Originally published 18 October 1993

The dodo became extinct 175 years before Lewis Carroll introduced his favorite bird to his favorite little girl in Alice in Wonderland.

Alice has fallen, along with a mouse, sundry birds, and several other “curious creatures” into a pool of her own tears. The Dodo proposes that all should dry themselves by holding a foot race, in which the contestants begin running whenever they wish and run until the Dodo decides the race should end. Everyone wins, everyone receives a prize, and everyone gets quite dry.

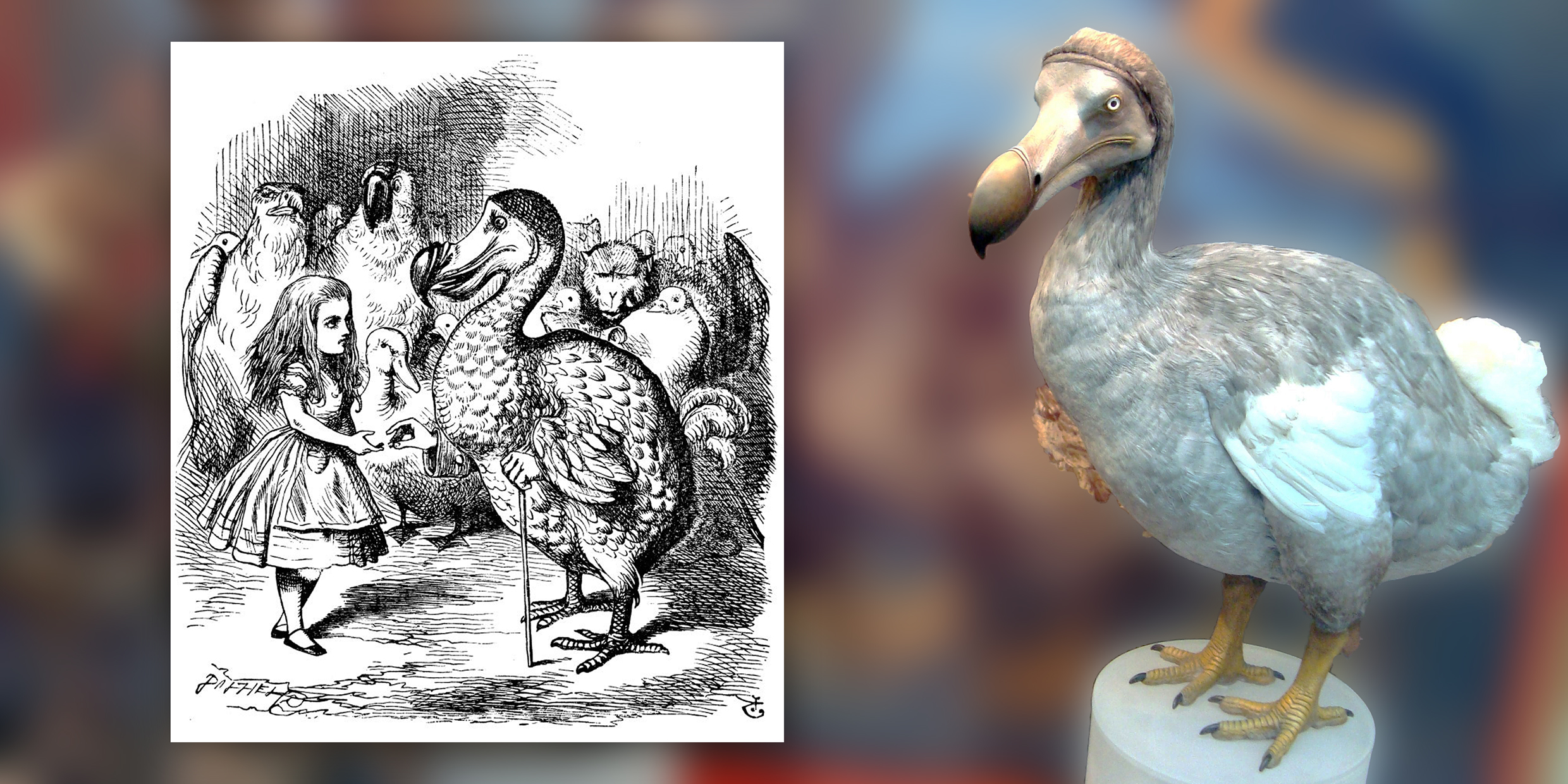

The Dodo is solemn and wise. In John Tenniel’s famous illustration, the bird is a rather distinguished-looking gentleman, not at all the “dumb-dodo” of common parlance. After all, the Dodo of the story was meant to represent Carroll himself, whose real name was Charles Dodgson, and who sometimes stammered his name “Do-Do-Dodgson.”

Carroll and Tenniel have forever fixed the dodo in our imaginations, making it the most famous species of extinct bird.

The dodo was native of the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, where it seems to have evolved from a dove-like ancestor, losing its capacity to fly, and where it lived happily until Europeans arrived in the 16th century. As was often the case with other species, contact with European “civilization” was not a beneficial experience. Within a century of its discovery the hapless dodo had been hunted to extinction.

Portuguese mariners called the bird duodo, meaning “idiot,” from which our name seems to have derived. The Dutch, who came along later, called it dronte, meaning “bloated,” or walghvogel, “disgusting bird.” By all accounts, the dodo was indeed dumb, fat, and disgusting.

And not particularly tasty. The longer a dodo was cooked the tougher and less palatable became its flesh. But, alas for the dodo, it was digestible by hungry sailors, or barely so. Retrospective advice for birds: If you want to survive, don’t be dumb, fat, and flightless on an isolated island halfway across a sea.

A stuffed head of a dodo has somehow survived in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford. It is clear from this specimen that Tenniel tidied up the dodo, making it more handsome than in real life. A beak like a pick ax, a head like a hairy coconut: No more walghvogel visage can be imagined than that afforded by the Ashmolean head. The only biological principle that might have directed this bird’s evolution is survival of the ugliest.

Beyond the Ashmolean head, not much survives of the dodo but a few 17th century sketches, another head, a foot or two, patches of skin, and a few hundred bones. Of these few clues, Bradley Livezy of the University of Kansas has recently attempted to provide the definitive scientific description of the dodo (see Nature, Sept. 23, 1993).

Livezy agrees with the superficially preposterous idea that dodos are anatomically related to pigeons and doves. And he confirms what early explorers and traders reported, that the dodo was unable to fly. The bird was too dronte to get airborne.

What could possibly cause flightlessness to evolve? Well, on pristine Mauritius the dodo was mostly free of predators, at least until the arrival of half-starved European sailors with blunderbusses. The birds survived on seasonal fruits and plants accessible from the ground. Obese birds stored more nourishment in times of plentiful food to help them survive when times were lean. From an evolutionary point of view, it was more advantageous to be fat than to fly.

Livezy tells us that female dodos were two-thirds less fat than males and had shorter bills, but early eyewitness accounts do not suggest that females were any less ugly. Why the dodo evolved to become so much less attractive than its dovish cousins is difficult to say, but dodo standards of beauty were almost certainly different than our own. The most beautiful thing to a dodo was another dodo, and that’s what drives the genes.

Livezy also wonders if the dodo’s curious physique was a result of so-called paedomorphosis, in which the development of a creature stops when it becomes sexually mature, although some parts of the body have not yet achieved developmental maturity. Thus we get, as one observer noted, a bird that resembles “a young duck or gosling enlarged to the dimensions of a swan.” With his sad fixation on little girls, Lewis Carroll seems to have had his own problems achieving sexual maturity, which makes his choice of ornithological persona even more appropriate.

The dodo isn’t the only bird driven to extinction by human predators. There is also the Mauritius Red Hen, the Passenger Pigeon, the Laughing Owl (which did not laugh last), the Four-Colored Flowerpecker, and the ʻōʻō of Hawaii — among many others. Remarkably, even several species of starlings have been driven to extinction, although around my neighborhood it is the starlings that drive humans to distraction.

Of all extinct birds we remember the dodo best, because nothing seems deader than, or as dumb as, and because — as strange as it seems — Charles Dodgson had a stammer.

The Four-colored flowerpecker, once thought to be extinct, was rediscovered in the Philippines in 1992. It remains a critically endangered species. ‑Ed.