Originally published 22 February 1988

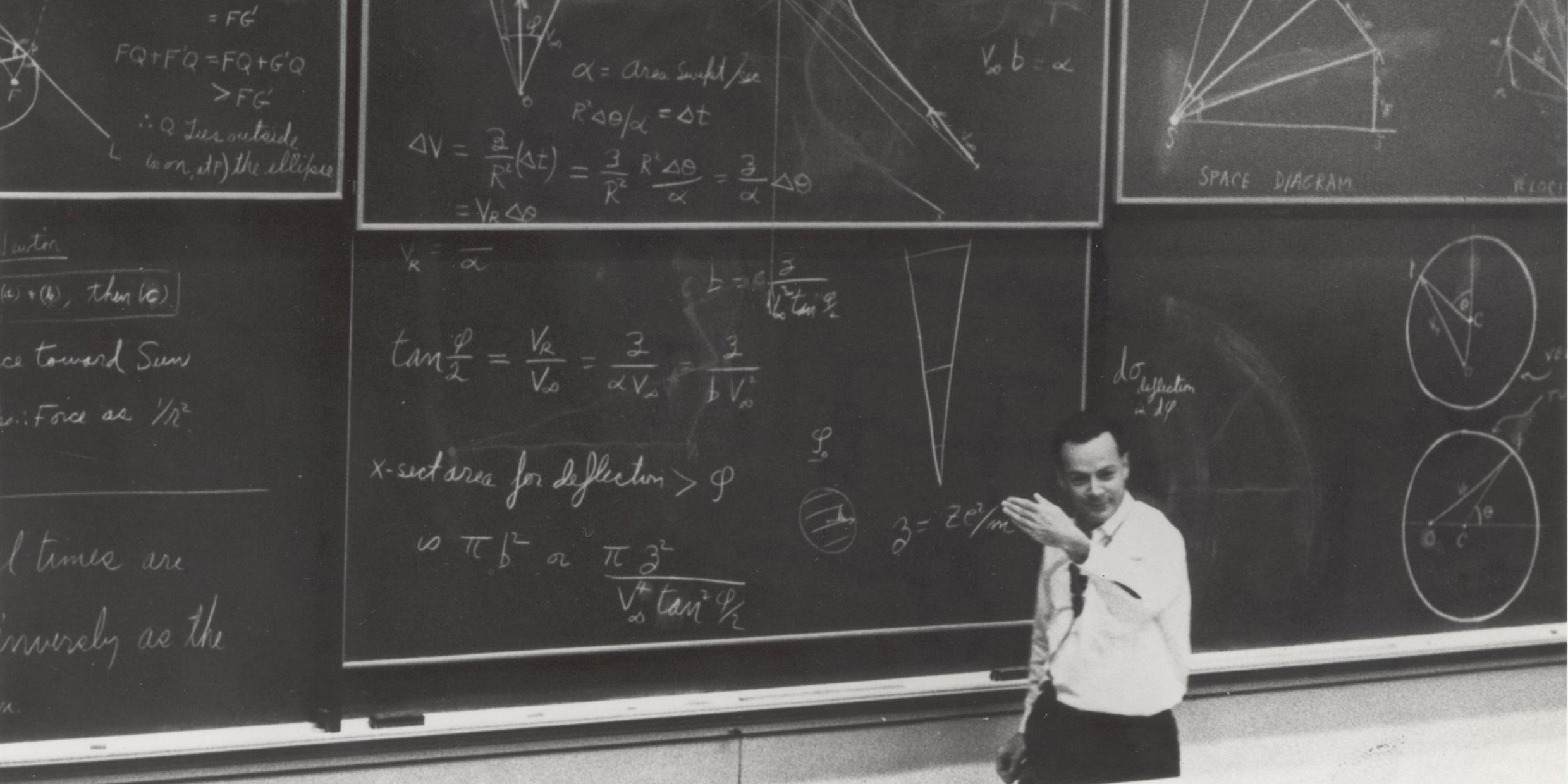

Thirty years ago when I was a graduate student in physics at UCLA I used to occasionally go over to Caltech to hear Richard Feynman lecture on physics. Feynman, who died this past week [in 1988] at age 69, was famous even then, although his Nobel Prize was still a few years in the future. He was also a very funny man. He could be talking about quantum mechanics and have his audience in stitches. He was a first-rate stand-up comic, and I always went away thinking that science was both fun and funny.

I still think science is fun, but I don’t often think it’s funny. Feynman stands out in my memory because his kind of humor seems rare in science. When I saw that a session of the recent American Association for the Advancement of Science convention was titled “Science and Humor,” I decided to check it out — to find out if I was missing something.

Almost nothing, it turns out. It was the unfunniest two-and-a-half hours I ever spent in my life. No, I take that back. The first speaker at the seminar was Sidney Harris, a cartoonist whose work has appeared in American Scientist, Science, and other publications. Harris was funny. But Harris isn’t a scientist. He doesn’t even know many scientists.

As for the rest of the speakers, all scientists — well, like I said, Feynman stands out in my experience because he was virtually unique.

I should have known what I was in for when I read the program description. Excerpts: “The symposium will examine how anecdotes, jokes, and cartoons about science have come into being, and what can be learned from them about the culture of science and also about the larger culture in which science is practiced… The specific character of the humor associated with some specific fields will be detailed… The intrinsic relationship between theory and wit will be examined and analyzed.”

That description tells more about humor in science than did any of the speakers. Namely, forget it. Any symposium on humor that announces itself with such leaden jargon is doomed from the start.

OK, so why is there so little humor in science? At the risk of launching still more lead balloons, I herewith offer several theories.

1) Scientists take themselves too seriously. As a case in point, consider one more sentence from the symposium description: “The symposium will look into how humor has developed in coping with stressful situations in the practice of science, and humor relating to women in science will be presented and analyzed.”

2) Scientists don’t take themselves seriously enough. At the symposium we saw scientists dressing up in funny shirts to enliven lectures, and singing songs like “Let’s not clap for Gonococcus.” Gonococcus, by the way, is the bacterial agent for a certain genital infection. Which brings us to Theory 3.

3) Scientists spend too much time poring over petri dishes. A large part of the “humor” at the symposium was either sexist or schoolboy sexual. One speaker offered as an example of humor in science illustrations from an essay, “A stress analysis of a strapless evening gown,” that I seemed to remember reading as an undergraduate, and for all I know was around in my father’s day. It suggests that humor in science may suffer from a case of arrested development.

4) Scientists spend too much time in monovariate relationships. Success in the lab usually means reducing the variables in an experiment to only one. A good joke works by bringing together two wildly disparate variables. Cartoonist Sidney Harris got the best laughs at the symposium by putting a spin on science and baseball (a tight cluster of men in spacesuits playing “High-gravity baseball”), science and decorating (“We did the whole room over in fractals.”), and science and consumerism (“Great Moments in Shopping: Louis Pasteur buying his first quart of pasteurized milk.”).

5) Brevity is the soul of wit and scientists don’t know when to stop talking. A few weeks ago retired schoolteacher Ben Stewart offered here in Sci-Tech a collection of kids’ statements on science that were funnier than anything I heard at the symposium (“Hard mud is called shale. Soft mud is called gooey.”). Stewart quoted Mark Twain’s contention that the “most interesting information comes from children, for they tell all they know and then stop.” Scientists tell all they know and then organize symposiums so they can tell it all again. And again.

Science is a huge community of very bright people doing complex and wonderful things that offer ample opportunities for humor. The scarcity of good science wit is little short of astonishing. And please don’t refer me to The Journal of Irreproducible Results, a science parody published five times a year that seldom rises above the merely silly.

One last theory:

6) Funny people don’t become scientists, they become cartoonists. Sidney Harris got a small laugh with a cartoon that was just a picture of a dot, captioned: “The universe before the Big Bang (actual size).” He got a bigger laugh as he mused about the size of the dot as projected on the big screen at the front of the meeting room. “It was smaller on the paper,” he said wistfully.

And then he added: “It doesn’t matter. It was only a guess.”