Originally published 2 May 1994

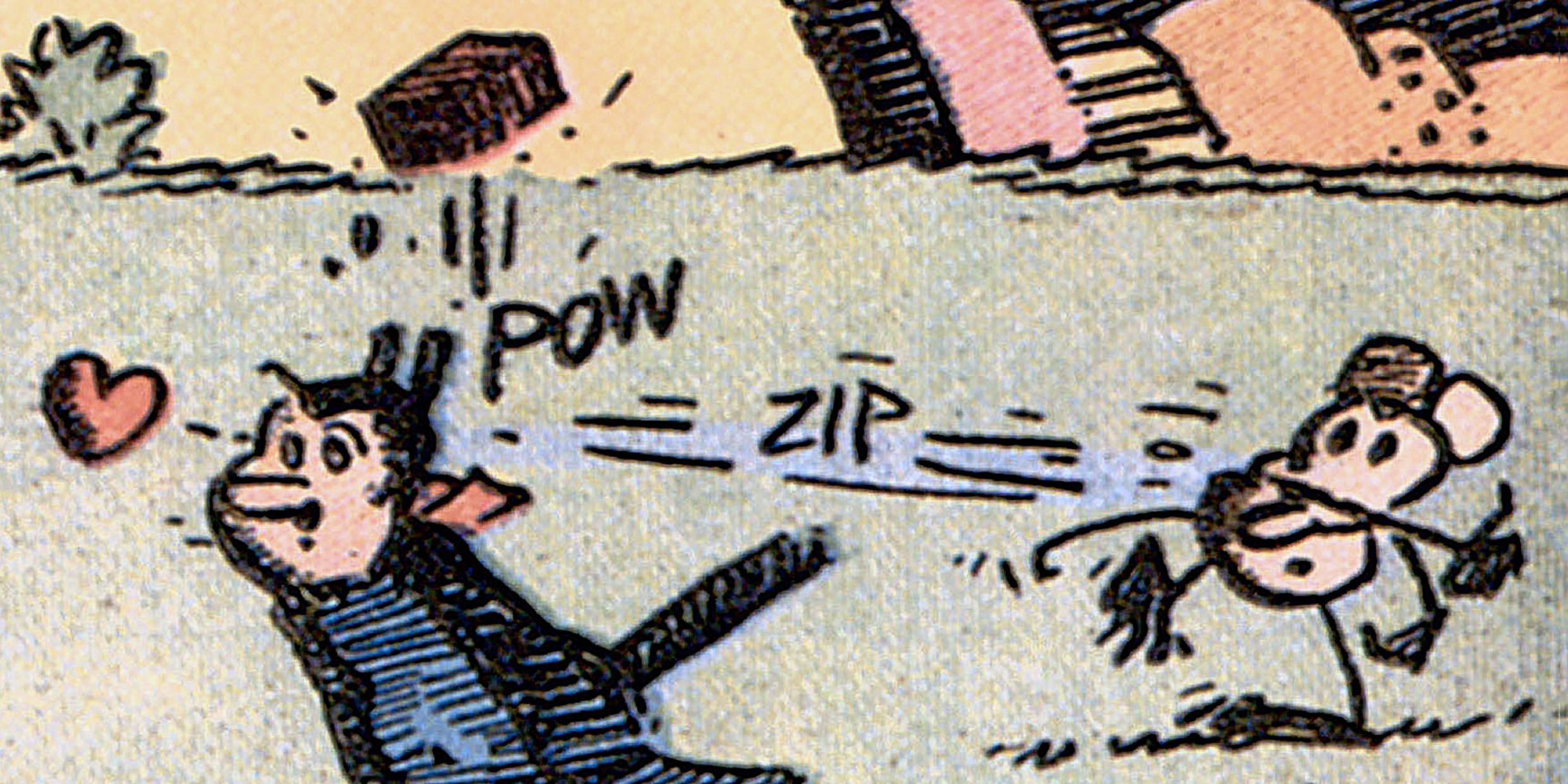

A cat loves a mouse named Ignatz. The mouse’s sole goal in life is to bean the cat with a brick, a villainy welcomed by the cat as a sign of affection, and perhaps it is. A badge-bearing canine, Offissa Pupp, adores the cat and wants the mouse safely behind bars. All of this in a surreal desert place called Coconino County.

Ah, love. The eternal triangle. Or quadrangle — if you include the brick. A web so tangled that even the projectile-hurling rodent unwittingly worships at his target’s shrine. “Loves me, loves me not… No, yetz, no, yetz?” the cat interrogates a daisy. Petals fall as bricks fly.

I’m talking, of course, about Krazy Kat, George Herriman’s artful comic that appeared in American newspapers from 1913 to 1944. No other strip has been so widely admired.

It has been the subject of a novel, a ballet, and, most recently, a dramatization at the Boston Center for the Arts.

The poet e. e. cummings saw Krazy Kat as a commentary on American democracy: a struggle between society (Offissa Pupp) and the individual (Ignatz Mouse) over an ideal of benevolence (Krazy).

Culture critic M. Thomas Inge wrote: “To the world of comic art, George Herriman was its Picasso in visual style and innovation, its Joyce in stretching the limitations of language, and its Beckett in staging the absurdities of life.”

In the current issue of the journal Postmodern Culture, lit-crit scholar Elisabeth Crocker deconstructs the comic in an article called “ ‘To He, I Am For Evva True’: Krazy Kat’s Indeterminate Gender.”

Poor Krazy, forced to bear such ponderous brickbats of criticism. That sweet she/he whose innocent life reduces to “Ignatz!” Zip! Pow! “Ah-h‑h…”

The feline-obsessed critics and scholars have missed the most most important point of all: Krazy Kat as precursor of modern physics.

I’ll not mince words. George Herriman was the Heisenberg of the funnies, the Einstein of Coconino County. He was master of the quantum, the wizard of relativity. His cat, cop, and brick-tossing mouse turned the deterministic world of Newtonian physics upside down.

Krazy was the original Schrödinger’s cat.

It cannot be a coincidence that the first of Ignatz’s bricks were hurled in 1911. That was the year of the first Solvay Congress in Belgium that brought together the architects of the new physics — Planck, DeBroglie, Einstein, and the rest. Already Planck had punctured classical continuity with his notion of quantum jumps, and Einstein had said that space and time were relative to the observer. While the big guns of science were hashing this out in Brussels, Herriman was constructing a comic world on the same principles.

Consider, the problem of Krazy’s gender. Just as light can be sometimes a particle and sometimes a wave in the new physics, so Krazy is sometimes a he-cat and sometimes a she-cat. It depends on who’s doing the observing.

The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle asserts the impossibility of pinning one thing down without another thing going out of focus. And that’s exactly what happens when you read a Krazy Kat strip. Try to pin down Ignatz’s villainy, and his affection for Krazy goes out of focus. Conversely, fix his affection, and his villainy becomes uncertain.

The same for Offissa Pupp. Is he a hero or a kill-joy? The two aspects of Pupp’s character are as inextricably and uncertainly linked as the position and momentum of an electron.

Furdermore…

The plants and rocks of Coconino County transform themselves from frame to frame in quantum jumps.

The sky of Coconino County changes from day to night or night to day depending on who’s doing the looking. Space and time stretch and compress with Einsteinian elasticity.

At the heart of the new physics is the idea that the act of observing affects what we see; that is to say, there is no knowable reality independent of the knower. Does the hurled brick exist unless observed by Offissa Pupp? As Krazy Kat might say, the klub-toting kopp’s act of percepshun frizzes fluxacious reality into an i‑dee fix-ee.

And so furth.

By the time of the sixth Solvay Congress in 1930 — the last that Einstein attended — relativity and quantum physics had triumphed. But Niels Bohr and Einstein continued to debate what it all meant: Is reality dependent upon our participation? Do the laws of nature yield probabilities only? Etc. Etc. Meanwhile, George Herriman had long since answered all these questions in the affirmative.

Coconino County is the ultimate metaphor for the discontinuous, everything’s-relative landscape of 20th century physics — and 20th century life. Krazy Kat is the perfect citizen of such a world, and if we have any sense we’ll try to make ourselves more like her/him.

Take love where we can find it. Look for the best in the bricks to the bean. Be prepared for the improbable.

Zip! Pow! Ah-h‑h…