Originally published 3 June 2003

Every now and then astronomers come up with a photograph that deserves wider circulation than it gets in the science journals.

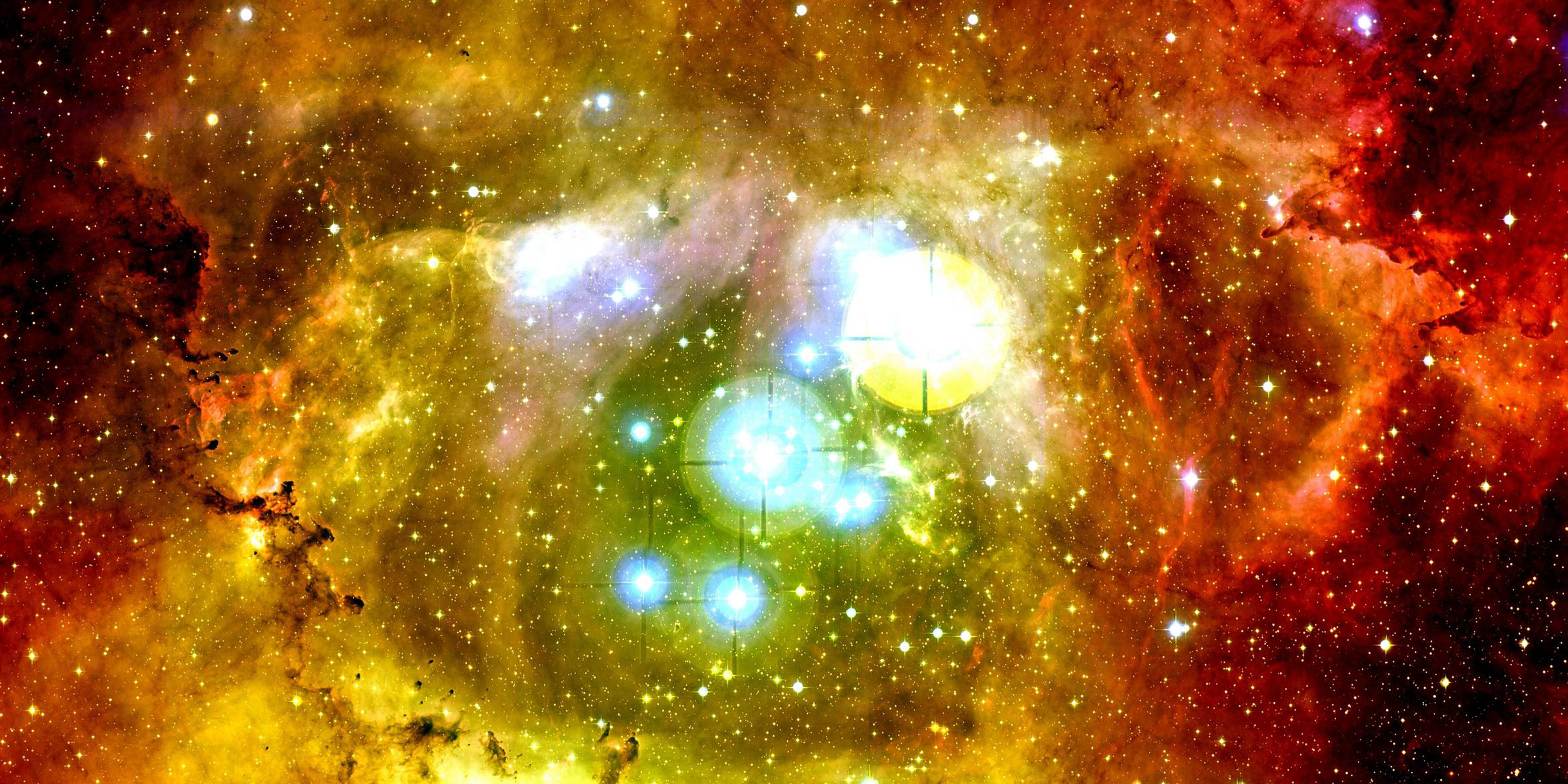

A few months ago, I shared in this space a spectacular image of the Eagle Nebula made at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona. This time it’s the Rosette Nebula, photographed with a new digital camera — the world’s largest — at the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii.

The photograph is reproduced on this page, but you will want to view it on the Internet, at cfht.hawaii.edu/News/MegaPrime/. If you don’t have access to a computer and the Internet, go knock on your neighbors’ door. They should see the picture, too.

The Rosette is a huge cloud of glowing gas and dust heated to luminescence by hot stars recently born out of the material of the cloud. The newborn stars blaze at the center of the nebula, and their radiation has blown away the gas around them, hollowing out the center of the cloud.

Ionized hydrogen gas glows red. Ionized oxygen glows green. The dark knots and streamers in the nebula are dense accumulations of gas, perhaps soon to turn on as new stars when gravity compresses them further.

The nebula is a nest of hatchling stars — stars of all sizes, stars with planets. Our own sun may have been born in a cloud such as this 5 billion years ago. If so, we have long since flown the nest.

The Rosette lies about 5,000 light-years from the Earth, in an outer spiral arm of our Milky Way galaxy. It is about 65,000 times the diameter of our solar system.

Even at its great distance from the Earth, the nebula fills a part of our sky twice the diameter of the full moon. And yet nothing in the photograph is visible to the unaided eye. Go out on a dark winter night and look toward the Rosette — to the left of Orion’s shoulder — and you’ll see only black sky.

And that, it seems to me, is the most wonderful thing of all.

That such unseen wonders exist all around us.

This new photograph of the Rosette Nebula shows what would be visible to our eyes if our eyes were the size of swimming pools and sensitive to almost all of the incident light.

But, of course, our pupils are only a few millimeters wide, and our retinas are sensitive to only a few percent of the light that falls upon them.

Our biology limits our perception to a tiny part of reality. But our cunning transcends our senses. Evolution gave us an abundant tangle of neurons at the top of our spines, and we have used that intelligence to design artificial eyes.

The camera that photographed the Rosette has 340 megapixels, compared to the four or five megapixels in the best commercial digital cameras. Three exposures were made, with blue, green, and red filters, then combined with a computer to give something resembling what we might see with our eyes — again if our eyes were the size of swimming pools.

And so we have entered the universe of the nebulas, but we don’t quite know what to make of it. Many of us recoil from the yawning galactic spaces, the myriad of worlds, preferring the tidy cosmic egg of our ancestors, bounded just up there with a shell of stars and centered comfortably on ourselves. We are reluctant to surrender our sense of self-importance, our age-old conviction that we are the reason for it all.

But maybe in some emergent sense we are the reason for it all. With the evolution of the human mind, the universe of the nebulas and the galaxies has become conscious of itself. We may not be the most intelligent creatures among the stars, but we are certainly the brightest creatures we know about.

Bright enough to make the dark night bloom with roses.