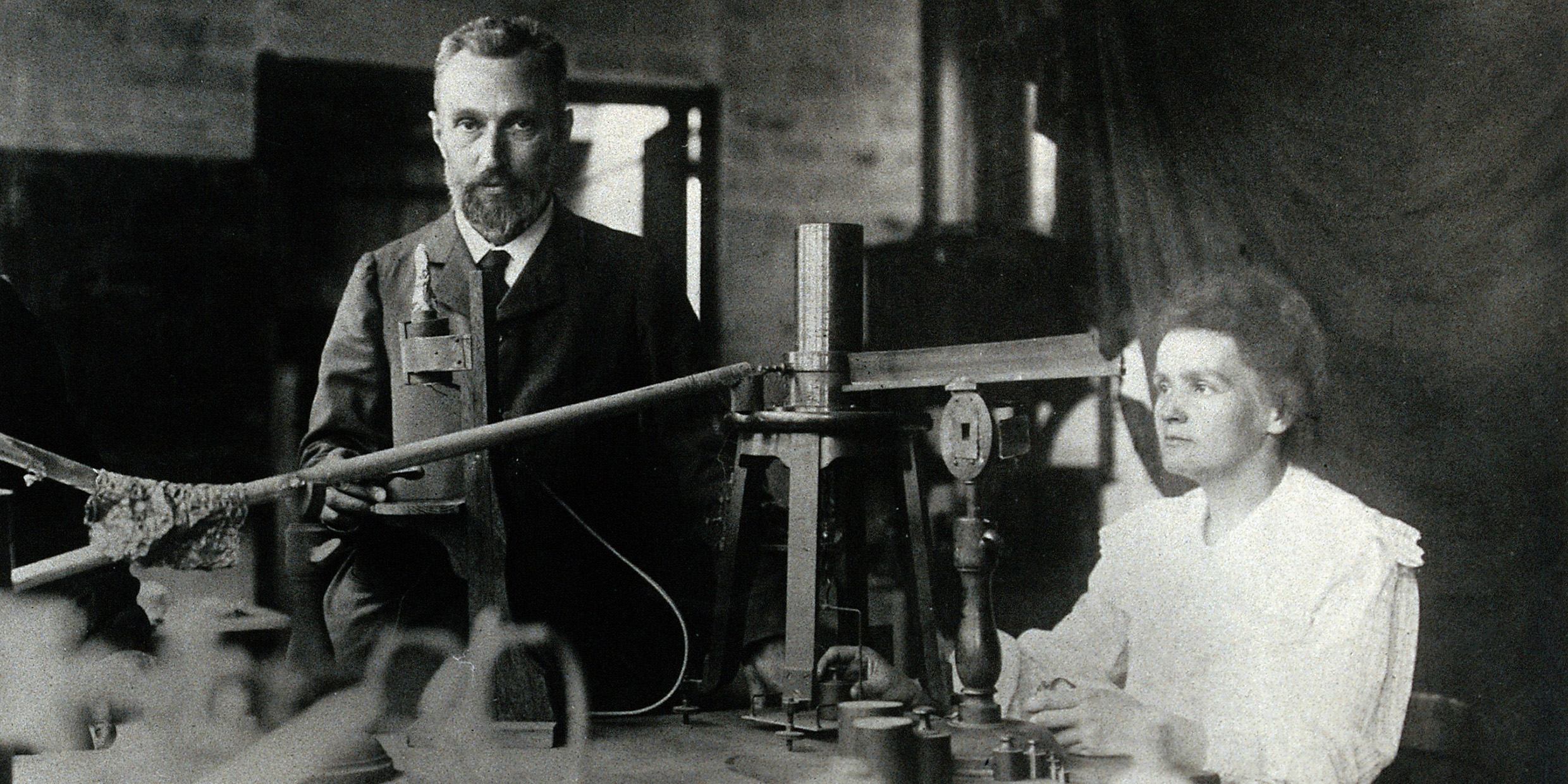

The story recalls another that took place 85 years ago — another story that began in beauty and ended in death, another tale of our ambivalent relationship with radiation. It is a story of Marie and Pierre Curie, the discoverers of radium, as told by their daughter Eve. I have paraphrased what follows from Eve Curie’s biography of her mother.

The story begins at nine o’clock in the evening, at the Curies’ house in Paris. Marie is sitting at the bedside of her four-year old daughter Irene. It is a nightly ritual; the child is uncomfortable without her mother’s presence. Marie sits quietly near the girl until the restless young voice gives way to sleep. Then she goes downstairs to her husband Pierre.

Husband and wife have just completed an arduous four-year effort to isolate from tons of ore a tiny amount of the element that will win them fame. The work is still on their minds: the laboratory, the workbenches, the flasks and vials. “Suppose we go down there for a moment,” says Marie.

They walk through the night to the laboratory and let themselves in. “Don’t light the lamps,” says Marie in darkness.

Before their recent success in isolating a significant amount of the new element, Pierre had expressed the wish that radium would have “a beautiful color.” Now it is clear that the reality is better than the wish. Radium is spontaneously luminous! On the shelves in the somber laboratory the precious particles of the element in their tiny glass receivers glow with an eerie blue light.

“Look — Look!” Marie says.

She sits down in darkness and silence, her face turned toward the glowing vials. Radium. Their radium! Pierre stands at her side. Her body leans forward, her eyes attentive; she takes up again the posture that had been hers an hour earlier at the bedside of her child.

Eve Curie called it “the evening of the glowworms.”

Deadly discovery

The discovery won fame for the Curies. By the middle of the first decade of this century there had begun what can only be called a radium craze. A thousand-and-one uses were proposed for the material with the mysterious emanations.

The curative properties of a radium solution — “liquid sunshine” — were widely touted. Since it was known that radium killed bacteria, suggested uses included mouthwashes and toothpastes. Spas with traces of radium in the water became popular.

Entertainers created “radium dances,” in which props coated with the fluorescent salts of radium glowed in the dark. It is said that in New York people played “radium roulette,” with a glowing wheel and ball, and refreshed themselves with luminescent “cocktails” of radium-spiked liquid.

The most important commercial application of radium was in the manufacture of self-luminous paint, widely used for the numerals of watches and clocks that could be read in the dark. Hundreds of women were employed applying the luminous compound to the dials. It was a common practice for them to sharpen the tips of their brushes with their lips. Many of these women were later affected by anemia and lesions of the jawbone and mouth, and a number of them died.

By 1930, the physiological hazards of radioactivity were recognized by the medical profession, and the reckless misuse of radium had mostly ceased. But, the mysterious emanations — which, properly used, can be an effective treatment for cancer — had taken their toll. Marie Curie herself died of radiation-induced leukemia, with cataracts on her eyes and her fingertips marked by sores that would not heal.

Like many of nature’s gifts, radium proved to be a mixed blessing.

The poet Adrienne Rich has described Marie Curie’s death this way:

"She died a famous woman denying

her wounds

denying

her wounds came from the same source as her power."*

* Excerpt from “Power,” reprinted from The Fact of a Doorframe, ©1984 Adrienne Rich, with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton and Co., Inc.