At the time Genesis was written, clay was the premier material of artisans. Of it were made containers, tablets for writing, and effigies of animals and men. So what was more natural than for the Creator to do his work in the same medium. According to the author of Genesis, the Lord took up clay into his hands and molded it into the beasts of the field and the birds of the air. And the first man.

Articles with 1987

Curiosity and boundaries

“Scientific curiosity is not an unbounded good.” One does not often hear those words, especially uttered by a scientist. They come from an essay by the octogenarian biochemist Erwin Chargaff in the May 21 [1987] issue of Nature.

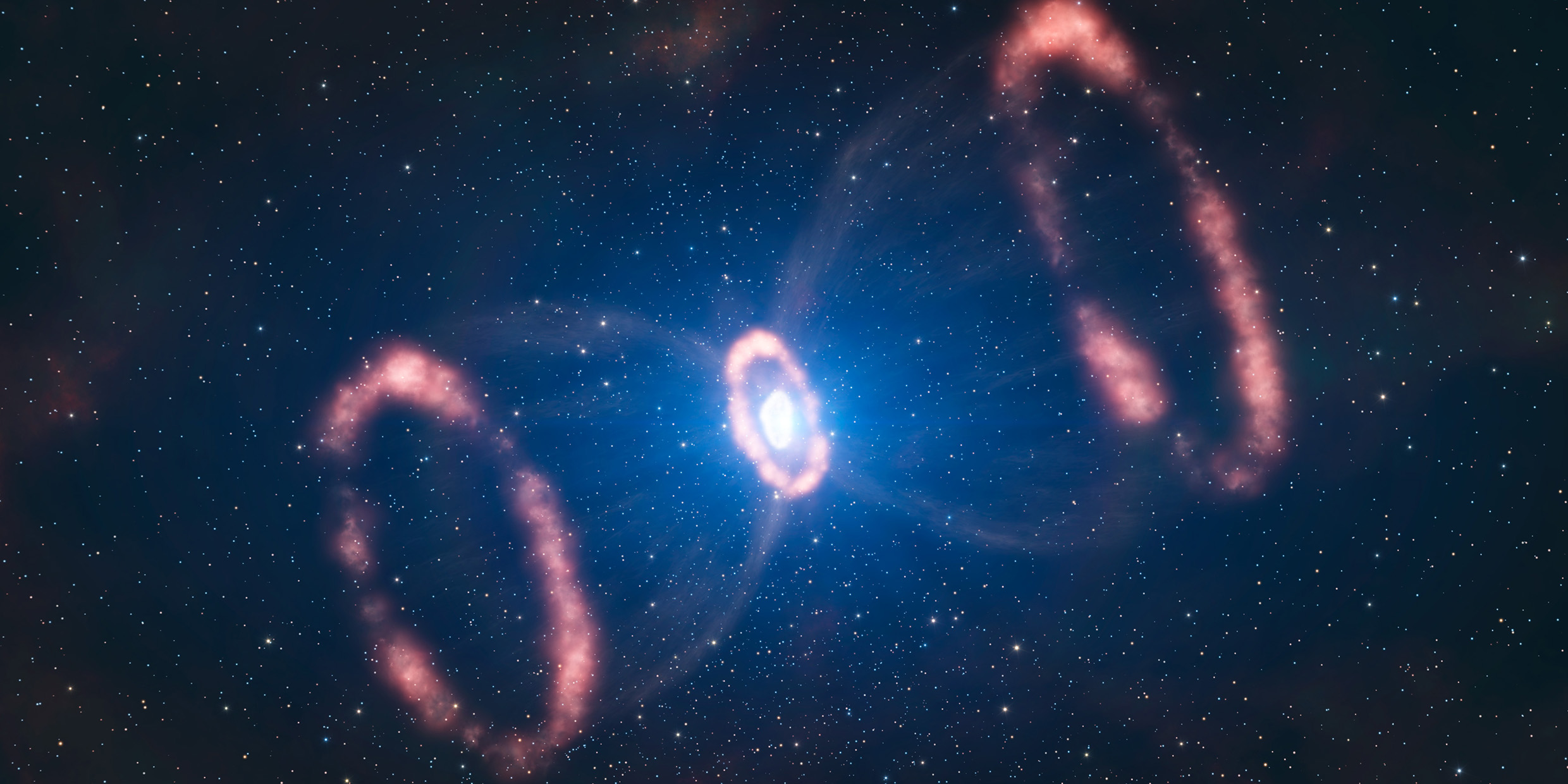

A blowup in the neighborhood?

The February [1987] supernova continues to shine brightly in southern skies. That exploding star is 160,000 light-years from Earth, in a companion galaxy of the Milky Way — and far enough away to pose no threat to us.

The lady’s slipper

Lady’s slipper. Moccasin flower. Squirrel shoes. The scientific name of the plant is Cypripedium, which is Greek for “slipper of Venus.” The early French explorers of North America called it le sabot de la Vierge, “the sabot of the Virgin”; a sabot is a wooden shoe worn by peasants in France.

A superfluity of supers

Consider the word “market.” First, it suffered a certain aggrandizement and became “supermarket.” Then, as compact supermarkets appeared on the scene, a new word was needed. The simplest solution would have been a return to “market.” What in we ended up with instead was “superette,” a curiously self-canceling word made of a prefix and a suffix with nothing in the middle.

Nuclear realities

The world’s first nuclear power station, at Shippingport, Pa., came on line in the late 1950s. After the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Shippingport plant seemed to vindicate our hard-won knowledge of the atom’s secrets. Here at last was a peacetime use for atomic energy. Magazines were full of articles with titles like “The Atom: Our Obedient Servant.” For most of us, it was the dawning of an age bright with promise.

Let’s face it — we’re mediocre

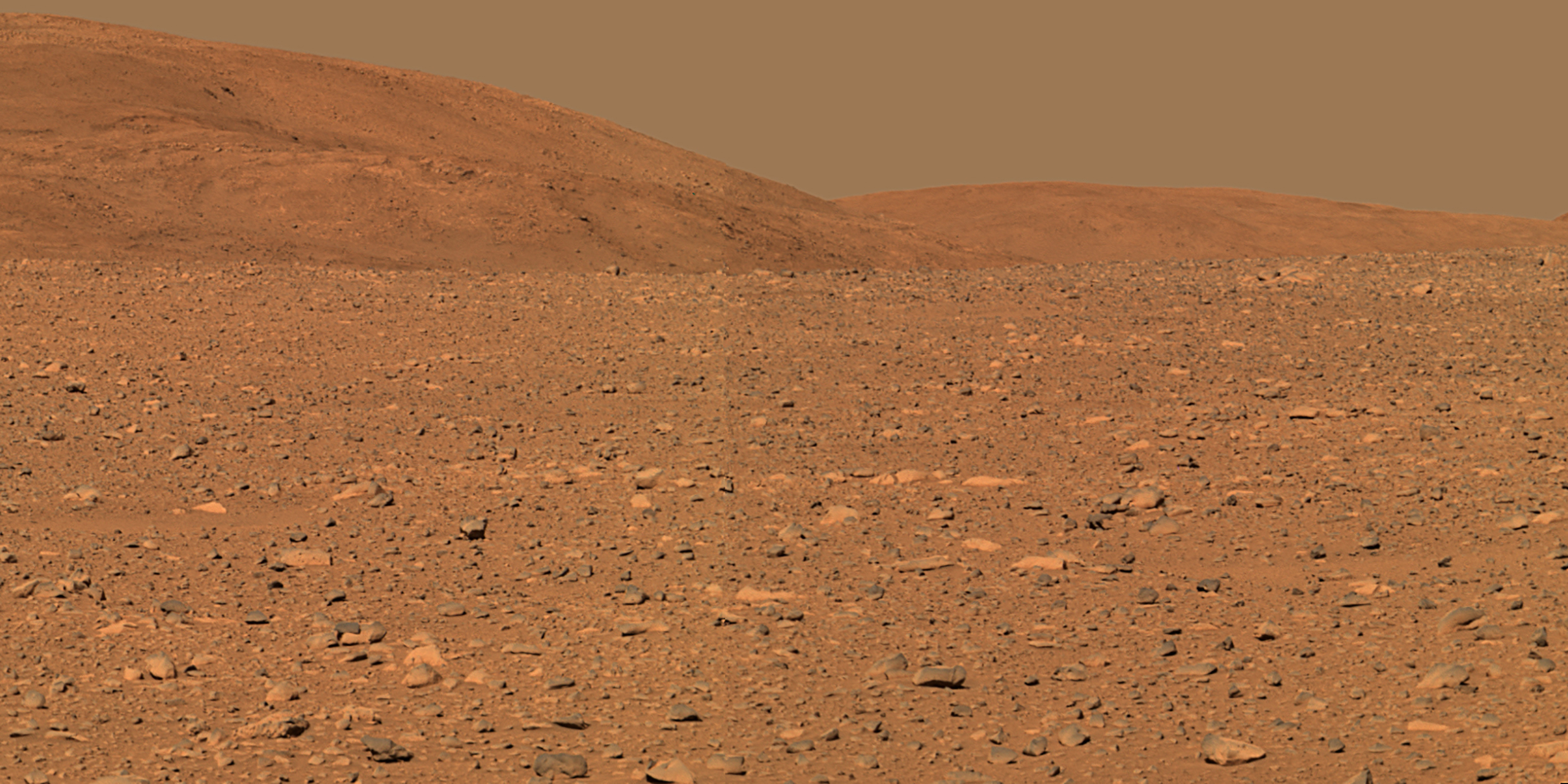

There are as many stars in the Milky Way Galaxy as there are grains of salt in 10,000 boxes of salt. Our sun with its family of planets is a typical “grain.” With their largest telescopes astronomers can see more galaxies than there are boxes of salt in all of the supermarkets of the world, and among them the Milky Way is typical.

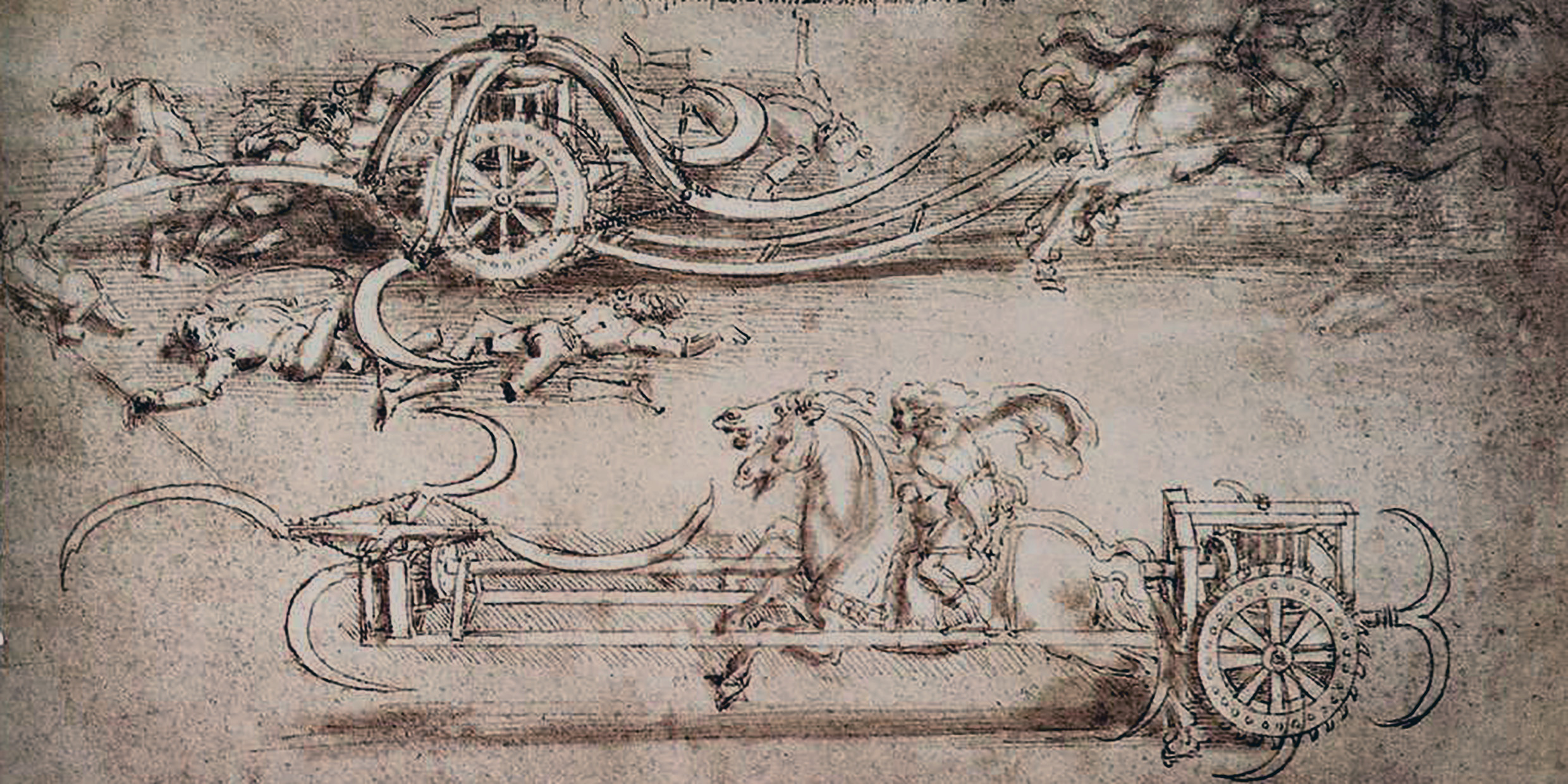

The dark side of Leonardo

Thoreau, Emerson, and Hawthorne all record in their journals a moment when the shrill whistle of the Fitchburg Railroad intruded upon the tranquility of the Concord woods. The track of that railroad passed very close to Walden Pond, and Thoreau especially took note of the way the smoke-belching locomotive disrupted his country reveries.

A gentler scientist

Among the books I remember best from childhood was Jean-Henri Fabre’s “Insect Adventures,” stories translated from the voluminous works of the great 19th century French entomologist and retold for young readers.

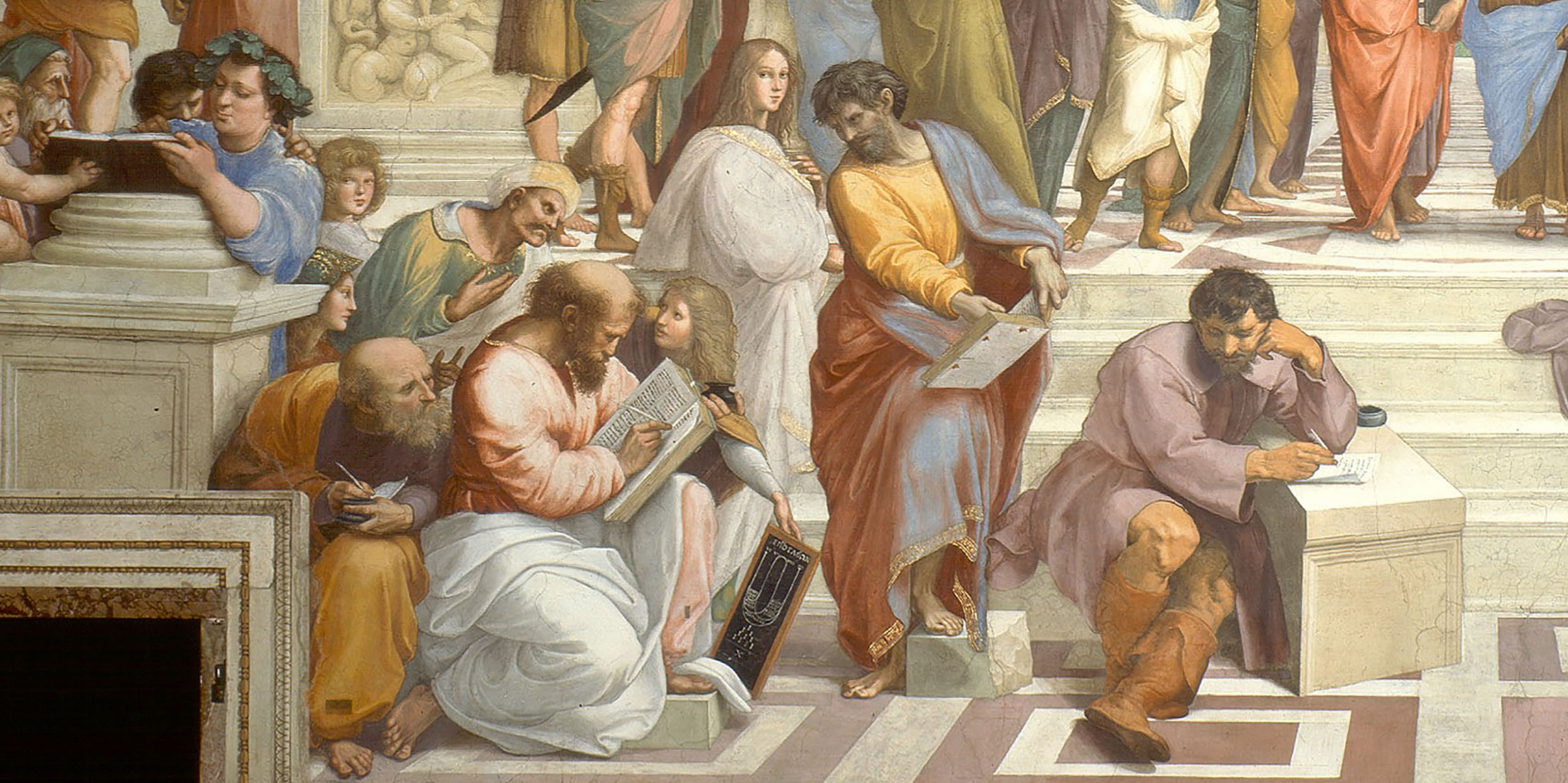

The mutual isolation societies

It has been 30 years since British scientist and novelist C. P. Snow created a stir among educators with his idea of the “two cultures.” According to Snow, “scientific culture” and “literary culture” have become separated by a gulf of mutual incomprehension, often marked by hostility and dislike. Scientists have nothing to say to those who practice or study the arts — and vice versa. Each culture has its own language and agenda. Each is impoverished by ignorance of the other.