Originally published 18 September 1989

Plucky, lucky Voyager 2 is the little spacecraft that could.

Those are the words I wrote three years ago [in 1986] when Voyager 2 completed its spectacular reconnaissance of Uranus and its moons, after a 9‑year voyage from Earth and earlier visits to Jupiter and Saturn. Even then NASA engineers and scientists conceded that Voyager 2 had surpassed their wildest hopes, returning mind-expanding images of unimagined worlds from the depths of space.

Now the plucky, lucky craft has rendezvoused with Neptune, the outermost planet of the solar system, and sent back a stream of information that will cause the astronomy books to be rewritten — once again.

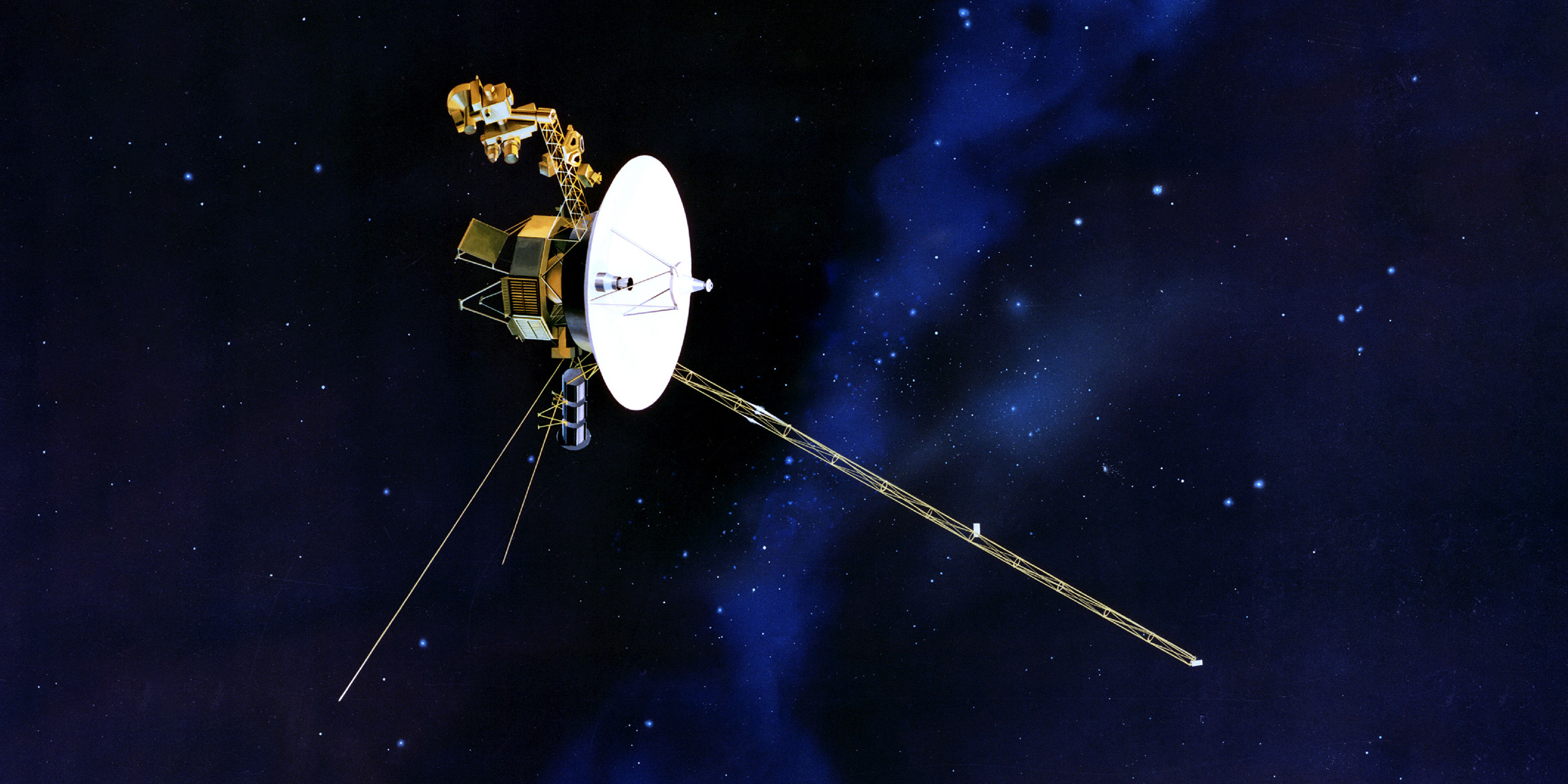

It may seem anthropomorphic to use words like pluck and luck to describe what is after all only about a ton of metal and electronics, but I think not. Voyager 2 is in a real sense an extension of ourselves. Its eyes are our eyes. Its ears are our ears. Its computer chips are jam-packed with our thoughts. It moves with exquisite subtlety in response to our will. Its pluck is our pluck, and its luck is our luck.

Now Voyager 2 heads for the stars and we go with it.

In 40,000 years the plucky spacecraft will pass within a couple of light-years of the star Ross 248. A few hundred thousand years later it will come close to Sirius. By then Voyager 2 will indeed be nothing more than a lifeless chunk of silicon and metal. It will have lost its animate connection to its creators, responding only to the mindless tug of gravity. Blind and deaf, it will drift like a tuft of thistle on stellar winds.

Beyond the solar system

Four spacecraft are now on trajectories that will take them beyond the solar system: Pioneers 10 and 11, and Voyagers 1 and 2. By early in the 21st century we will receive the last radio transmissions from the luckiest of these craft (what the engineers call “loss of signal”). By then, it is to be hoped, other starships will be following the path pioneered by the Pioneers and Voyagers, lively, animate ships designed to extend the range of human thought and action deeper into space, eventually to the environs of other stars.

Space enthusiasts Eugene Mallove and Gregory Matloff have just published a delightful book on the science and technology of starflight; The Starflight Handbook: A Pioneer’s Guide to Interstellar Travel.

They begin by saying: “Starflight is not just hard, it is very, very, very hard!” The problem, of course, is the enormous distances to the stars, and the difficulty of accelerating a ship to a velocity that would make the travel time commensurate with a human lifetime. No one is likely to put a major effort into building a spaceship that won’t reach its destination for 40,000 years.

Manned starflight still exists only on the shadowy borderline between science and science fiction, but, as Mallove and Matloff make clear, it’s not too early to start thinking about the first automated craft that that will traverse the gulf between the stars and return information to Earth. Society might be willing to invest in a journey that lasts only a few hundred years, and propulsion systems for such flights may be available early in the next century.

But then we will face a curious problem unparalleled in human history, what Mallove and Matloff call the “catch up” quandary. When Columbus set out across the Atlantic, he did not hesitate because he feared that later explorers might pass him by in motorized speedboats — or in the supersonic Concorde! But this is exactly the quandary faced by planners of starflight missions.

Let’s assume that by the year 2025 it is possible to build a ship that will reach Alpha Centauri (4.3 lights years away) in 300 years. Given the rate of progress in technology, it seems likely that by 2050 it will be possible to build a craft that can traverse the same distance in, say, 100 years. The earlier ship will be passed by and made obsolete long before it achieved its mission.

Then, of course, by the end of the century it might be possible to make the same flight in 30 years; again, the earlier craft is overtaken. Dilemma: When to launch a flight that will not be made superfluous by new and faster propulsion systems?

People who explore the frontiers of the possible have suggested dozens of hypothetical ways to propel interstellar craft to high velocities. Mallove and Matloff take us through the entire spectrum, from conventional rocketry to solar sails, interstellar ion scoops, fusion ramjets, and spaceships pushed by home-based laser beams.

A ghostly, crewless galleon

A lot of this stuff strikes me as so much Buck Rogers fantasy, but crazy ideas have a way of coming true. This much is certain: Someday, probably before the middle of the 21st century, a live-and-kicking starship will overtake Voyager 2 on its way to Sirius.

As Voyager 237 zips by at one-tenth the speed of light, Voyager 2 will be drifting like a ghostly, crewless galleon, a useless relic of the Columbian age of interstellar exploration. But it will have served a glorious purpose in demonstrating the possibility of starflight. Its cameras, computers, receivers and transmitters, thrusters, gyroscopes, remote sensors, photocells, and all the rest worked well in the hostile environment of space for at least a dozen years, time enough — someday — to make a journey to the stars.

Plucky, lucky Voyager 2 led the way, brimming with confidence.

As of 2020, Voyager 2 is still transmitting, at a distance of over 18 billion kilometers from Earth. ‑Ed.