Originally published 9 November 1987

The British physicist and philosopher of science John Ziman recently published a book called Knowing Everything About Nothing: Specialization and Change in Scientific Careers. This column is not about the book. It is about the title of the book.

Ziman takes his title from the old joke about the difference between philosophers and scientists: Philosophers learn less and less about more and more until they know nothing about everything. Scientists learn more and more about less and less until they know everything about nothing.

Specialization is endemic in science. More and more people are spending more and more time learning more and more about ever smaller details of the world. Research in science expands like the root system of a tree, dividing itself again and again, probing with ever finer rootlets and tendrils into the remotest corners of nature.

Take a glance at the titles of typical reports in any issue of Science, the weekly journal of the American Academy for the Advancement of Science. Here are a few from [the 16 October 1987] issue: “Downregulation of L3T4+ Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes by Interleukin‑2″; “Heritability at the Species level: Analysis of Geographic Ranges of Cretaceous Mollusks”; “Phylogenetic Relations of Humans and African Apes from DNA Sequences in the psi eta-Globin Region.”

This is not a journal for specialists. The editors of Science go out of their way to give an account in understandable English of what they judge to be the most significant reports in each issue, and they do a good job of it. Still, one cannot help but feel that science speaks more languages than there are ordinary human tongues, and that a scientist in one discipline is cut off by the curse of Babel from what goes on in disciplines other than his own.

Some good things are happening

And there are good things going on, right across the board, from the immunologists who study lymphocytes to the paleobiologists who excavate Cretaceous mollusks. Consider, for example, the last of the three articles listed above. The title is a jaw-breaker. Even the abstract of the article seems to have been written in a foreign language. But what the article describes is of general interest: A comparison of certain segments of the genetic code of chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, and humans suggests that humans and chimpanzees are more closely related than either is to the gorilla. Chimps and humans may be closest cousins.

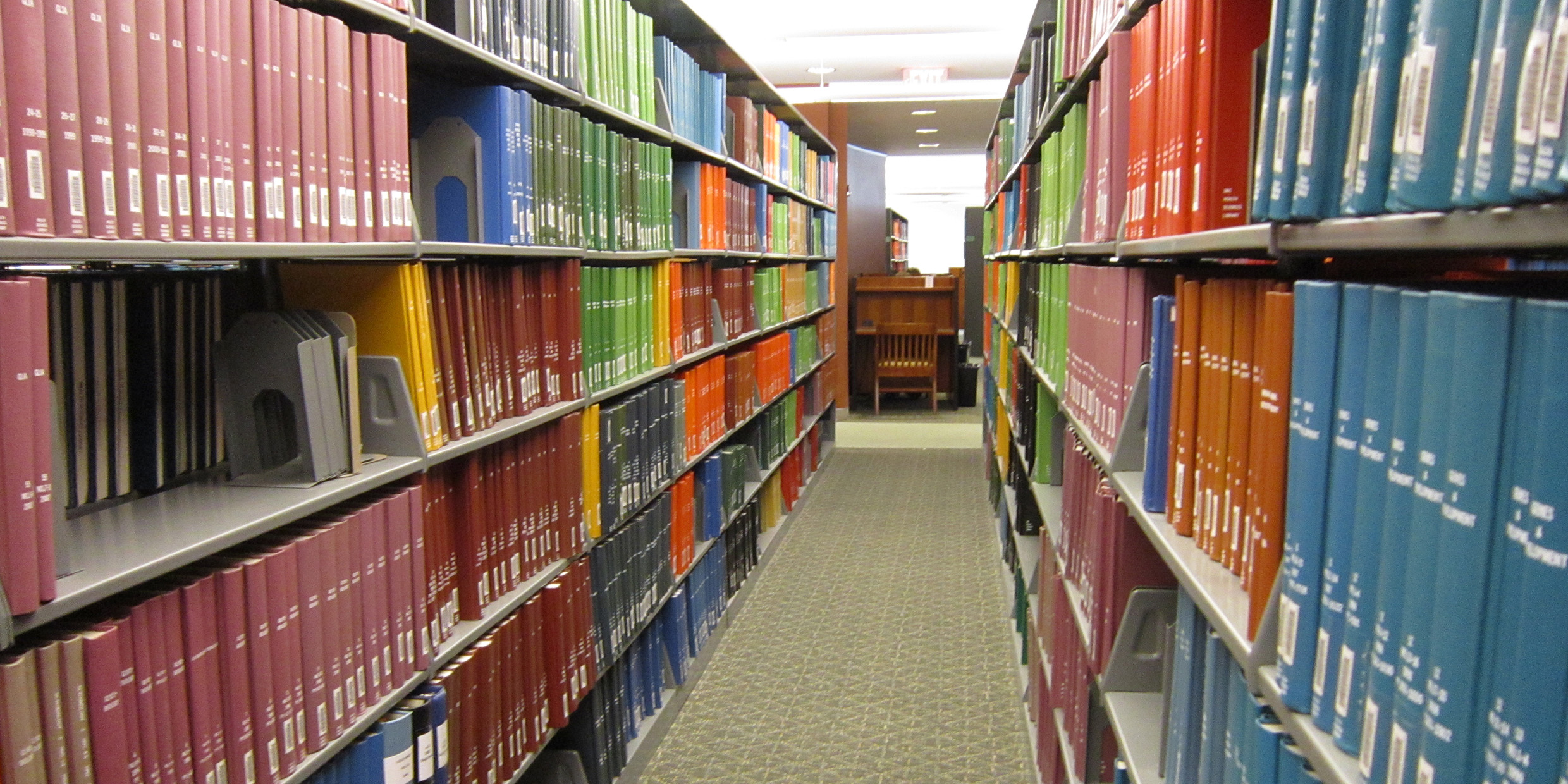

If non-specialist journals, such as Science, are so dense with special lingos, then what can be said of the huge number of journals devoted to particular disciplines — or to subsets of subsets of particular disciplines?

Ulrich’s International Periodicals Directory lists more than 1500 periodicals under the heading of biology alone. Each year the British journal Nature reviews new science periodicals. This year’s crop included the American Journal of Physiologic Imaging, Journal of Enzyme Inhibition, Journal of the North American Benthological Society, Microbial Pathogenesis, Transport in Porous Media, and Yeast. Among journals submitted to Nature but not reviewed were Applied Clay Science, and Dysphagia: An International Journal Devoted to Swallowing and Its Disorders.

Apparently scientists will pay through the nose for the privilege of knowing more and more about less and less. A subscription to eight issues of Bone and Mineral costs $306. A year of Liquid Crystals (a monthly) costs $490. What is the minimum readership necessary to make a new journal a commercially successful proposition? Presumably, if all of the authors who publish in the journal also subscribe to it, regardless of its price, the journal is deemed a success.

The question is what to do

It is easy to decry the tendency toward specialization in science, but hard to know what should be done about it. Specialization has proved to be an effective way to gain knowledge. Scientific knowledge grows faster than our ability to assimilate much of what is learned. It is difficult for an individual to be master of more than one little tendril of the huge root system of science.

Educators should be careful that young scientists not begin to specialize too early, at least not until they have learned to appreciate the majestic common themes that run throughout all of science. And we should value people like Stephen Jay Gould and Philip Morrison, those rare scientists who are masters of a particular discipline and also persuasive generalists who help us recognize the common themes.

But alas, for the most part, we find ourselves on the horns of a dilemma, philosophers on one horn, scientists on the other. Here’s an article from the current issue of Review of Metaphysics: “Is Each Thing the Same as Its Essence?” That’s called knowing nothing about everything.

And here’s an article from the current Chemical Reviews: “Acetylcholinesterase: Enzyme Structure, Reaction Dynamics, and Virtual Transition States.” That’s called knowing everything about nothing.

Both approaches leave something to be desired. It is in the gap between the horns that we live our lives.