Originally published 11 July 2004

A grandchild’s crayon drawing decorates our fridge. A big round Sun with a smiley face.

Why do very young kids always put a face on the Sun?

The Swiss child psychologist Jean Piaget gave us the answer.

During the mid-twentieth century, Piaget published a number of influential books on the inner lives of children. A child’s earliest understanding of the world is invariably animistic (everything is alive) and artificialist (everything is the result of a conscious agency), he said. Very young children truly imagine that the Sun is alive. Ask a child why the Sun is in the sky and the answer will be some version of “It was put there for me.”

Children confuse internal and external worlds, the psychical and the physical. Only with time do they recognize the external and independent reality of Sun, Moon, wind, clouds, trees, stars.

Piaget believed these stages of development in children are universal and innate.

Anthropologists tell us that animistic and artificialist thinking is universal among all pre-scientific peoples of the world. The parallel between the intellectual development of children and the evolution of science was not lost on Piaget.

Both as individuals and as a species, we begin with projections of our inner lives onto the world, and move towards recognition of an external reality that is independent of ourselves.

It has become fashionable of late among certain academics to suggest that animistic and artificialist views of the world — such as those of children or pre-scientific cultures — are no less legitimate than the worldview of science.

There is no knowledge that is independent of the knower, say these postmodern relativists, and scientific knowledge has no more claim to objectivity than any other kind of knowledge.

But if we have learned anything during the last few thousands years of human development it is that animism and artificialism lead nowhere. Scientific thinking has been the only effective engine of material progress.

Science makes three assumptions about the world:

- There is a reality that exists independently of our own minds.

- Things happen according to natural laws, not at the whim of a conscious agency.

- Nature’s laws can be known with an ever greater degree of confidence.

That’s it. And that’s why science works and magic doesn’t.

The Indian philosopher Meera Nanda puts it this way: “While all medieval, pre-Galilean sciences, whether from Europe, Asia or Africa explained nature through anthropomorphic metaphors peculiar to their time and place, modern science alone managed to break free of time and space.”

Modern science is the sea into which all the rivers of local understanding flow, says Nanda, and which brings new ideas and innovations from around the world to all shores alike.

Jean Piaget understood this too. He was a child prodigy who became interested in science at an early age. He wrote and published his first scientific paper at the age of ten, a short note on sighting an albino sparrow. He honed his observational skills with studies of the mollusks of Lake Geneva, and earned a Ph.D. in zoology.

Eventually he turned to the study of the inner life of children precisely to gain a deeper understanding of the scientific quest for reliable knowledge of the world.

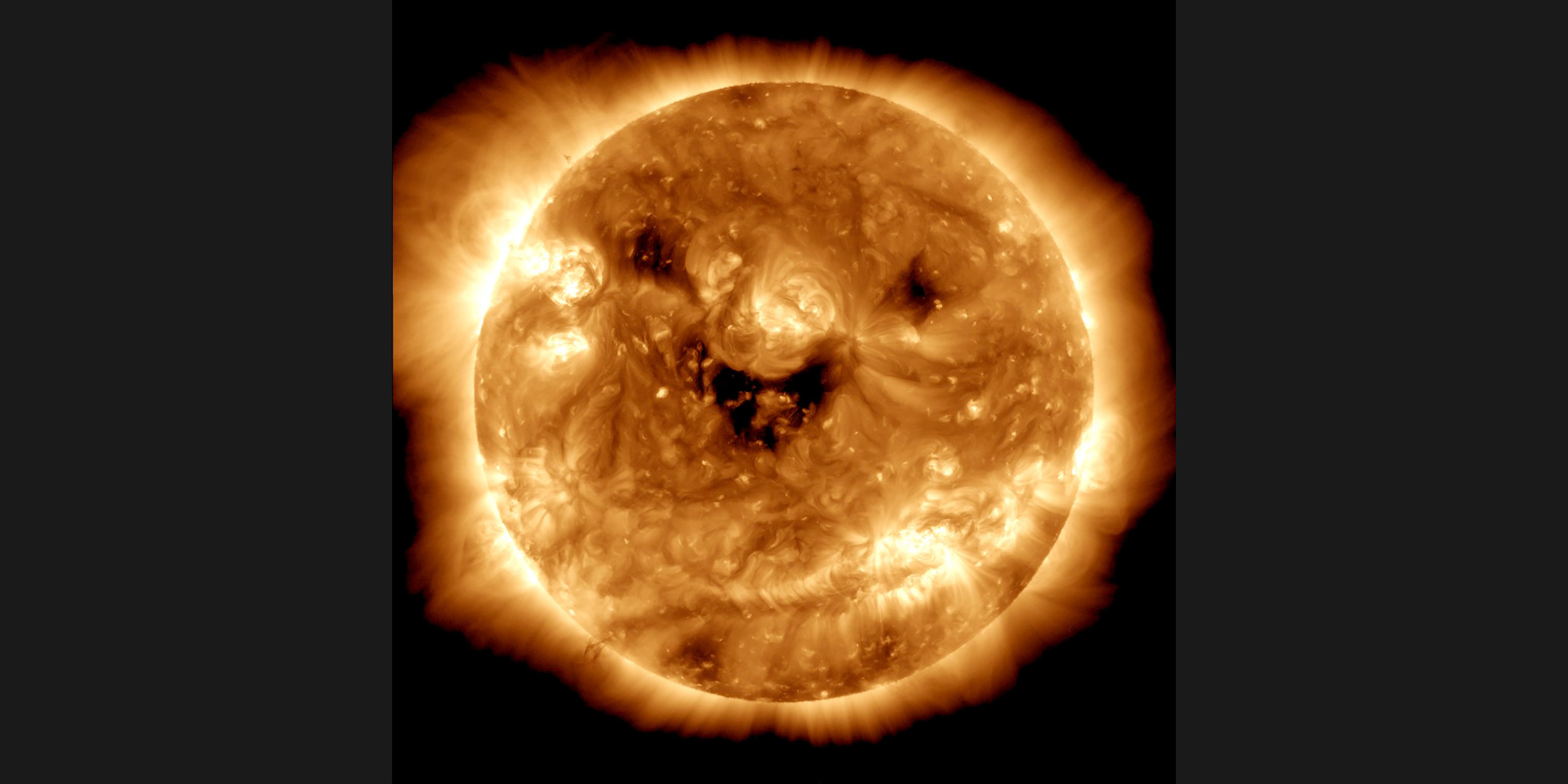

A child puts a smiley face on the Sun because it is reassuring to imagine a friendly Sun who follows her about the yard. It requires rather more daring to accept a Sun that is a vast, distant sphere of fire, inanimate and indifferent.

The Sun we study with satellite telescopes is a far cry from the humanlike Sun god of the ancient Egyptians or the Greek Helios who drives his golden chariot daily across the sky.

Or the smiling orb of the child.

Knowledge is not all relative. Some knowledge is more reliable than others. To accept that fact is called growing up.