Originally published 12 June 1989

Problem: A person wishes to build a square house with an area of 500 square feet. What should be the length of the side of the house?

That’s easy. Get out the calculator. Punch in 500. Push the square-root button. The answer: 22.36067977 feet.

The Calculator Monster has struck again!

Every teacher will recognize the monster’s track. Answers that run to 10 digits, most of them meaningless.

OK kids, put away the calculator. Now figure out the answer? 20 times 20 is 400. Too small. 25 times 25 is 625. Too big. Split the difference. Try 22.5 feet for the side of the house. That’s 506 square feet. Close enough. The person who lives in the house will never know the difference.

Now there’s nothing wrong with calculators. The calculator is probably the greatest boon to quantitative thinking since the invention of Arabic numerals. Every kid should own one and know how to use it.

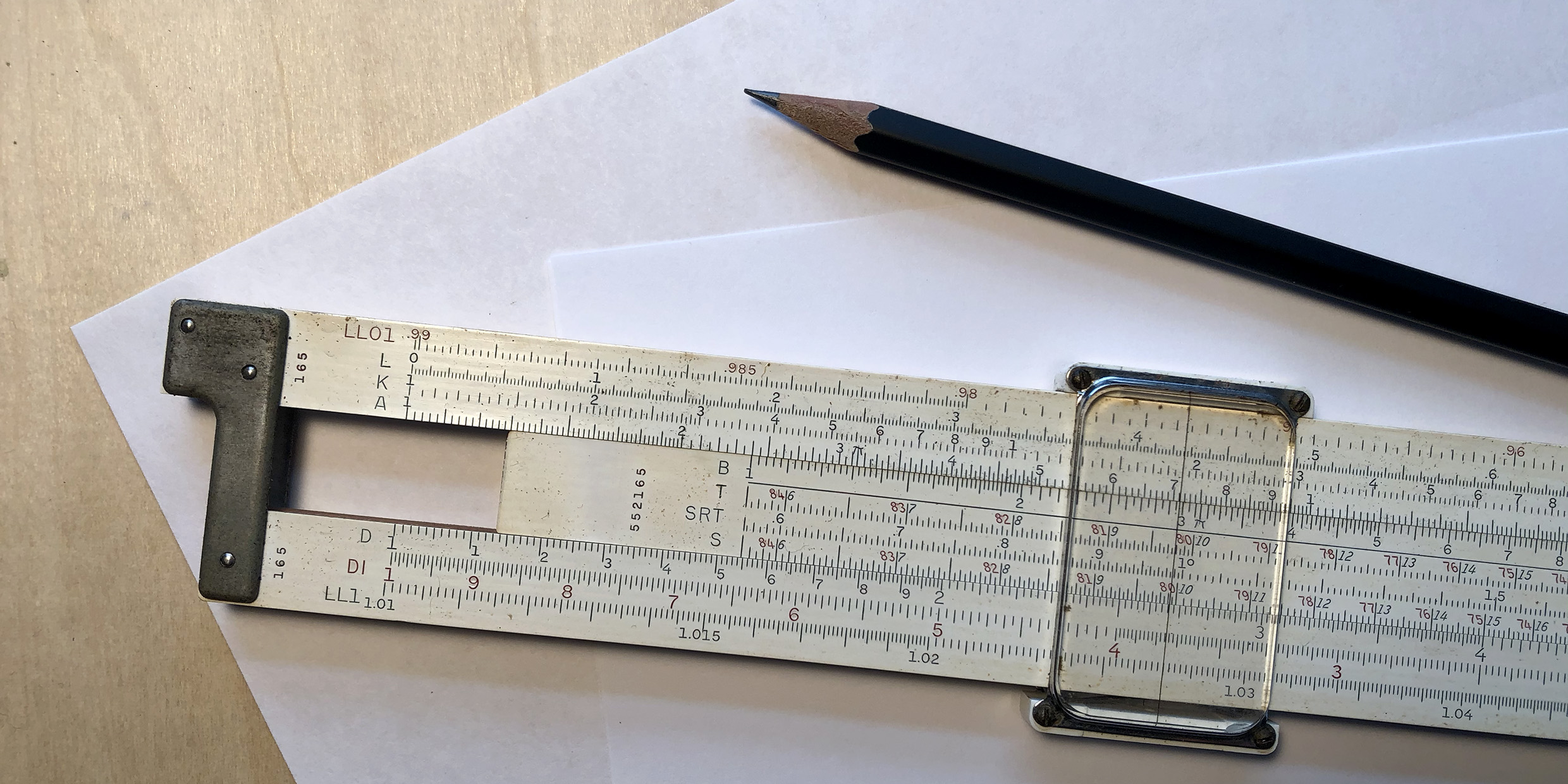

When I went off to college to study engineering my dad gave me his well-worn K+E slide rule. A thing of beauty. A precision instrument. “Wear it with pride,” he might have said. And off we went to class, engineering nerds, slip-sticks dangling at our sides.

If someone had told us then that kids today would carry in the palm of their hand a device costing less than my slide rule that could do arithmetic and a host of higher functions instantly and accurately (to ten significant figures!) we would have said, “impossible.” In those days we were just beginning to use gigantic computers that were barely as powerful as today’s hand-held calculators.

Judicious approximation

But slide rules had one advantage over calculators: They rounded off by necessity. They lent themselves to back-of-the-envelope calculations. They encouraged judicious approximation.

Yes, every kid should own a calculator and know how to use it. But kids should also be taught the art of rounding off. And of making reasonable guesses. Too much precision can sometimes obscure understanding. A lot of good science is done with a vocabulary of “let’s assume,” “more or less,” and “to a first approximation.”

In one episode of Philip Morrison’s television series The Ring of Truth, Morrison makes a clever order-of-magnitude measurement of the size of a molecule by watching oil spread out on a pool of water. One teaspoon of oil poured on water will spread to cover half-an-acre. Assume that the oil slick at maximum extent is one molecule thick; how big is a molecule?

Every high-school student should be able to solve this problem, but, alas, few will have the confidence to try. It helps in solving problems like this to think metrically, and of course the United States is the only country in the world (more or less) that continues to hobble the brain with inches, ounces, teaspoons, and acres.

The first thing an enterprising, metrically-inclined student will want to know is how many cubic centimeters there are in a teaspoon and how many square meters in an acre. So, make reasonable guesses. The side of a sugar cube is about a centimeter; how many crumbled sugar cubes would fill a teaspoon? How big is the lot your house sits on, in acres? An adult’s pace spans about a meter; how many paces to walk the length and breadth of your lot?

What else do we need to know? The formula for the volume of a sphere. Some junior-high geometry. A little quick pencil work on the back of an envelope and—voila!—we have the size of an oil molecule. And not a bad estimate at that.

Now, kids, for a follow up question. Assume that the 240,000 barrels of oil spilled from the Exxon Valdez spreads out into a slick of maximum extent. What is the area of the slick? How many barrels of water are there in the world’s oceans to dilute the oil? Assuming complete mixing, how many Exxon Valdezes would have to empty their contents into the oceans to contaminate the water to one part in a billion with crude oil?

Now for the quiz

There’s no end to the instructive questions students can answer with nothing but reasonable guesses and rough-and-ready calculations. How many trees must be cut down to supply the junk mail that enters American households each year? How large a landfill would be required to receive the junk mail that enters your town in ten years? How long would it take for all the cars and trucks on Earth to cycle the entire atmosphere through their engines? If a warming climate melts the mile-thick ice caps on Greenland and Antarctica, by how much will the level of the the oceans rise?

I would be pleased to hear from high school classes who can provide back-of-the envelope answers to these questions. Don’t look up anything you can reasonably guess, and watch out for those insignificant figures. Calculators (or slide rules) are permitted, but only as a tool. Microchips are no substitute for brains.