“Look at the stars! Look, look up at the skies!” says the poet Gerald Manley Hopkins. “O look at all the fire-folk sitting in the air! The bright boroughs, the quivering citadels there! The dim woods quick with diamond wells; the elf-eyes!”

Articles with 1984

Our reflection in the stars

Thoreau tells us that when he learned the Indian names for things he began to see them in a new way. When he asked his Indian guide why a certain lake in Maine was called Sebamook, the guide replied: “Like as here is a place, and there is a place, and you take water from there and fill this, and it stays here: that is Sebamook.” Thoreau compiled a glossary of Indian names and their meanings. It was like a map of the Maine woods. It was a natural history. The Indian names of things reminded Thoreau that intelligence flowed in channels other than his own.

The earth’s greening

There comes a moment in New England woodlands in the spring when up through last season’s brown leaves and matted pine needles comes the first green. Like a carpet unrolled overnight, suddenly the greedy leaves of the Canada mayflower are everywhere.

Not with a bang but a laugh

A creation myth from the ancient Mediterranean has God bring all things into being with seven laughs. Here is how Charles Doria and Harris Lenowitz translate the first laugh: Light (Flash) / showed up / All splitter / born universe god / fire god. Those lines are two thousand years old, but they aptly describe the modern scientific view of Creation.

Spring’s first mourning cloak

Only a daredevil makes metaphors. To make a metaphor is to walk a tightrope, to be shot out of a cannon, to do aerial somersaults without a net. The trouble with metaphors is you never know when they’ll let you down. You turn a somersault in midair, you reach for the trapeze, and suddenly it’s not there.

A magnetic display

On the evening of September 30, 1961, observers in the northeastern United States were treated to a spectacular display of northern lights — the aurora borealis. It was the first I witnessed (I grew up in the south) and remains the best show of the lights I have seen.

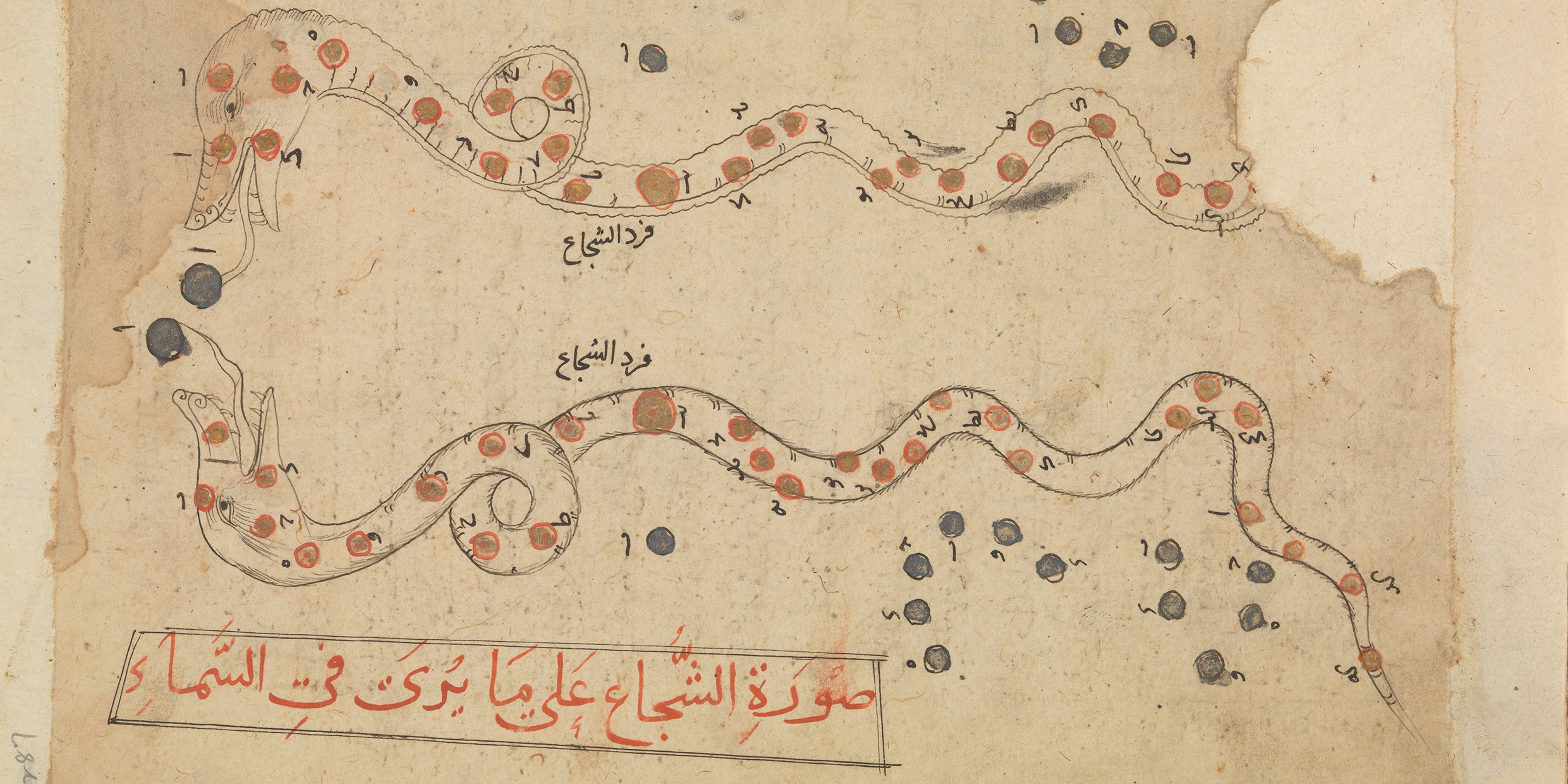

The colorful stars

I have heard it said that the art of observing the night sky is fifty percent vision and fifty percent imagination. Nothing illustrates the truth of the saying better than the colors of stars.

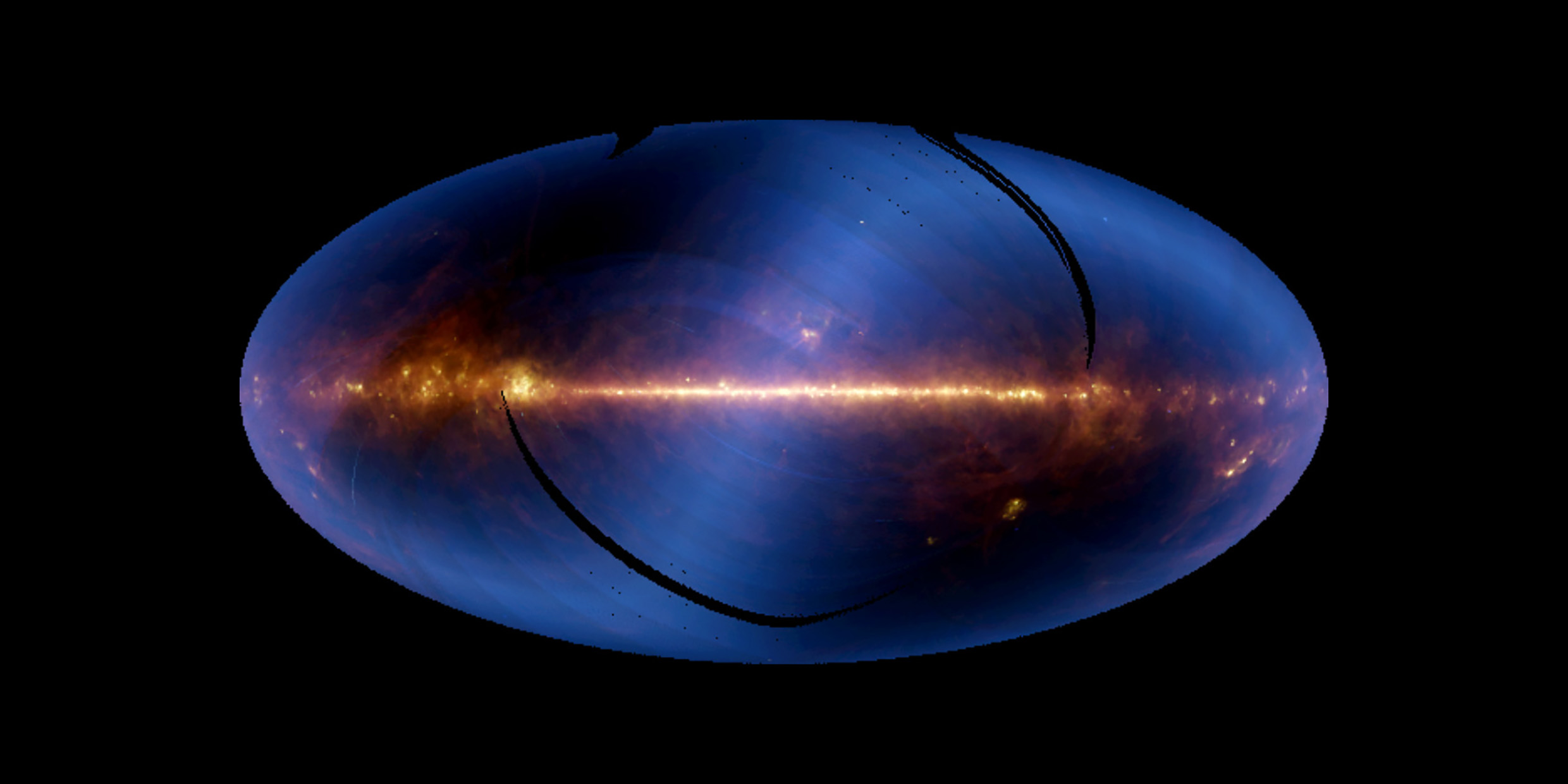

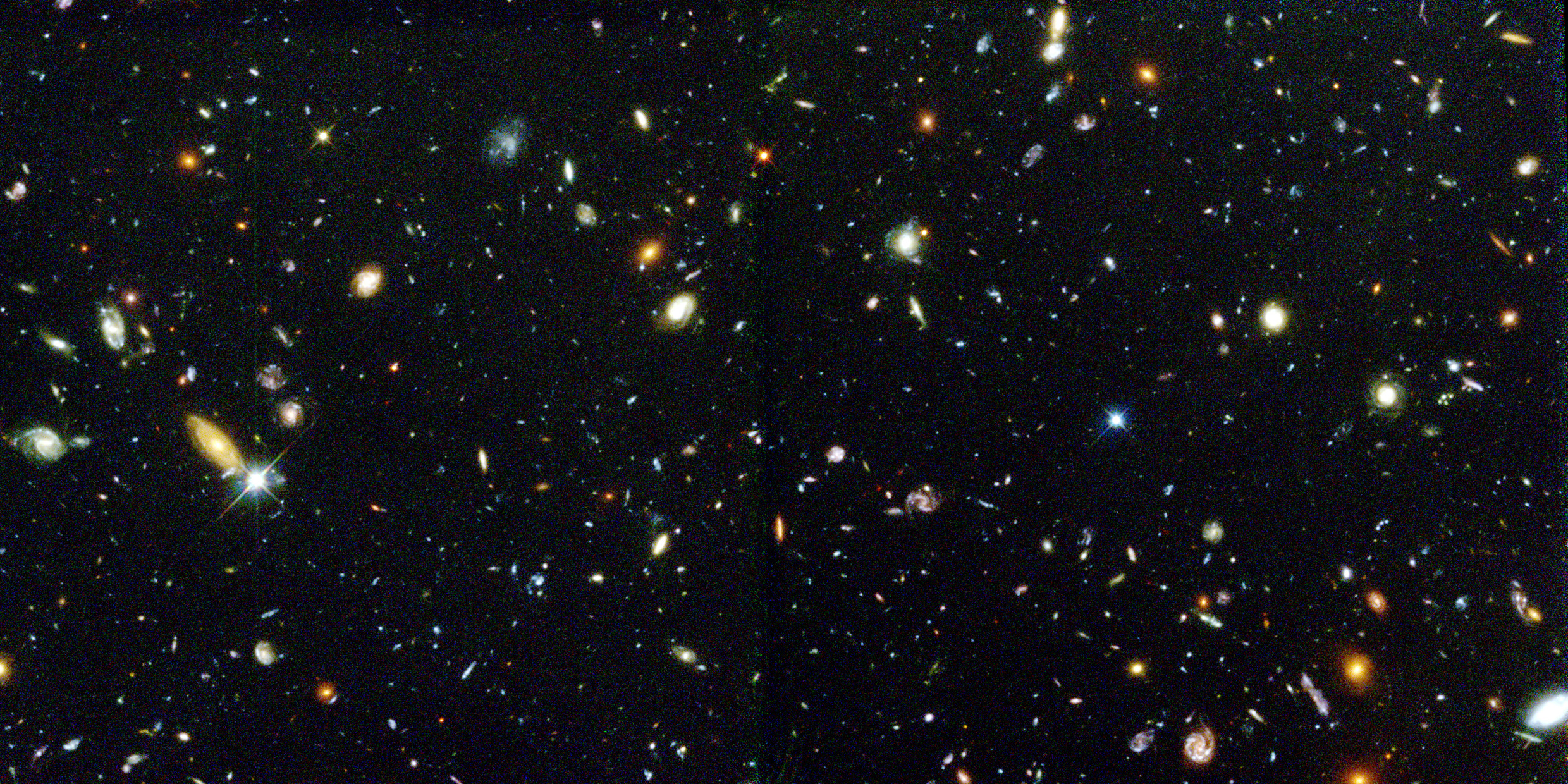

Night’s faintest lights

On the clearest, darkest nights thousands of stars are visible to the naked eye. In addition to stars, there are other wonders available to the careful observer who is far from city lights — star clusters, at least one galaxy, nebulas, the Milky Way, the zodiacal light. But even on the best of nights the typical urban or suburban observer sees only a few hundred stars, and none of the more elusive objects. We have abused the darkness. We have lost the faint lights.

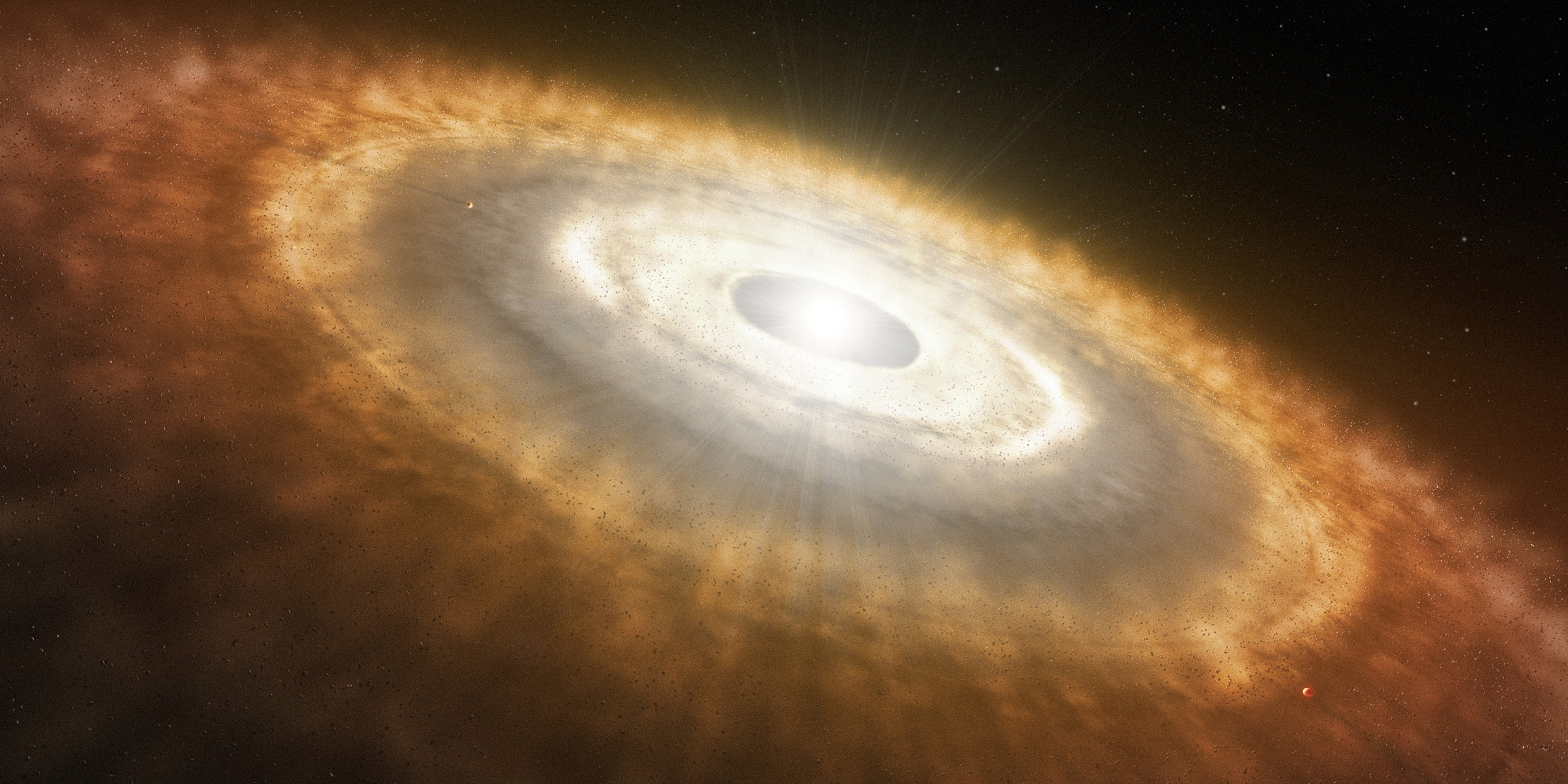

The sands of time

The ingredients of life on Earth were collected by gravity. The hearth that held the tinder and received the spark of life was a small heavy-element planet near a yellow star. Chemistry was the steel and time the flint that struck the spark. For the spark to catch and the flame to grow required not biblical days, but hundreds of millions of years. The solar system has been around for four and a half billion years. That’s time enough for miracles.

Matter’s nature

Since early in the history of western philosophy, matter has been cast as the dross of creation, the chaff, the bottom link of the chain of being, the lowest rung on a ladder of value that reached from the ponderous center of the earth to the highest heaven.