Originally published 12 April 1993

Bacteria have noses.

Well, not noses exactly, but scent-sensitive spots where a nose should be, up front, heading into the wind.

Janine Maddock and Lucille Shapiro, biologists at the Stanford University School of Medicine, announced this discovery in a [1993] issue of Science. Their report is titled “Polar Location of the Chemoreceptor Complex in the Escherichia coli Cell.” That’s science-speak for “some bacteria have noses.”

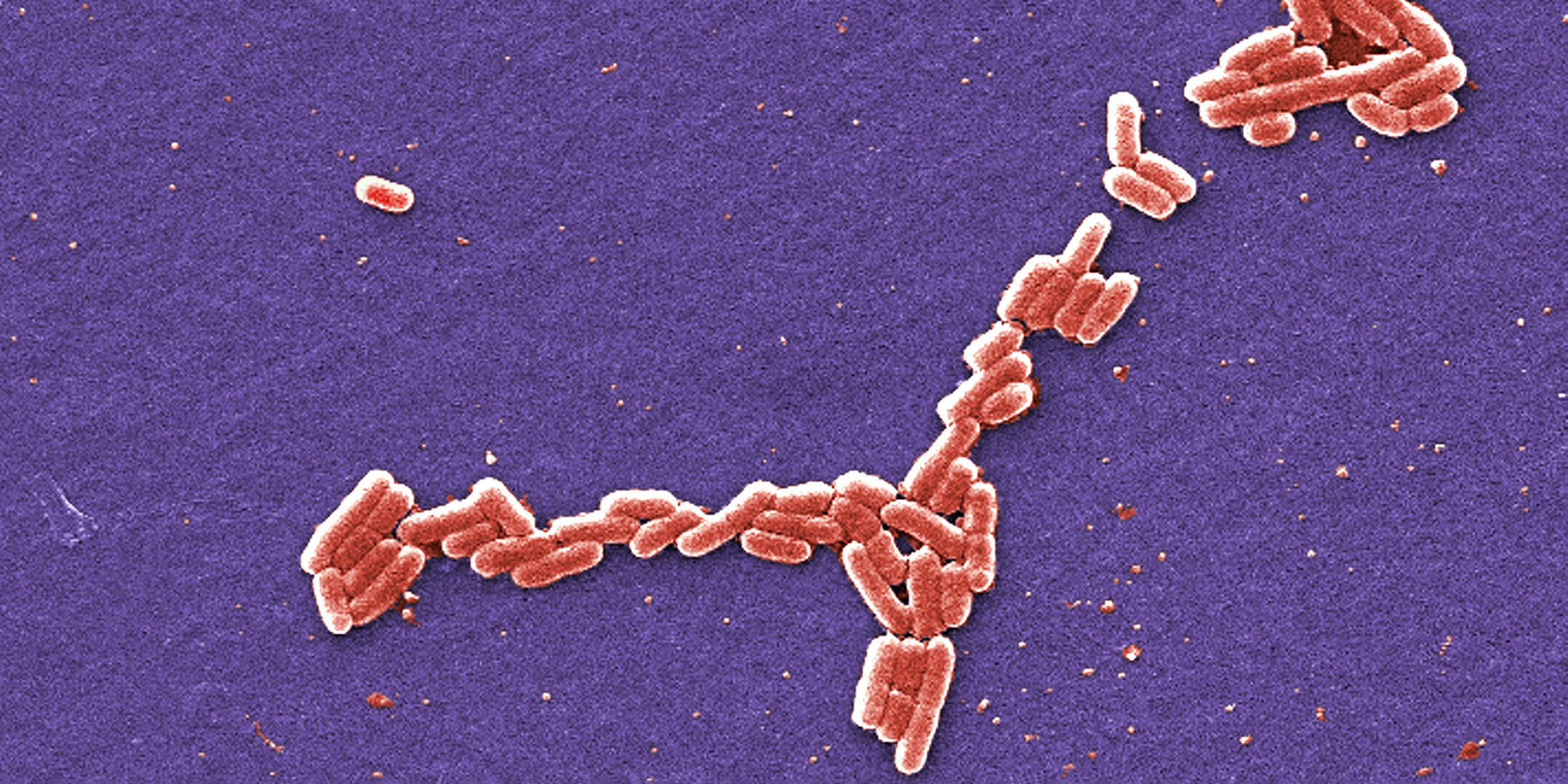

This news comes as a surprise to those of us who imagined bacteria as blobs of featureless protoplasm. Escherichia coli (E. coli for short) is one of the commonest bacteria. A zillion of them live in my digestive track. As far as I knew, they were microscopic sausages of protein with a twist of DNA, a lumpen-proletariat of the germ world.

Now it seems they sniff their way about like bloodhounds. With nutrient-detectors probing ahead, and whiplike appendages churning behind, they wiggle through my gut snapping up food. The little whippersnappers have a more — ah, sophisticated — lifestyle than I ever imagined.

It pleases me to know that my E. coli know where they’re going. I’ve always had an affection for the amoeboid flora and fauna that inhabit my body. Somewhere I read that 10 percent of my dry body weight is made up of invisible organisms — bacteria mostly — that are along for the ride. It’s nice to know they are more than dead weight.

Consider an open stretch of my skin, a shoulder blade, for instance. A close examination might reveal a million bacteria per square centimeter, happily living out their lives on planet Homo sapiens, eating, drinking, moving about, reproducing every 20 minutes or so.

In dark, damp parts of my body — the mouth, the throat — a more plentiful food supply supports a population density a thousand times greater than on the deserts of the skin. These fellows, too, make their living in consonance with mine. They don’t dare cause too much damage or they might kill their host.

Most numerous of all are my intestinal population of E. coli. There are enough E. coli bacteria inside me to reach from Boston to San Francisco if laid end to end. And now that we know they have noses, we know which end is which.

E. coli bacteria took up residence in my body not long after I was born. They are mostly harmless. In fact, they do some good. In exchange for food and shelter they make Vitamin K, which clots blood, and other useful chemicals. They compete against pathogenic bacteria that can cause serious infection.

The relationship between me and my E. coli is called commensal, which means literally “eating at the same table.” As long as we are eating at the same table, I wish them noses. Eyes and ears would do them little good in that dark, muffled place, but a nose can be an asset.

Maddock and Shapiro write: “The subcellular localization of the chemotaxis proteins may reflect a general mechanism by which the bacterial cell sequesters different regions of the cell for specialized functions.” Uh, yeah. What that means, I think, is that E. coli isn’t the simple little blob we thought it was.

In fact, several lines of research have lately suggested a surprising degree of structure in bacteria. They are much, much more than a pinch of jelly in a sack. They sniff. They scoot. They communicate. They might even remember.

A new kind of bacteria, recently discovered in the intestine of a Red Sea fish, is big enough to be seen with the naked eye — about as long as the period at the end of this sentence is wide. Scientists had assumed that bacteria couldn’t be so big because they didn’t have the kind of internal plumbing that could pump nutrients throughout their bodies. Well, apparently there’s more going on inside than we imagined.

Noses and circulatory systems — of sorts. These little guys are positively intricate. It’s nice to have them at my table.

Biologist Lynn Margulis has suggested that the commensal relationship between me and my E. coli is the stuff of evolution. Relationships that begin as commensal may become symbiotic, and eventually two collaborating creatures can become integral components of a new self. If evolution continues for another few million years, says Margulis, the bacteria producing vitamins in our intestines may become part of our own cells. An aggregate of specialized cells may become an organ.

“It is not preposterous to postulate,” she says, “that the very consciousness that enables us to probe the workings of our cells may have been born of the concerted capacities of millions of microbes that evolved symbiotically to become the human brain.”

According to Margulis, this kind of creative symbiosis has been a driving force of evolution.

If she is right, then our entire bodies are collective societies of bacteria that over hundreds of millions of years pooled their DNA and lost the capacity to live on their own. Who knows, maybe our human noses had their origin in phalanxes of bacteria with “polar chemoreceptor complexes” — noses — sniffing together for greater efficiency.