Originally published 23 July 1990

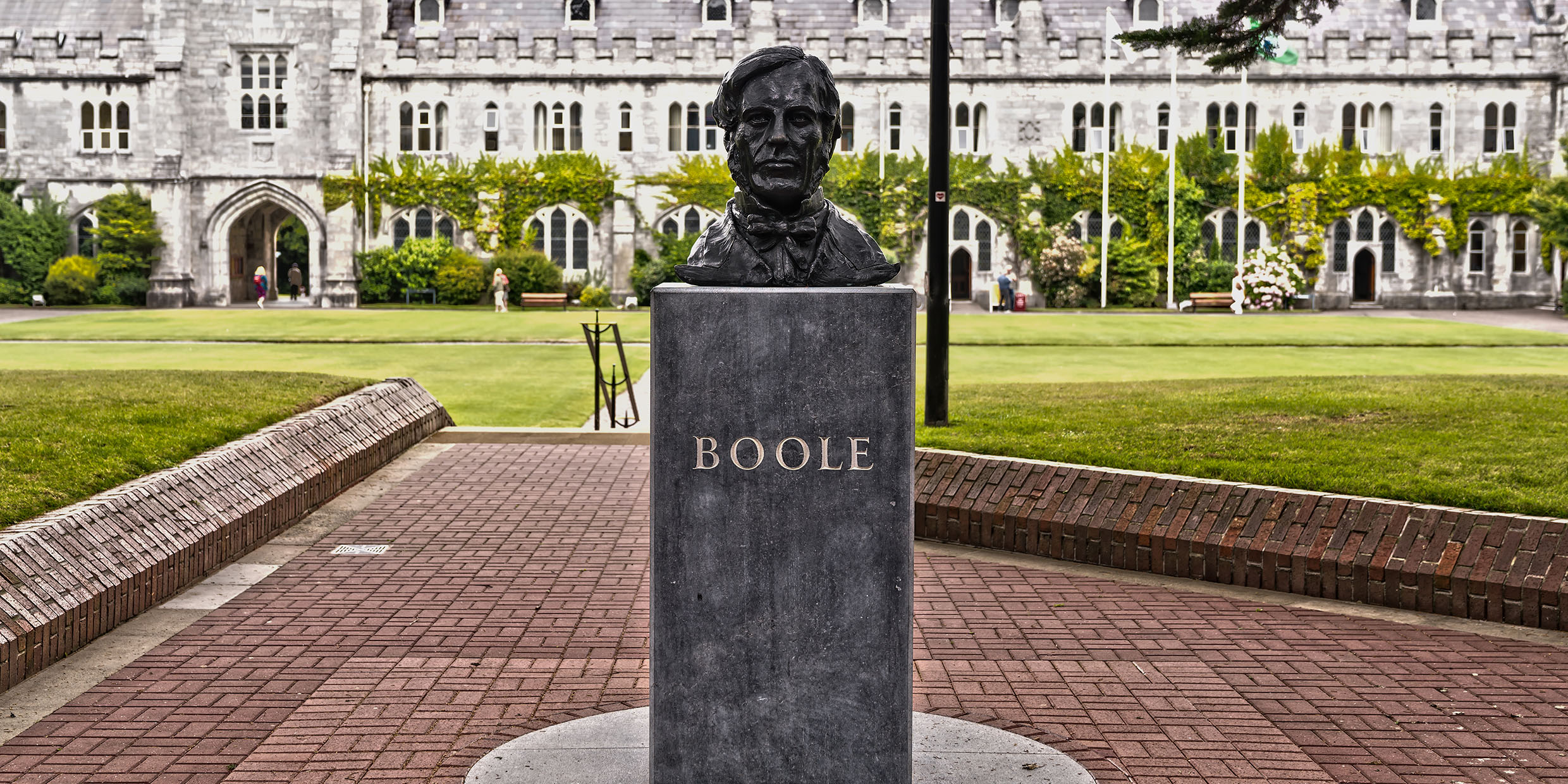

Inside the entrance of the Boole Library, at Ireland’s University College in Cork, the watchful eyes of George Boole gaze down on visitors from the stern but kindly portrait that hangs in a place of honor.

The name will be familiar to every computer scientist. George Boole’s algebra of logic underlies the design of all modern computers. The memorial plaque on his home in Cork boldly calls him “the father of computer science.”

That’s a claim to fame sufficient for anyone, but the story of George Boole—and his family — is extraordinary for other reasons.

In two ways Boole’s story illustrates the power of the human mind to escape the commonplace. With nothing but pluck and hard work the poor son of a shoemaker lifted himself to a professorship of higher mathematics. And in his mathematical researches, Boole freed algebra from its long servitude to arithmetic. No less an authority than Bertrand Russell credited Boole with the discovery of pure mathematics.

Inspiration to Einstein

Russell’s appraisal may be an exaggeration, but no one underestimates Boole’s contribution to the 20th century. His mathematics of invariants became part of the inspiration for Einstein’s theory of relativity. And the “Laws of Thought” which Boole published in 1854 provide the language for digital computing.

Boole was born in Lincoln, England, in the year of Waterloo, into poverty no less restricting than that of his American contemporary Abraham Lincoln. In 19th-century America, a boy might be encouraged to better his position in life, but in class-bound Britain it was expected that sons or daughters of the lower classes should stay uncomplainingly in their places.

Boole wanted out, but with no clear idea where he could go. With no education beyond primary school, Boole taught himself Latin, Greek, French, and German. His father, a man of wide-ranging curiosity, inspired Boole to study mathematics and natural philosophy. At the age of 19, the precocious youngster opened his own school at Lincoln.

Boole learned mathematics by reading (in French) the works of the great French masters, Lacroix, Laplace, and Lagrange, plodding by candlelight through horrendously demanding texts, forced to invent for himself all of the mathematical preliminaries he had never learned in school.

Perhaps because he was self-taught, Boole noticed things about the symmetry and beauty of mathematics that the great mathematicians had missed, most notably the germ of the theory of invariance, which later became the basis for Einsteinian relativity.

The originality of Boole’s work was soon recognized, and in 1849 he was appointed Professor of Mathematics at the newly established Queen’s College in Cork, now University College, where he remained for the rest of his life. In 1854 he published the work for which he is now chiefly known, An Investigation of the Laws of Thought.

The gist of Boole’s contribution was to recognize that the symbols of algebra, such as X, Y, + and ×, need not refer only to numbers or operations on numbers. Boole applied them to the terms and categories of human thought.

His free-ranging algebra eventually become the basis for the theory of digital computers, but in the short run it helped liberate mathematics from the tyranny of numbers. After Boole (and his contemporary William Rowan Hamilton), mathematicians felt free to explore abstract worlds of their own invention.

Boole died at age 50, only 10 years after the publication of his great book, leaving behind a grieving wife and five young daughters. Anyone who wishes to argue that scientific talent is genetically transmitted can do no better that refer to the daughters of George and Mary Boole.

Talented family

Alicia became a mathematician of considerable talent, like her father self-taught. Lucy was a chemist, the first woman Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Free Hospital, London. Margaret is best remembered for her son, the well-known physicist Geoffrey Ingram Taylor. Mary’s husband, the mathematician Charles Hinton, wrote on worlds of dimensions other than three; he was probably inspired by his mother-in-law and her daughters. Most interesting of all is Ethel, whose life as a political radical, revolutionary, lover of master spy Sydney Reilly, and best-selling novelist deserves a book to herself.

Boole’s wife Mary, herself only 32 at the time of his death, went on to make eccentric but interesting contributions to the psychology of education.

The key word here is liberation. In using his mind to liberate himself from burdens of poverty and class, George Boole helped liberate mathematics from restricting conventions of the past. He also pointed the way for his wife and five daughters to chart unconventional courses at a time when women were expected to act in strict subservience to men.