Originally published 13 January 1986

I sing the praises of Escherichia coli, bean-shaped bacterium, inhabitant of the human intestine, best understood (as I shall soon reveal) of all God’s creatures.

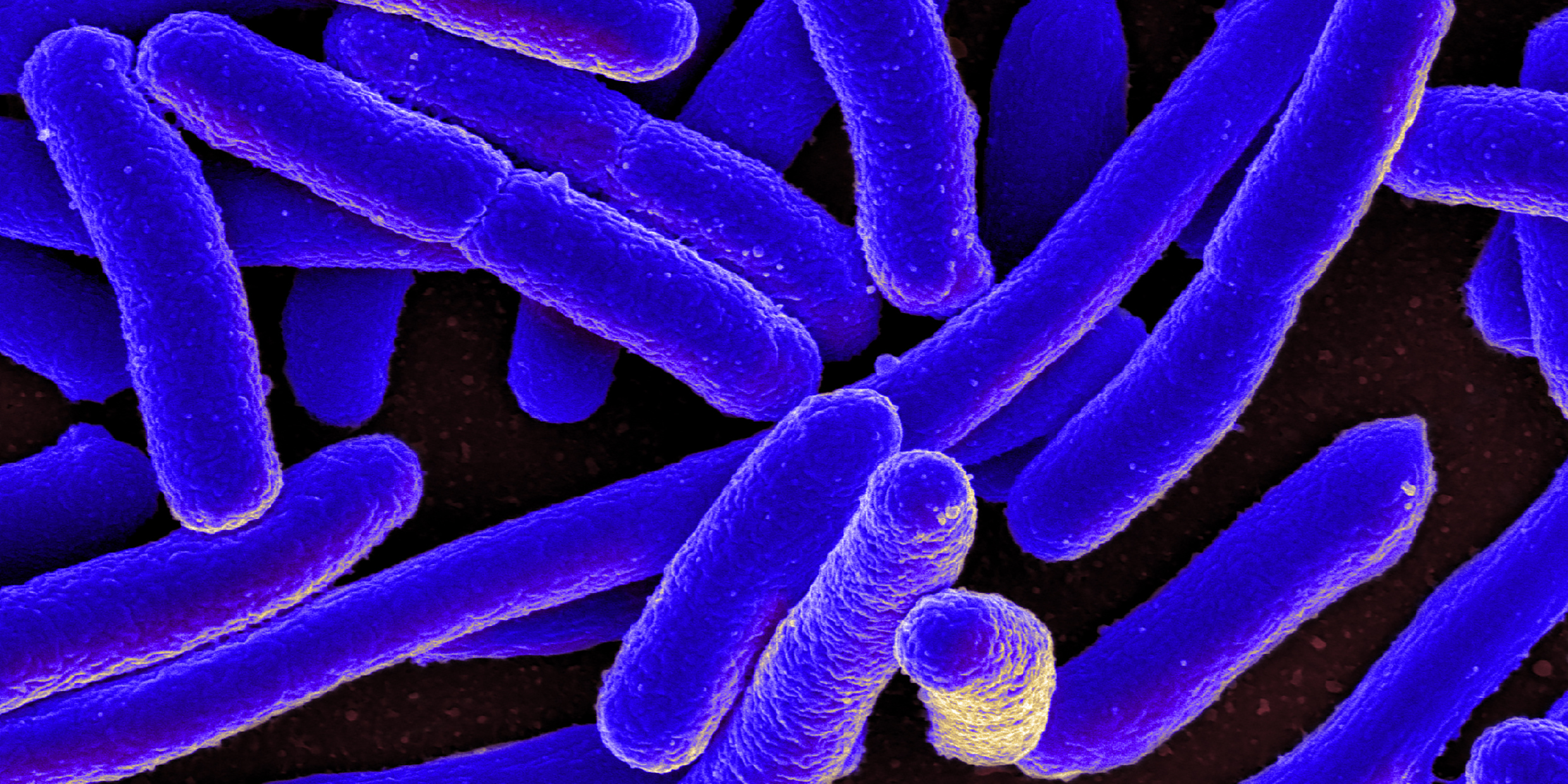

Bacteria are the most primitive forms of life on earth. E. coli is about as simple as a creature can be and still be alive. It is a pinch of protoplasm in a membrane. It has a single chromosome and a loop of DNA about as big as the dot on this letter i. By contrast, the DNA in a human cell is a thousand times as long.

But E. coli moves. It feeds. It reproduces. It recognizes and communicates with its own kind. In a primitive sense, it can even remember. It gets from here to there by wriggling its whiplike appendages; or screwing them, actually, like propellers. It has, such as it is, a life of its own.

E. coli is microscopic. A million of them laid end to end would make a line only as long as my arm. But there are enough of the bacteria inside of me now to form a line that would stretch from Boston to San Francisco. A significant part of my body weight is not me at all, but my burgeoning population of E. coli.

Ever the dinner guest

As house guests go, my E. coli are not unwelcome. They produce, I am told, certain useful vitamins. They sometimes devour other micro-organisms that cause disease. But mostly they just go about their business, happily sharing my space, doing me very little good or harm. The technical term for our relationship is commensal: literally, “eating at the same table.”

E. coli is the most intensively studied of any living organism. I checked a recent volume of Biological Abstracts, a journal that indexes biological research. There were five times more references to E. coli than to any other species. This little bacteria has no secrets. Its genes have been exhaustively mapped. Its proteins have been cataloged. It has been poked and probed in a thousand ways.

It is the simplicity of E. coli that makes it so attractive to science. It has become the white rat of microbial research. It is hardy. It multiplies itself every twenty minutes. Genetic researchers, especially, have found E. coli to be the ideal subject. It is possible to snip little bits of gene from other creatures and splice them into the DNA of E. coli, thus tricking the bacteria into doing things it would otherwise know nothing about. This new technique is called recombinant DNA research.

E. coli’s genes have been engineered in ways to cause the creature to unwittingly manufacture insulin, interferon, and human hormones, immensely valuable substances that are otherwise extremely difficult to obtain. The human brain hormone somatostatin is a substance that inhibits the secretion of the pituitary growth hormone. The researchers who first isolated somatostatin needed a half-million sheep brains to collect 5 milligrams of the substance. A two-gallon culture of E. coli can quickly produce the same amount.

The dark side

The future of recombinant DNA research holds the promise of engineered cures for such genetic diseases as hemophilia and diabetes.

But there is a dark side to restructuring genes. In the early days of genetic research it was feared that a dangerous variant of re-engineered E. coli might escape from the lab and cause disease among humans. Stringent measures were taken to insure the containment of the bacteria. Nowadays, most E. coli research employs a deliberately crippled strain of the bacteria that cannot live except in the specific conditions of the lab.

With the success of these genetic engineering experiments, a new industry was born. It will not be long before there are factories in which vast numbers of genetically altered E. coli labor like Perdue chickens to produce useful products for mankind: medicines, insecticides, fertilizers, and — if we are not watchful — weapons.

This new power to tinker with the code of life raises staggering ethical dilemmas. Like all technologies, recombinant DNA research carries the power for both good and evil. And I can’t help but feel a bacterium-sized twinge of conscience about the cavalier way we manipulate E. coli’s genes. On the other hand, bacteria have survived assorted terrestrial and cosmic calamities for more than three billion years; they will undoubtedly still be here when we are gone.

I sing the praises of Escherichia coli, best understood of my fellow creatures, industrious bacterium, hardy survivor, commensal friend.