Originally published 27 December 1993

I’ve been thinking about Lewis Thomas.

Thomas died [in 1993] at age 80. He was a distinguished physician, medical researcher, and administrator. It is for his essays that we remember him best, collected in books such as Lives of a Cell and The Medusa and the Snail.

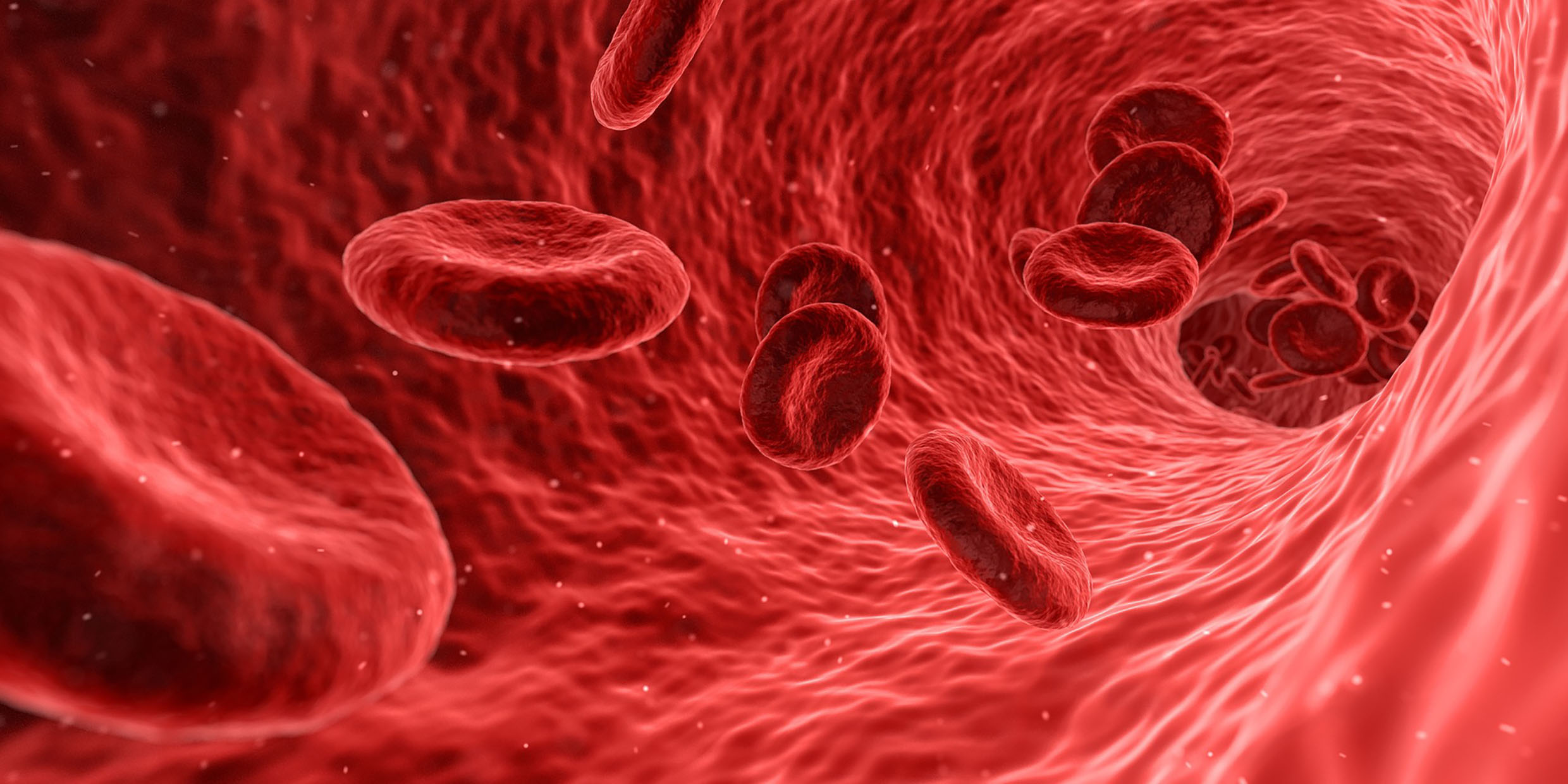

The disease that killed him is called Waldenstrom’s disease. It is an abnormal proliferation of lymphocytes — the white blood cells that are part of the body’s immune system — and plasma cells. These cells in turn produce an excess of the proteins that make the blood viscous. Too much viscosity leads to weakness and death.

He was a victim, then, of cells run amuck, this poet who sang the praise of cells. It is as if Audubon had been pecked to death by birds, or Thoreau had drowned in Walden Pond. Thomas would have been keenly aware of the irony.

Indeed, it was his belief that our bodies are not so much entities in themselves as they are collaborations of cells with existences of their own. “We are shared, rented, occupied,” he wrote of the trillions of individual cells that fused their interests into a consortium named Lewis Thomas.

Each of those trillions of cells is itself a consortium. It is now widely held by biologists that various compartments of human cells — the mitochondria, centrioles, and basal bodies — are themselves more ancient entities that have evolved a symbiotic relationship, each bringing to our complex cells their own genetic contribution, a pinch of DNA and RNA from a time when the Earth was awash in creatures as simple as uncompartmented bacteria and viruses, and nothing else.

This business of living together was a constant theme in Thomas’ writing, a lesson learned from the simplest creatures on Earth. There are no such things as solitary creatures on this planet, he believed. No cell, no part of a cell, can live alone. Every creature is connected and dependent upon the rest.

Bacteria live “by collaboration, accommodation, exchange, barter,” wrote Thomas. They live on each other, and in each other. The marks of identity, distinguishing self from non-self, have long since been blurred.

What applies to bacteria also applies to ourselves, and to the entire biosphere of Earth. In Thomas’ view, all of life is a blur of collaboration, accommodation, exchange, barter.

Of his own cells, he wrote: “I like to think that they work in my interest, that each breath they draw for me, but perhaps it is they who walk through the local park in the early morning, sensing my senses, listening to my music, thinking my thoughts.”

Only a few weeks before his death, the New York Times Magazine profiled Thomas. The article by Roger Rosenblatt was accompanied by a full-page, full-face portrait of Thomas. It is a haunting photograph of a man who knows that he stands at the threshold of death, who knows with the objectivity of a scientist that the consortium of cells that is himself is about to go bust.

The eyes are blank and watery, the lips pinched. One can almost count the cells in the pores and age marks of the skin, in the stubble of whiskers, in the tangle of brows and lashes. I have stared long at the portrait, immersed in its melancholy, searching for the secret of Thomas’ generous optimism. Here is a man who thought of himself as an antheap of cells, and now the antheap is about to be kicked over.

He was not without hope for a kind of immortality. Rosenblatt asked him, “If you’re so sure that there’s no afterlife, why aren’t you just as certain that the end is an absolute end?” He answered: “For one thing, our individual coming to an end may have some connection with the continuity of the species. It may be as important for us to die as it is for plant life to die. So we die and live in our successors.”

What Thomas wanted from life was to be useful: “The thing we’re really good at as a species is usefulness. If we paid more attention to this biological attribute, we’d get a satisfaction that cannot be attained by goods or knowledge.”

Usefulness, he believed, affects succeeding generations in a kind of lingering immortality.

Certainly, Thomas was useful. In contributing as a physician to the health and well-being of his fellow men and women. In writing essays of a cheerful, optimistic humanism. In being one of the most effective philosophers trying to heal the schizoid character of our culture: imminent (“scientific”) six days of the week, and transcendental (“religious”) during the dark hours of the nights and on Sunday.

This dichotomy made no sense to Thomas. Deep in the minutia of his science, he discovered a sustaining source of awe and wonder. Because he had the courage to accept the blurriness of his self, he was rewarded with mystic’s view of the wholeness of creation.