Originally published 15 November 1993

I sing of slime electric.

The armies of those I love engirth me and I engirth them, they will not let me off till I respond to them, and discorrupt them, and charge them full with the charge of the soul.

OK, I’m borrowing from Walt Whitman. These slightly modified lines of his famous poem “I Sing the Body Electric” are perfect for introducing my paean to slime molds.

A paean? A song of praise? You bet. Slime molds are undeservedly corrupted by their name. Doubly corrupted.

But wait. Watch. Observe their streamings and slitherings and towerings. They are a mass of individuals. They are a society. They blossom like flora. They creep about like fauna. They are plant and animal. And neither. They embody in their life cycle the history of life, and the history of our race. They are charged full with animation.

For years, I have been fascinated by microphotographs of slime molds in scientific books and articles. Recently, I acquired my own colony of Dictyostelium discoideum, the researcher’s favorite slime mold. I observed their life cycle with a microscope.

With Whitmanesque gush, I sing their praises.

At first they are invisible, an uncountable army of free-roaming amoebas, single-celled organisms, grazing on bacteria.

They multiply by fissioning, splitting down the middle, two from one. Again. And again. Their population soars. Their food becomes scarce.

Triggered by hunger, some among them secrete a chemical called acrasin, after Acrasia, the cruel witch in Spenser’s The Faerie Queene who attracted men and turned them into beasts. It is a call. A signal. The amoebas gather in the tens of thousands, streaming in gleaming rivers to the assembly point, becoming visible in their slimy congregations.

Surrendering their individuality, they heap themselves into a gooey blob half-a-millimeter high. The blob falls onto its side, becoming a slug-like creature. Some amoebas know they are anterior; others resigns themselves to bring up the rear. The front end of the slug lifts as if to sniff the wind. The creature slithers on a film of slime toward light and warmth.

As it slithers, the cells begin to change. The anterior cells are destined to become a stalk; the posterior cells will become spores.

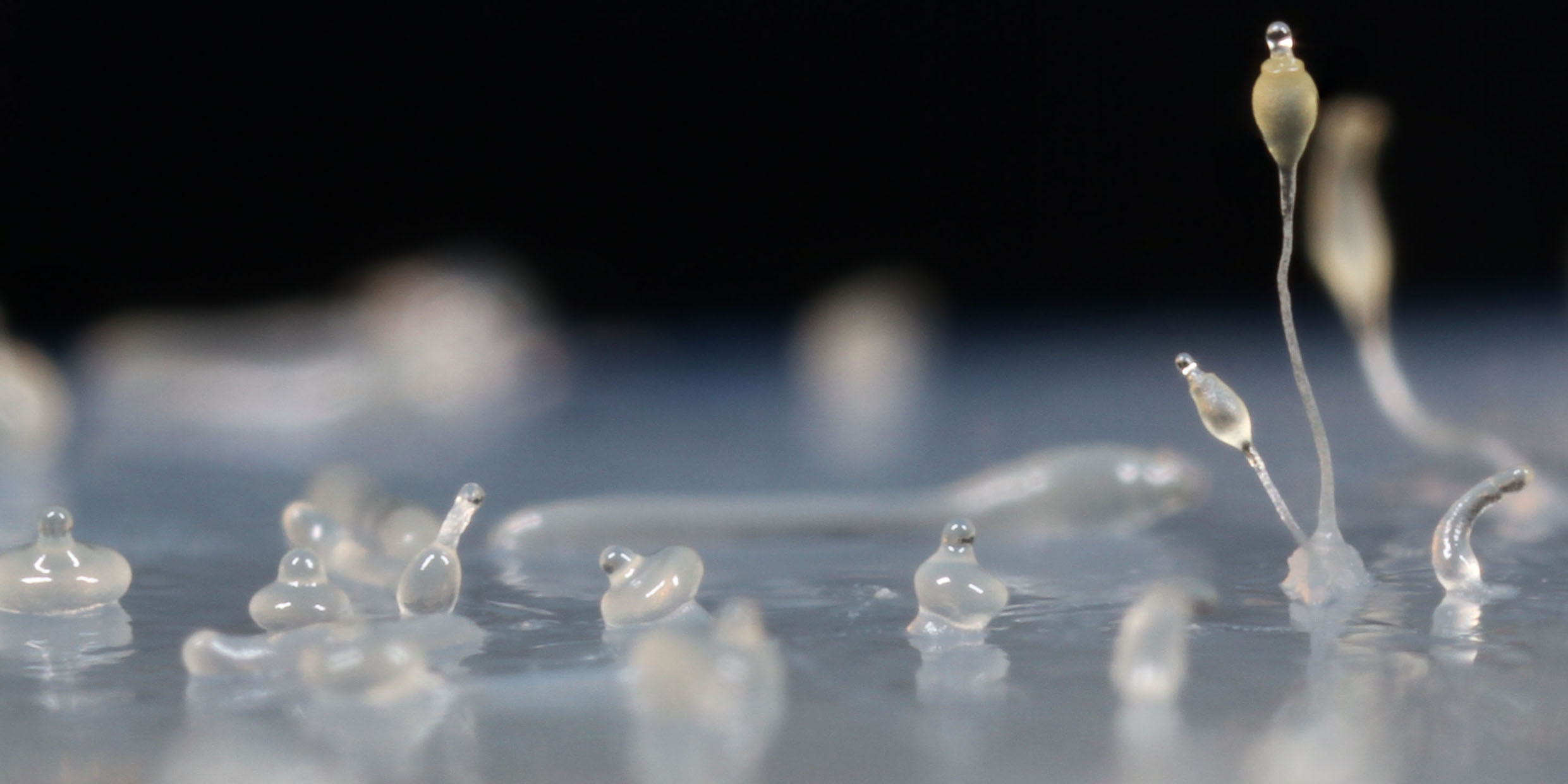

A bright, warm place is found. The slithering ceases. Anterior cells push down through the spore mass, becoming a slender pillar anchored at the base, lifting a perfect sphere of spores into the air. Sometimes several spheres are strung along a single stalk, like tiny raindrops on a spider’s thread. The spores are dormant amoebas that will travel on the air when the sphere bursts asunder to form new colonies. The stalk amoebas will die; they have sacrificed themselves that others might live.

The fruiting tower is beautiful. Glittering. Translucent. An Ozmian minaret, sometimes as tall as this letter i. Fifty thousand amoebas pool their individual resources to build a reproductive spire.

What is this thing? Is it a plant? An animal? A fungus? Are the slug and the tower congregations of one-celled organisms that have temporarily surrendered their independence, or are they a multicelled organism whose reproductive spores only temporarily live on their own?

These questions have long exercised biologists. It is now widely agreed that slime molds are neither plant nor animal nor fungus but members of the kingdom Protoctista, which encompasses some of the most ancient single-celled organisms. Yet slime molds have characteristics of plants, animals, and fungi. In their delightful inclusiveness, they are a precis of all life on Earth.

They even reproduce on a micro-scale the social history of humankind: nomad hunters and gatherers banding together to build cities and raise towers, specializing for different occupations.

More fundamentally, in their curious life cycle slime molds recapitulate that episode in the history of life, which occurred about 700 million years ago, when single-celled microorganisms, having lived on their own for 3 billion years, came together to form multicellular organisms. Invisible life became gloriously visible, and wonderfully diverse. Creatures individually smaller than the point of a pin piled themselves together to become, in the fullness of time, brontosauruses and blue whales.

There is a sense, I suppose, in which you and I are slime molds of a sort, accretions of billions of cells that have banded together and specialized for the purpose of producing sperms and ova. The essence of life is to make more life. Over an over again in the history of life the efficiency of reproduction has been aided by collaboration, symbiosis, even altruism.

The stalk cells of a slime mold do not know that they are sacrificing their own lives to lift their spore cousins so that they might be more efficiently dispersed, no more than the hundreds of types of specialized cells in our own bodies know that their collective evolutionary purpose is to produce a few successful sperms or ova. But they do it. Is it altruism? Call it life. A great driving energy implicit in matter itself, the green fuse, the compulsive inevitability of animation.

A gooey colony of Dictyostelium discoideum has performed its marvelous transformation on the stage of my microscope. I admire them, engirth them, and discorrupt them. Whitman-like, I sing their praises. They are charged full with the charge of the soul.