Originally published 17 June 2007

John Holstead is a Yorkshireman by birth, a West Kerryman by adoption. He has had a checkered career: marine engineer, carpenter, sculptor. It is as an artist that I have know him best for thirty years. Two of his beautiful sculptures of polished wood grace our cottage.

John has long been interested in science. His bookshelves, I have noticed, are dense with works of popular science. And it is from science that he took his inspiration for the three large sculptures recently on display in a gallery in Dingle. They are titled collectively Relative To the Observer, and with them John wanted to show the the same piece in three different physical incarnations. He was struck by the realization that, according to Einstein’s theory of relativity, every observer literally sees the world from an individual perspective. Of course, as John points out, at the velocities we experience relative to each other here on Earth the differences are imperceptible, but they are there. Part of our individual uniqueness.

But what form would his sculpture take? The universe itself! Says John: “There was a drawback to having the shape of the universe as a model, but one very big plus. The drawback was that no one knows what the shape of the universe is like. The big plus was that no one knows what the shape of the universe is like.” As the artist, John would give his imagination free reign. “The sculptor is happy with expanding space,” he says. “Making space expand is what he does best. Giving an unseen object the space to reveal itself.”

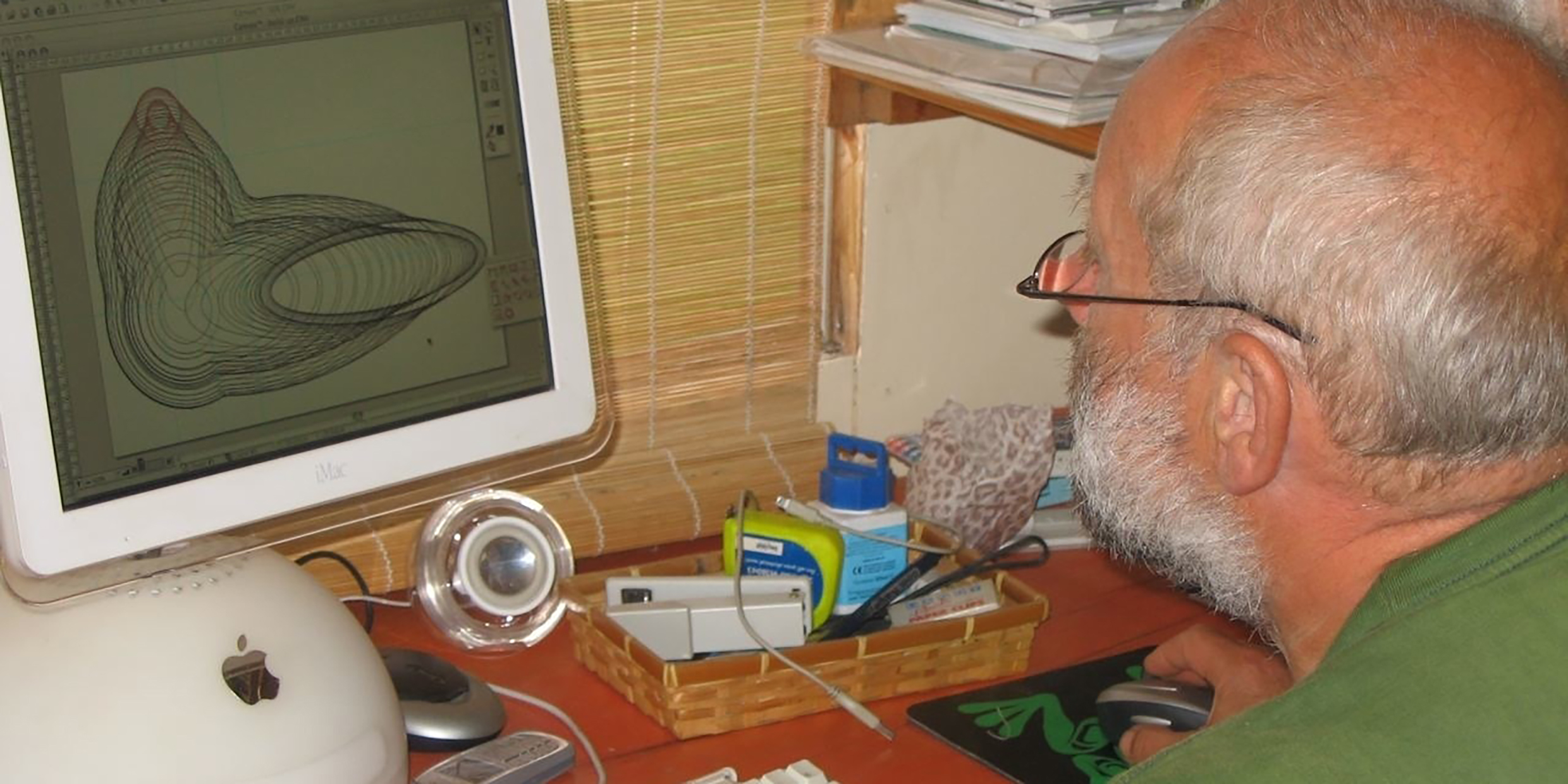

Now the engineer in John took over. For months he worked away at the computer, evolving the shape that embodied his vision of a dynamic, evolving universe. He started with a sphere, and let it flow and grow in ways that only John could explain, with its own built in “laws of nature.” Beautiful computer-generated drawings. Spreadsheets of numbers. He might have been God himself beavering away on the divine Apple Mac in the eons before the Big Bang.

And yes, there would be a part of his universe wrapped in mystery, a deep and beautifully finished interior hidden from the viewer: “You can see into my universe, but no matter how hard you try, there will be some part beyond your knowing.”

The more we learn about the universe, the more questions pop up to be answered, says John. “It is the searching that makes us what we are. It is the searching that is the foundation of all religions, each of which has its own creation story and, if you are good, a happy ending. Neat little packages of answers, gift wrapped in sanctity. Science has no fancy wrapping, but it usually does what it says on the tin, and, if it doesn’t, it is quickly removed from the shelves.”

When at last he was satisfied with his design, the reams of numbers were transferred to marine-grade plywood and dozens of precisely designed pieces were cut out and glued together. As each universe took shape, the inside was carefully smoothed and sanded; there would be no reaching the inner surface once it was all together. Countless hours of shaping and polishing; as John says, “exalting the valleys, making the crooked straight and the rough places plain.” The first of his three universes would be polished wood, “anointed” with oil. “Rubbing in thin coats of wax, I felt like Aladdin,” says John, “waiting for something to leap out of his lamp.”

The out-rushing universe did not stop at hydrogen atoms: “The refining fires of the early stars spawned heavier atoms. These were scattered across the universe in the cataclysmic death of the stars, only to be swept up by cosmic winds and gravity to form new stars. Our solar system, including you and I, is made of such stardust.” John’s second universe is covered with tiny tiles of stainless steel, a glistening homage to hard matter.

His third universe gives expression to the energy that makes up our vision of the universe, “the narrow band of wavelengths between approximately 380 nanometers and 740 nanometers that we call color.” This universe is covered with tiny tiles of Italian colored glass, a rainbow of radiant energy. To look down into the guts of this universe is like looking back to the moment of creation itself.

I wish you could see all of John’s beautiful drawings and the sculptures themselves. They appeal not only to the senses, but to the intellect. John describes the task of extracting information from his drawings and turning it into three-dimensional objects, for him a considerable feat of engineering and art, with hours and hours of sweat. “Our brain does this trick in the blink of an eye,” he notes. “It takes an upside down, two dimensional image, created by photons of light hitting the back of the retina. There a chemical called rhodopsin converts the image into electrical impulses. These are sent up the optic nerve where the brain mentally constructs a three dimensional world, complete with color and perspective. If needs be, the brain will add, sound, smell, texture, taste, and, if you’re lucky, emotion. This miracle happens every time you open your eyes.”

Scientists tell us what there is to see. Artists open our eyes.