Originally published 8 December 1997

The invasion of the roborats!

From the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena come reports of the first silicon chips that incorporate living brain cells.

Neurophysicist Jerome Pine and his colleagues have found a way to mesh embryonic rat brain cells with silicon circuits, possibly anticipating the day when computers will be fabricated of a combination of living and non-living materials.

Pine’s team etched 16 tiny pits in the surface of a silicon chip. Each pit is connected to the surface by a network of tunnels. A living rat brain cell, or neuron, is placed in each pit. As the cell grows, it sends out dendrites — fingerlike tendrils — that wind their way through the tunnels and make normal synaptic connections with other cells. The tunnels hold the neurons in place on the chip.

The chip is immersed in a nutrient broth that keeps the cells alive.

Once contact between cells is established, electrical activity begins. The cells “talk” to each other, just as they do in a living rat’s brain. Electrical circuits in the silicon chip stimulate the cells and listen in on their communication. The researchers hope the network of cells can be made to “learn” by repeated stimulation.”

So far, the cells on these “neurochips” have been kept alive for only two weeks.

Previously, scientists have attempted to understand neural activity by placing electrodes in a living brain and watching those hugely complicated circuits at work. As pointed out in the journal Science, this is rather like trying to learn electronics by playing around with the inside of a computer.

The approach of the Cal Tech scientists is more like those teach-yourself-electronics kits you can buy for your kids at Radio Shack. Start with 16 rat brain cells, let them establish connections, then watch them do their thing.

This new research is interesting on two fronts: It is an elegant new experimental approach to understanding how brains work; and it suggests ways of building a new class of hybrid electronic devices, partly animate, partly inanimate.

Although practical success is far in the future, it is not hard to imagine hybrid devices consisting of millions, or even billions, of living rat brain cells, anchored in silicon circuits, and taught by repeated stimulation to perform useful tasks.

At which point, the language of computers will expand to include hardware, software, and ratware.

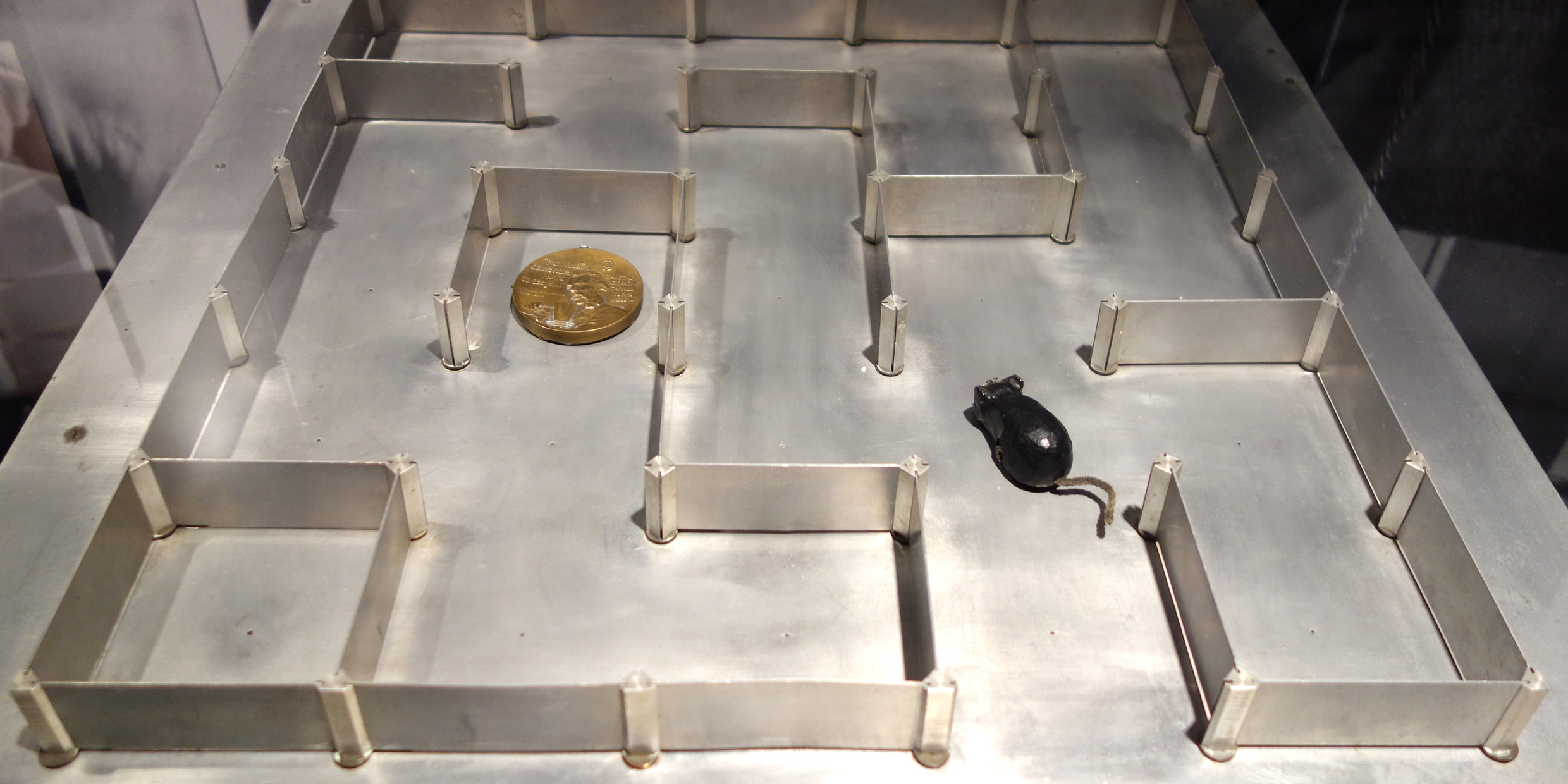

Told about these experiments and speculations, one of my students said: “All rats can do is run through mazes and find cheese. Who wants a computer that finds cheese?”

Another quipped: “We’ll keep the circuits alive by slipping Kraft singles into the floppy disk drive.”

As we discussed a neurochip future, other wacky scenarios passed through our minds.

Will hybrid computers made of living brains cells be absent-minded? (“Now where did I store that payroll data.”)

Will neurochips age, with consequent loss of memory? (“I remember the graphic, but I forget the filename.”)

Will rat-brain computers resent being controlled by a “mouse?”

Will they multiply like rats?

Will Bill Gates chase ratware off the market by introducing a line of machines incorporating cat brain cells?

Or will the Microsoft catware machines tend to laze about in the sun and stubbornly refuse to follow instructions?

And what about the possibility of a more literal kind of computer virus, something similar to the rat-borne bacilli that caused the Black Death?

If neurochips are best suited for computers with single, dedicated tasks, then the cells used on the chips should be chosen to take advantage of evolutionary refinement for each specific task.

For example, dog brain cells might be most effectively used in chips for robots that fetch slippers. Unfortunately, the same robots might chew up the morning paper.

Human brain cells would clearly be best for chess-playing neurocomputers, although the machines might be inclined to throw tantrums and stomp off the stage when defeated by more conventional all-silicon machines.

One thing is certain: As we enter the next century, the distinction between living and non-living will become increasingly blurred. The response of my students to the ratware experiments is encouraging; we will need all the humor we can get if we are to live in harmony with hybrid computers that need to be both plugged in and fed.