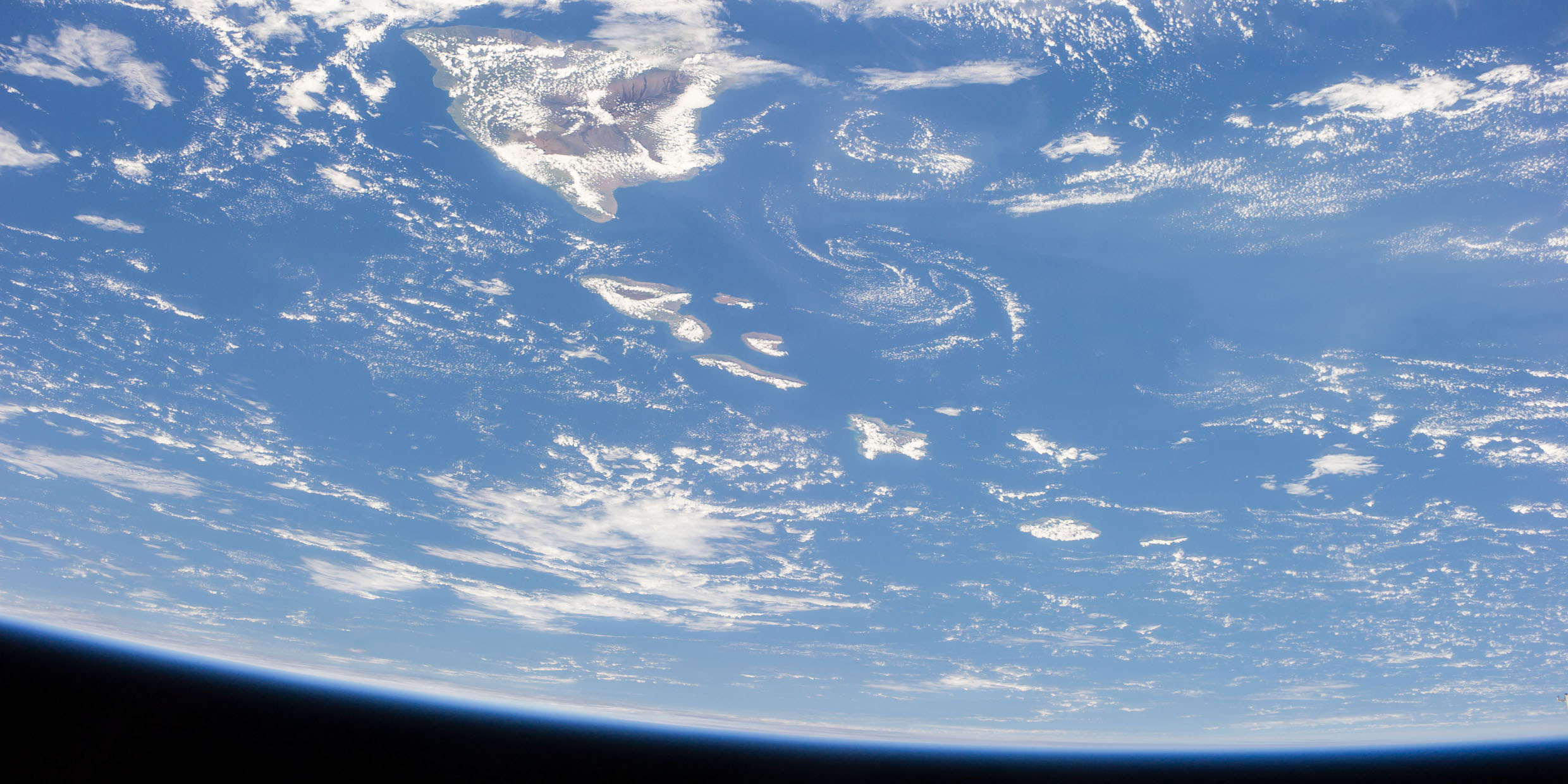

We live on the Water Planet. Nothing confirms this so vividly as a daytime crossing of the Atlantic Ocean at 30,000 feet.

Articles with Earth

Escaping the human scale

When I was a child I owned a picture book that told the story of Christopher Columbus. Several of the illustrations are still clear in my memory. One showed Spanish caravels, with pennants flying, sailing off the edge of a flat Earth into the mouth of a waiting monster. This supposedly illustrated the prevailing view of the shape of the Earth at the time of Columbus.

Reading the rocks

In his book Conversations with the Earth, German geologist Hans Cloos described the moment when he “became a geologist forever.” It did not happen at university. It did not happen with the passing of an exam or the awarding of a degree. It happened one morning in Naples, Italy, when Cloos opened the window of his hotel room and saw the smoking cone of Vesuvius looming above the still-sleeping city. At that moment he had the realization that motivated a lifetime of creative work in geology: The Earth is alive.

CAT scanning Earth

In geology, before the 1960s, we were taught the Earth was “as solid as a rock.” And we were told the surface of the Earth had always looked more or less the way it looks today, the same continents, the same ocean basins. Oh yes, there had been changes on the surface, crinklings and foldings that lifted mountains or cracked the crust, vertical movements mostly, like the wrinkles on the skin of an orange.

Go down, young man, go down

What child has not at some time dreamed of digging a hole to China? Geologists can be excused if they dream the same dream.

A magnetic display

On the evening of September 30, 1961, observers in the northeastern United States were treated to a spectacular display of northern lights — the aurora borealis. It was the first I witnessed (I grew up in the south) and remains the best show of the lights I have seen.

The sands of time

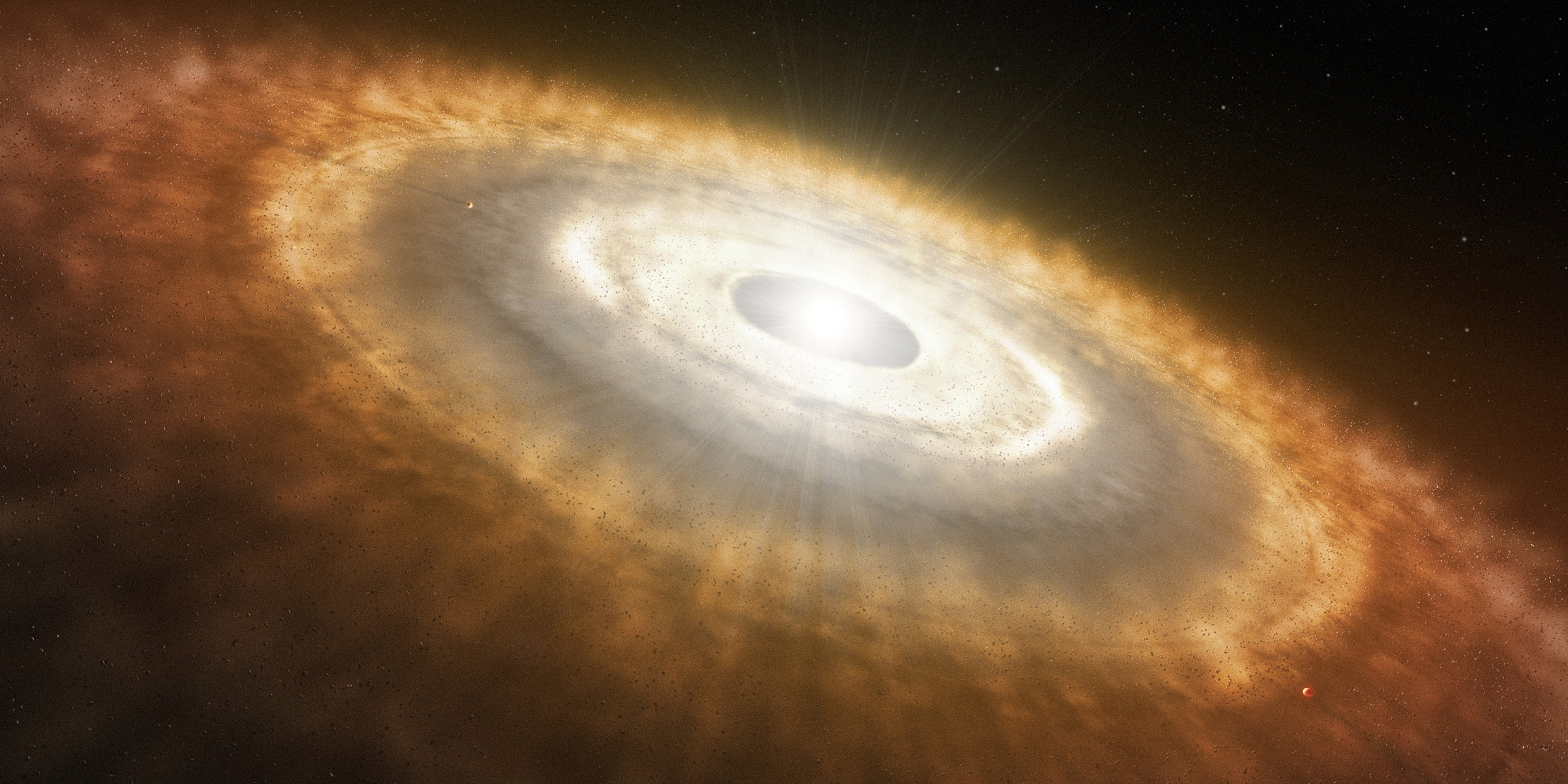

The ingredients of life on Earth were collected by gravity. The hearth that held the tinder and received the spark of life was a small heavy-element planet near a yellow star. Chemistry was the steel and time the flint that struck the spark. For the spark to catch and the flame to grow required not biblical days, but hundreds of millions of years. The solar system has been around for four and a half billion years. That’s time enough for miracles.